Amidst the emergence of the BRICS alliance as a prominent economic counter to American economic hegemony and Western politics, the world feared that China would overtake the U.S. as the subsequent political and economic hegemon. Post-pandemic reports on Chinese population trends and employment suggest a grimmer picture for the nation’s future.

In January of 2023, Chinese officials reported that 2022 marked the first drop in total population in over six decades since the famine of the Great Leap Forward. This event results from decades-long declines in Chinese fertility rates stimulated by the one-child policy and China’s rising abortion and sterilization rates.

Under the one-child policy, introduced in 1979, millions of women were forced to terminate “illegal” pregnancies. The traditional preference for sons led to a mass rise in sex-selective abortions, resulting in the abortion of millions of female fetuses. In the long term, this has contributed to a skewed gender ratio, with the 2021 census revealing that China’s population contained almost 35 million more men than women. This gender imbalance has resulted in social and economic instability in the nation.

Furthermore, despite repealing the one-child policy, China’s fertility rate has dropped to 1.2 births per woman. In context, a nation needs to achieve a replacement level of 2.1 births per woman to maintain a stable, healthy, growing population. This means that for every two people leaving the workforce, at least two people are generated to replace them in the future. Hence, if a nation cannot reach its replacement level for an extended period, its population begins to decline.

While population decline is not uncommon in advanced nations, as exemplified by the United States, Japan, South Korea, Britain, and many Western countries, the Chinese government has seemingly been unable to deal with its rapid decline.

“Neither a shrinking – nor a growing – population represents a crisis in and of itself. Rather, the far more important question is whether state authorities can respond effectively to the challenges such trends pose. There are serious questions as to whether Beijing is up to this task. First, Beijing has been slow to adjust existing policies to respond to China’s rapid aging,” said Carl Minzner, a writer for the Asia Program on the Council of Foreign Relations. “Consider pensions. For well over a decade, Chinese officials have regularly made noises about the need to raise the official retirement age from unsustainably low levels set back in the middle of the 20th century – 55 for women and 60 for men – in light of impending financial pressures. But faced with public opposition from urban elites who benefit most from existing policies, Beijing has repeatedly punted, failing to take meaningful reform.”

Despite a staunch pro-natalist stance, China’s population continues to decline. This, in part, is due to immigration, or the lack thereof. While millions of Chinese citizens emigrate from China in search of economic opportunities, data published by the United Nations in 2020 reported that only 0.1% of the Chinese population comprises of immigrants, and this number is predicted to drop in the future.

“China’s population could shrink approximately 48% between now and the end of the century,” said Simon Powell, Jeffries’ global head of thematic research. “This begs the question of whether China will get old before it gets rich. The simple answer is yes. The population trends suggest that China will continue declining beyond its recovery rate.”

