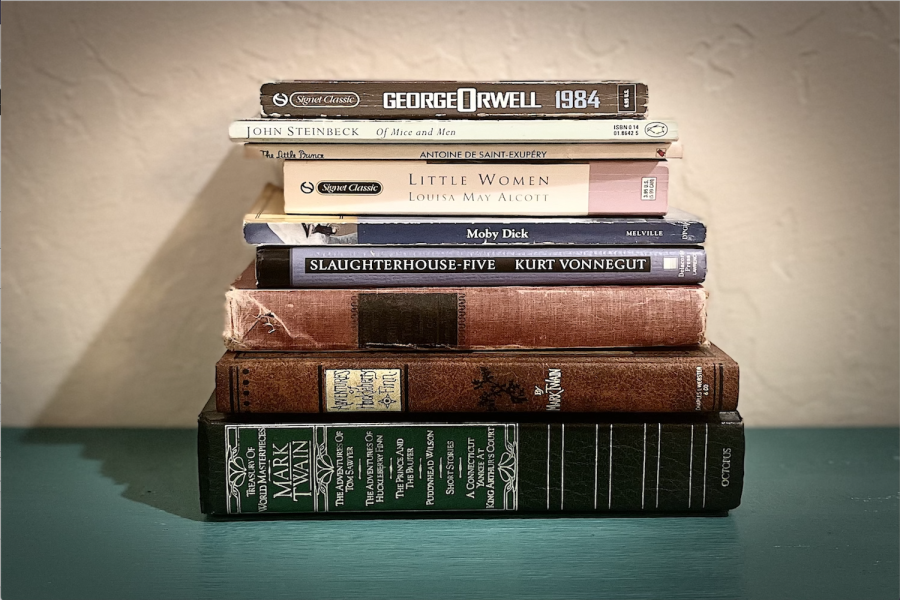

Books are portals to fictional worlds. In flipping through their pages, one can traverse the galaxy with The Little Prince, gaze out to sea alongside Santiago, or enjoy breakfast with the March sisters.

