A new tool, Nightshade, allows artists to tweak their art’s pixels before sharing it online. These invisible changes can break Artificial Intelligence (AI) generation models if the art is used in their training without permission, causing unpredictable results, according to a report on the tool.

Nightshade allows artists to fight back against AI companies that do not respect artists’ work. The tool effectively embeds a “poison pill” within images used in training data, having the potential to damage future iterations of image-generating AI models, such as DALL-E and Midjourney.

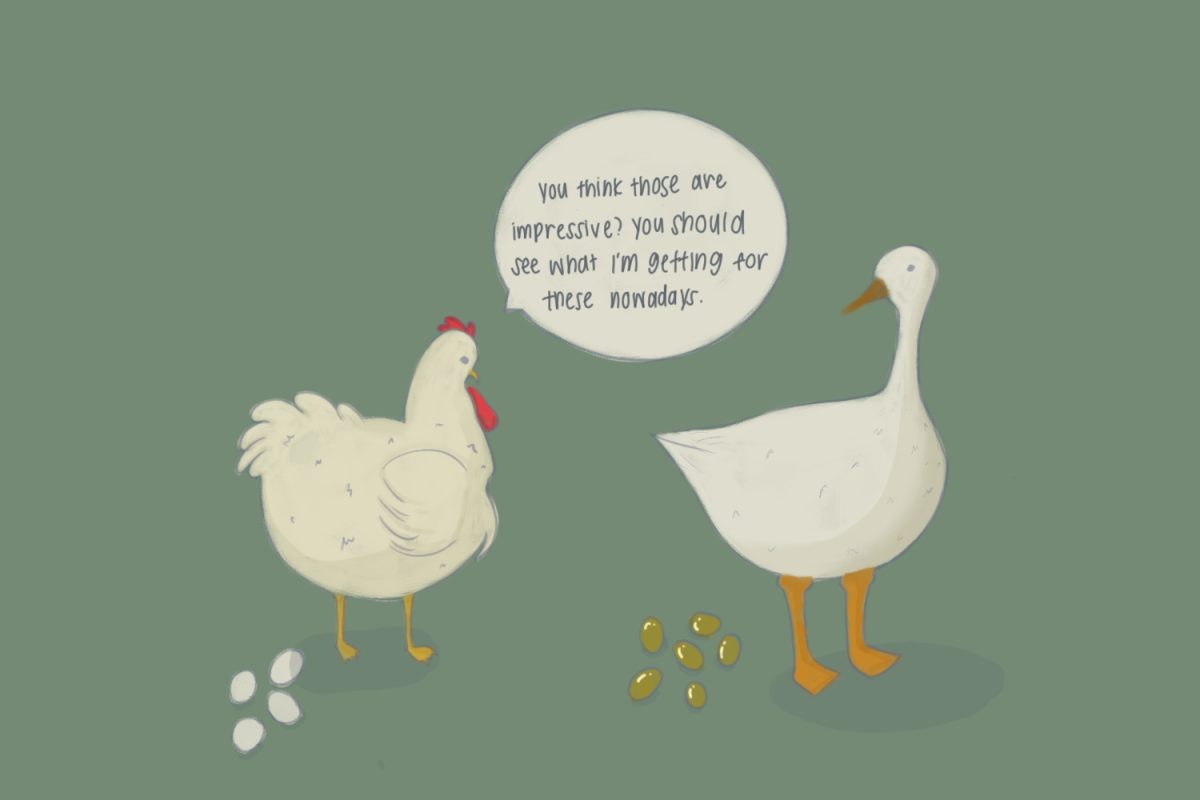

Artwork utilizing Nightshade can confuse the model and alter its ability to associate specific text labels with images.

Generative AI models are often trained on a vast amount of data, including copyrighted images found on the Internet. If artists don’t want their work to be scraped by AI models, they can use Nightshade to allow for poisoned samples to make their way into the model’s data set, causing it to malfunction.

Ben Zhao, a computer science professor at the University of Chicago, led the team that created Nightshade.

“Up until now, content creators have had zero tools at their disposal to push back against those who don’t respect copyright. Those who want to just take anything online and claim ownership just because they have access. Nightshade is designed to push back,” Zhao said.

Nightshade thoroughly misleads AI models, making them prone to mistaking objects and scenes depicted in content. For example, during its testing, it turned dog images into data that looked like cats to AI models. With just 100 altered samples, the AI consistently generated cats instead of dogs.