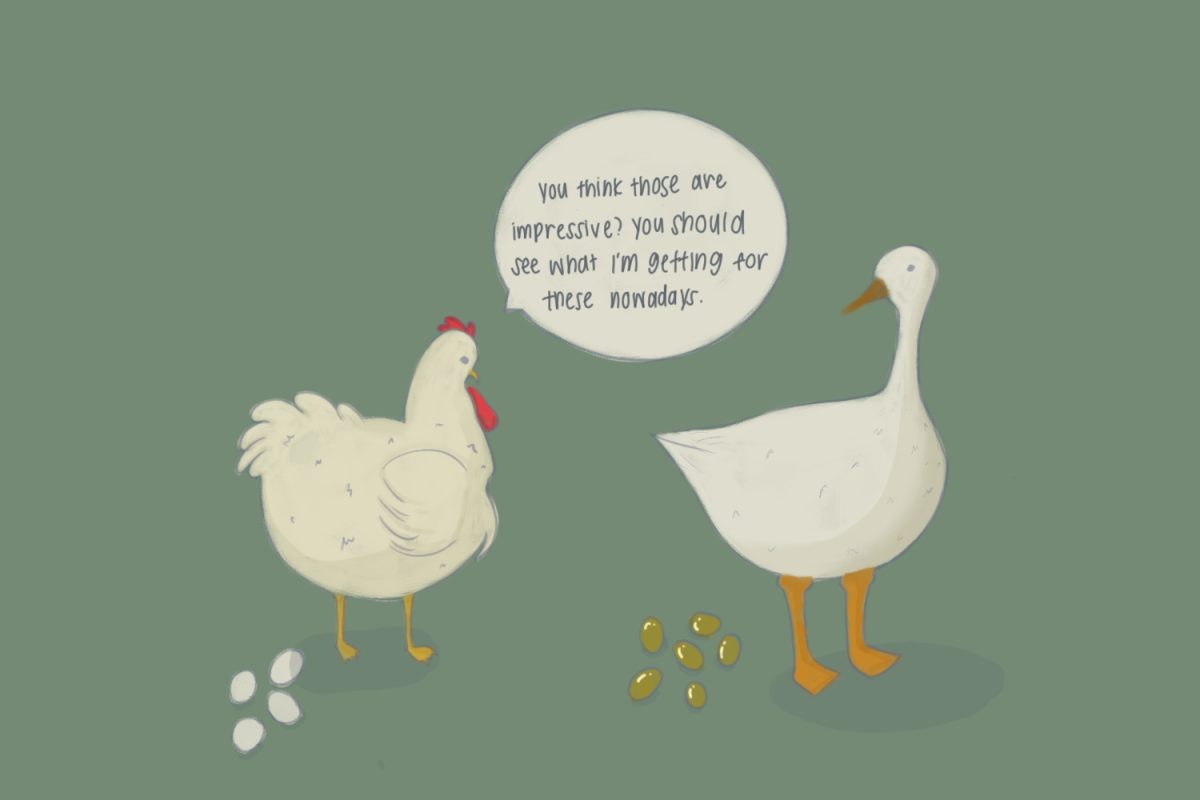

Another issue that is impacting the Chinese economy is youth unemployment. In a now unreleased report published by the Chinese government, the unemployment rate among 16 to 24-year-olds has risen to nearly 22% and is predicted to increase further. China’s youth unemployment rate has doubled in the last four years, a period of economic volatility induced by the “zero-COVID” measures imposed by Beijing that left companies wary of hiring, interrupted education for many students, and made it hard to get the internships that had often led to job offers.

Furthermore, the private sector, which contributes to 80% of the Chinese economy, was hit especially hard during the “zero-COVID” measures pushed by the Chinese government. As a result, many companies, especially in the technology and retail industries, significantly limited or even halted hiring altogether, leading to mass unemployment nationwide. Due to China’s regulatory crackdowns, many industries were slashed by at least 20%.

The decline in population and the post-Covid economic strife have impacted the Chinese housing market significantly. While, on average, a country can attribute approximately 15% of its gross domestic product (GDP) to real estate, housing accounts for over 30% of China’s GDP, according to data published by the Council of Foreign Relations.

Overinvesting could prove disastrous as a significant homebuilder and a prominent investment company have missed payments to their investors in recent weeks. Economic analysts have begun predicting a deterioration of the Chinese housing market. Eagerly anticipated real estate development sites in Chinese megacities have turned into ghost towns because property buyers are pulling their investments out of fear of economic depression.

Additionally, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio just hit a record high, with Chinese debt as a percentage of GDP rising to over 280%, according to data published by the Chinese government.

“It is imperative that the United States takes advantage of China’s rapidly growing domestic crises. While the world perceived 2023 as the end of America’s hegemonic era, China’s economic failures have given the United States an opportunity to step back up to prominence on the world stage,” said Delia Peiko, a senior at Carlmont High School.

Some experts suggest that China’s situation could benefit the U.S. by allowing it to take charge of foreign policy and international economics. U.S. government officials have acknowledged that China’s weakened domestic economy will ease its threat of launching a Taiwan invasion.

Others, however, fear that China’s situation may reflect the coming of more economic hardship at a global level. Analysts suggest that the U.S. faces its own range of economic difficulties, signifying that this decline is not simply an issue that singularly impacts the U.S. or China but a warning for the rest of the world that a more difficult time is yet to come.