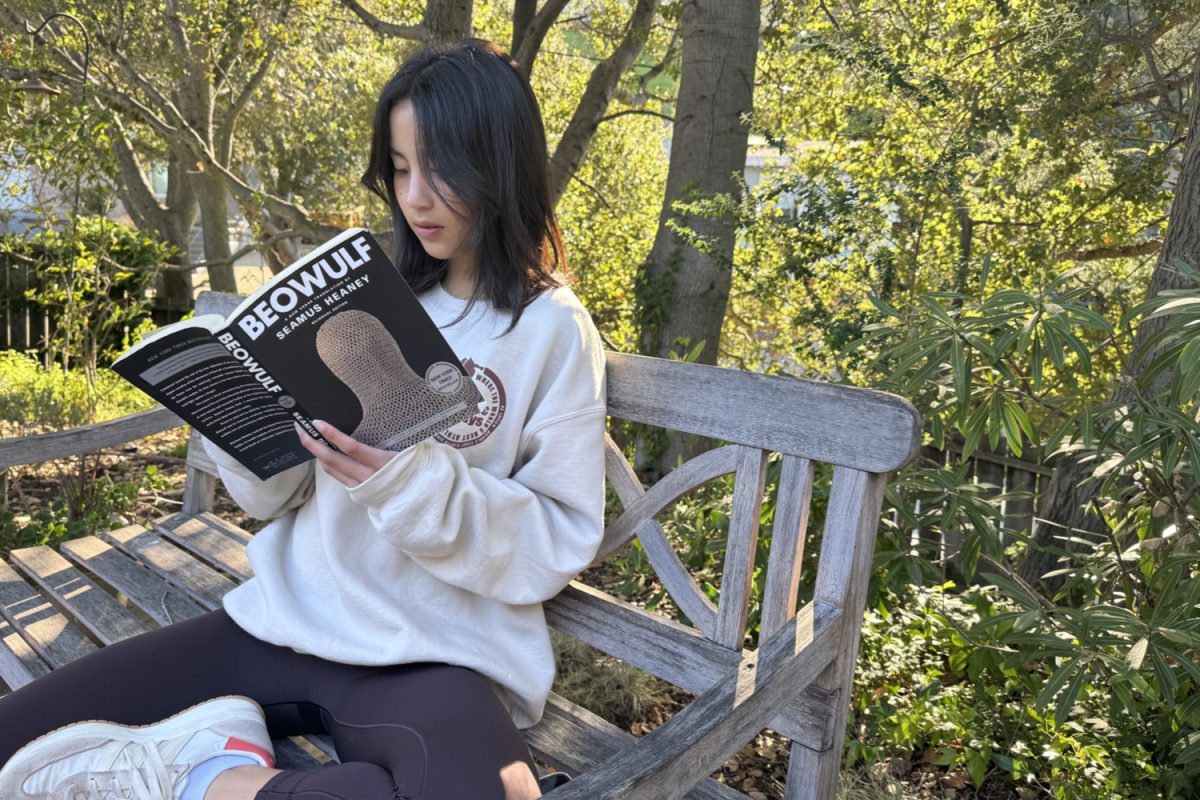

For many, such opportunities for adventure contribute to a love of reading and the unparalleled sense of freedom it offers. A large part of this feeling comes from having the power to choose what to read — to decide which adventure to embark on.

Carlmont students rarely have this choice when it comes to assigned readings. The books we read in English class are decided for us, and our interaction with them is limited to the structure of the curriculum.

This might seem like a logical system. For all intents and purposes, the teacher is in charge of the class, and students can read on their own time if they have different preferences. But upon deeper thought, the idea seems pretty ironic.

At the same time that English courses encourage students to step outside their comfort zone, they cling on to the books taught since the 1960s. English teachers preach the works of Shakespeare, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and other classic writers to a generation that cannot connect to their stories.

The simplest solution to the problem of assigned books being outdated and irrelevant is to introduce new books to the English curriculum, and some high schools across the nation are already seeing this development.

Carlmont is also taking some steps in this direction. Books like “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “The Color of Water” by James McBride, and “A Thousand Splendid Suns” by Khaled Hosseini are now prominent units in Carlmont’s English curriculum.

These stories give students a glimpse of life in the shoes of a character from a different time period, culture, gender, and race. While the effort to educate students on critical social and historical issues is essential, we cannot stop there.

Introducing new books into the curriculum and considering students’ perspectives in the process evidently go hand-in-hand. The former is already being enacted, but giving students a voice is yet to be discussed, even though it is just as pressing.

Incorporating any book into the English curriculum is meaningless if students are disengaged in the material, which often occurs when they cannot connect to the literature.

Studies have shown that students are more engaged in class when they have control over what they are learning. Giving students a say in what books are assigned would offer them this jurisdiction and, in turn, increase engagement in class.

Thus, the next step in the ever-lasting process of updating the English curriculum is to present students with this opportunity to provide their input on assigned readings.

Perhaps it would take the form of a poll listing preapproved books, so students could rank their choices. Or maybe “giving students a voice” could be taken in the literal sense, simply encouraging discussion among teachers and students of what books could be assigned.

One source of hesitation is that it is unreasonable to ask that teachers reconstruct their curricula to suit student-selected texts. While critical to consider, this point does not diminish the overwhelming need for students to have a sense of control over their education by being able to offer their input on required readings.

Considering this alternate perspective only brings us closer to a compromise benefitting both teachers, who would have a more engaged class, and students, who would have more control over their learning and be more likely to enjoy the assigned literature.

Admittedly, students alone do not have the knowledge or resources necessary to formulate the best solution that would ensure our voices are heard in the discussion of what books are assigned to us, but we recognize the pressing need for one and are willing to put in the effort to achieve it.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop Editorial Board and was written by Gabrielle Shore. The Editorial Board voted 10 in agreement and 2 refrained from voting.