Twenty-five years in prison.

Over 12 in solitary confinement.

All starting at the age of 17.

In 1992, Paul Bocanegra, an East San Jose resident, was involved in a drive-by gang shooting in high school. The San Mateo County juvenile court sentenced him to life in prison without parole.

Upon transitioning back into the community in 2017, Bocanegra witnessed children going through the same traumatic experience.

“I thought things had changed,” Bocanegra said. “I saw the same me rewind – the 17-year-old brown kid with a fifth-grade education level could be condemned again, right now, in San Mateo County.”

In the county, the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Commission (JJDPC) is now exploring how it can limit juvenile delinquency.

“The best way to prevent kids from getting in the system in the first place is to make sure that they’re well supported,” said JJDPC commissioner Monroe Labouisse.

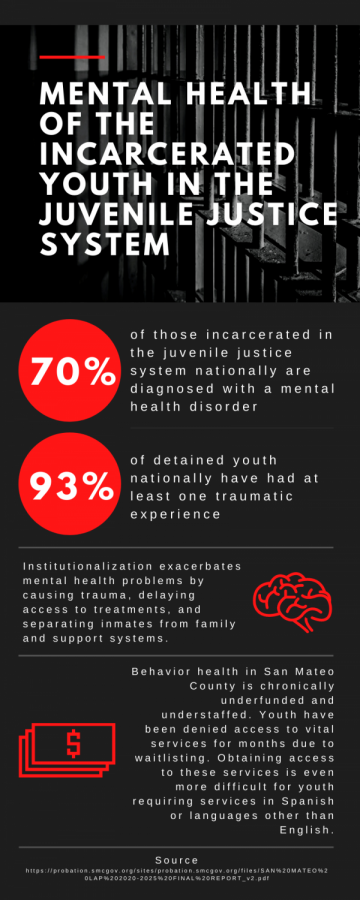

This support is necessary because 70% of youth incarcerated in the U.S. are diagnosed with a mental health disorder, according to the San Mateo County Probation Department and Juvenile Justice Coordinating Council’s Local Action Plan 2020-2025.

To address this issue and improve the state of the San Mateo County juvenile justice system, Labouisse and the JJDPC issued a resolution in October.

“The goal of the resolution is to get a committee of decision-makers for the county who can help turn recommendations to action,” Labouisse said.

These decision-makers include a district attorney, social workers, the probation chief, a superior court judge, and Private Defender’s Office representatives. Labouisse and Bocanegra will also serve as representatives of the public.

The committee’s recommendations range from introducing more supportive mental health programs to altering the cells in which incarcerated youth stay.

“Every kid receives chains and harsh cages as an introduction to the juvenile criminal justice system. Instead, every kid, regardless of what they do, should be able to come for help and get the help they need,” Bocanegra said.

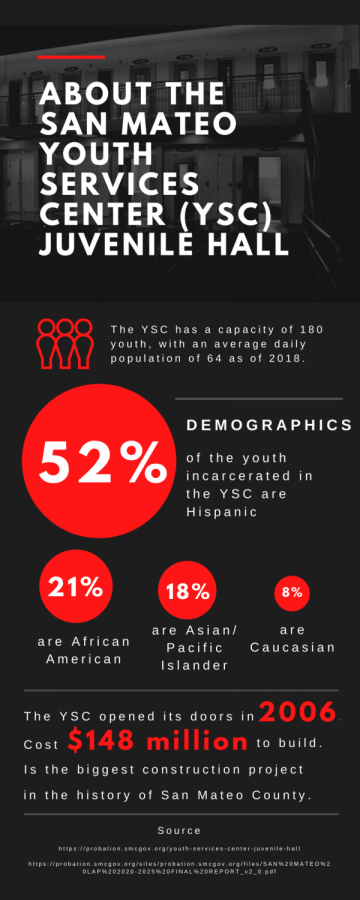

The physical state of the county juvenile hall highlights its close resemblance to adult prison.

“When I started to talk to community members about the punishment model that’s in place, they were extremely disturbed by many of the similarities to adult prison,” Bocanegra said.

The traumatic backgrounds of many kids in the juvenile justice system support the initiatives for a less harsh juvenile hall.

“The children are already emotionally scarred and have survived a lot of trauma,” said Debora Telleria, the JJDPC co-chair. “How do we help that? How do we address the trauma rather than punish the action?”

The committee created in October will discuss these questions, but they’ll also be taking steps to initiate meaningful action.

“What I want to do, rather than punish a kid when they do something wrong, is find out why,” Telleria said. “There are different reasons people do things, and understanding the root causes of why someone committed a crime showcases their needs.”

These new approaches intend to ease the process of juvenile incarceration, especially for the youth of color.

“These kids come predominantly from low-income families and are almost entirely people of color,” Labouisse said.

The disproportionate percentage of youth of color in juvenile hall and the history of abuse in the juvenile justice system motivate people like Bocanegra to work towards bettering the lives of incarcerated youth.

“We are looking at kids not as kids anymore. We are quick to see these kids as adults,” Bocanegra said. “Youth can change.”