Because the researchers cannot determine which websites and when models scrape training data, most poison samples released may go unnoticed. Thus, enhancing potency becomes crucial. As demonstrated by this data, the attack is powerful enough to succeed even if only a small portion of poison samples enters the training pipeline.

While the changes made to art by Nightshade may be undetectable by the human eye, in the model’s understanding, the image possesses traits of both the original and the manipulated concept.

Eliminating the poisoned data is challenging, meaning tech companies have to painstakingly locate and delete each corrupted sample individually.

Additionally, generative AI models link terms together, making the poison’s spread more effective. For instance, Nightshade doesn’t just affect the word “apple” but also related concepts like “fruit,” “orchard,” and “juice.”

The poison attack extends to loosely connected images as well. For instance, if a corrupted image is used for the prompt “fantasy art,” related prompts like “unicorn” and “castle” would also be influenced, making prompt replacement ineffective.

Nightshade’s attacks succeed when poisoning multiple concepts within a single prompt, and these effects are cumulative. Moreover, targeting various prompts on a single model can corrupt general features, causing the model’s image generation function to collapse.

Nightshade expands on Zhao’s team’s previous work with Glaze, a tool designed to confuse AI by altering digital artwork styles. While Glaze focuses on changing the artwork’s style, Nightshade takes it a step further by corrupting the training data.

Although the new tool harms AI models, Zhao emphasizes that he wouldn’t characterize it as a step back for AI image generation.

“This is not a race to some destination. This is effectively a struggle. One might even call it a battle between AI model trainers who feel like they can take any content online and make it their own and creators who actually respect the idea of content ownership and copyright. Nightshade is designed to be a tool to even the battlefield,” Zhao said.

According to Joseph Espinosa, a visual arts teacher at Carlmont, it’s important to clarify that AI in art is not necessarily a bad thing.

“AI has gotten a lot of bad rap, but I think it’s a beneficial tool. Many artists use AI-generated art as references and inspiration for their own work. I’ve even considered using AI in class for this reason,” Espinosa said. “Where people have an obvious problem with AI is that the AI companies are making money by sourcing the material that they use to gather their imagery illegally.”

Companies often do this to benefit financially from using artists’ content in this way.

“These companies have it in their best interest to steal other people’s art because everybody else is doing it. In order for them to be competitive with each other as AI companies, they’ve got to do whatever they possibly can to be successful. Even if it’s unethical,” Espinosa said.

Although many companies with image synthesis models disregard ethics, notable exceptions include Adobe.

“Adobe presents an interesting case in the generative AI space, claiming to exclusively utilize their proprietary data to train their AI models. This approach potentially sets a precedent for ethical data usage, where the artists whose works contribute to the AI’s learning process are recognized and compensated, though the specifics of the compensation remain a topic for further examination,” said Gil Appel, an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the George Washington University School of Business who has conducted research on intellectual property as it relates to AI generation.

Adobe’s practice aligns with the responsible and transparent data-sourcing strategies discussed in the broader context of AI development and copyright issues, offering a model that others in the industry might follow.

Some AI companies that have developed generative text-to-image models, such as Stability AI and OpenAI, have offered to let artists opt out of having their images used in future training data, according to Technology Review. However, these policies still leave power in the hands of tech companies and indicate that all content accessible online is automatically opted in, effectively disregarding artists’ right to choose.

“What’s really exciting about Nightshade is the potential shift it represents in the power dynamics between individual creators and tech giants. Nightshade could be a game-changer, nudging companies to be more mindful and perhaps encouraging a trend where asking for consent becomes the norm, not the exception,” Appel said.

Zhao agrees, believing that AI companies should take a simple course of action.

“They should do what they should have done in the first place, which is to respect ownership of content and train on things they have licenses for,” Zhao said. “They should just behave like everyone else and pay for their right to access it.”

With this initial success of Nightshade as a data poisoning tool, Zhao acknowledges that there is a risk that individuals could abuse the tool for malicious uses. However, attackers would need thousands of poisoned samples to inflict real damage on more powerful models that use billions of data samples to train.

Regardless, Nightshade has proved to be useful in the way it was intended.

As stated in the UChicago researchers’ report, moving forward, poison attacks could encourage model trainers and content owners to consider negotiating the licensed acquisition of training data for upcoming models.

“This tool isn’t just a technical fix. It’s a statement about valuing the artist, and it could lead to a future where creativity and technology go hand in hand in a more respectful and legally sound way,” Appel said.