Upon opening her inbox, she sees an unread email with the subject title “Internship Application Update.” She clicks the email expecting a rejection letter. To her surprise, the message read, “Congratulations! We are extremely excited to offer you the internship position….”

Instinctively, thoughts of her acceptance letter being a direct consequence of a lack of applicants, rather than her merit or skill, blare through her head. She concludes that the result was pure luck and continues to question if she deserved the position.

First identified in 1978 by Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes, imposter syndrome is when an individual creates a false narrative and believes that they are undeserving of being accepted into a particular environment. Due to this, they fear that surrounding individuals will notice their lack of belonging.

Shelly Bustamante, the Students Offering Support coordinator at Carlmont, mentions that when one is experiencing imposter syndrome, they may not be conscious of it. One indication of imposter syndrome is that individuals will invalidate their merit through illegitimate reasoning instead of accepting and acknowledging their achievements.

“It’s difficult for them to accept compliments. They are always thinking, ‘I am not worthy, that it’s luck, it’s nothing to do with their merit.’ The emotions could be a sense of stress, helplessness, sadness, and fear; you know, fear of being found out that you’re not worthy,” Bustamante said.

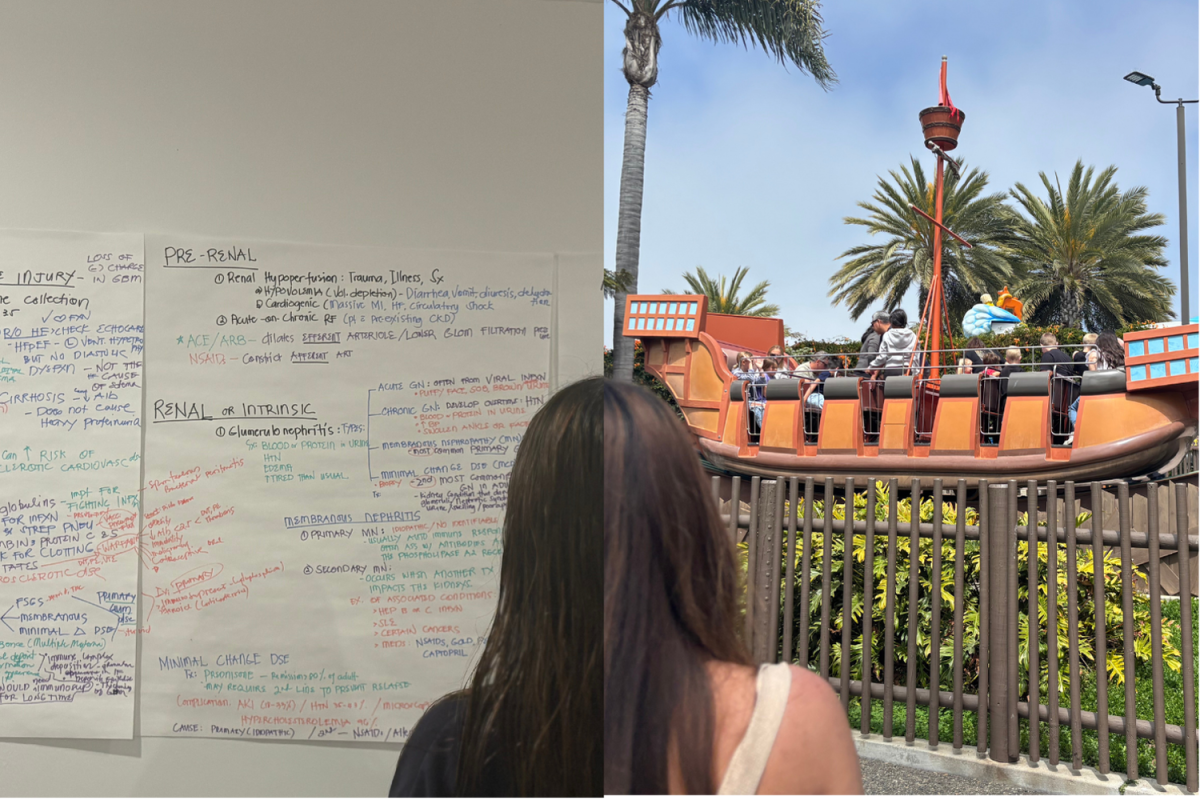

Jeslyn Chun, a senior at Carlmont, notices that she experiences some of these thoughts while in the classroom setting. Upon reflecting on a reason for these emotions to be invoked, she believes it correlates with the competitive atmosphere.

“When I receive a bad grade on a test or an assignment and then hear other people around me getting better grades, I feel like whatever I do in school is just never enough for me to get into college and stuff. I constantly feel like the other students around me are more deserving as they have more competitive stats and whatnot,” Chun said.

Chun believes that the competitive atmosphere cumulated with her childhood experiences contributes to these thoughts. At a young age, Chun excelled in school, and everything she learned came with ease causing her to set extremely high standards for herself then, which have continued to today.

“When I was younger, things came easy to me, so then when I got into high school and middle school, I was like okay, this would be easy, but then, you know, it’s not. This led to my expectations for myself to be super high, so whenever I get a bad grade or something in that general vicinity, I tend to beat myself up about it,” Chun said.

Chun would be correct regarding her childhood playing a pivotal role in her expectations. Dr. David Gard, a clinical psychologist and professor at San Francisco State University, believes that human beings are innately motivated to adapt to the expectations around them as a child, meaning many of the experiences from one’s childhood will be embedded into their habits. He also mentions that the need to stay close to others and societal categories may also contribute to the development of imposter syndrome.

“When someone starts to feel that if they do well in something, and notice people moving away from them, that can also create imposter syndrome and most of the time the person is unaware of it. When this happens, some may develop a narrative that they aren’t good at something as a means of feeling safer,” Gard said. “Imposter syndrome can also be related to cases that are essentially racism, sexism, homophobia. All those things can play out outside of the person’s awareness, where they believe they’re an imposter in that group because of the stereotypes in the environment. However, that has nothing to do with their natural talents or abilities. An example may be women in STEM.”

The adverse effects of imposter syndrome are vast. Gard claims that one of the major effects is worsened performance during activities due to the increased feeling of needing to prove themselves.

“The person belongs there, but they don’t think they do, and sometimes that can actually mean that people will ironically play out the imposter syndrome such that they do put more poorly. They’re anxious about their performance, which decreases their level of how they’re doing relative to their peers, and then it confirms the fears,” Gard said. “For example, you’re a really good clarinet player and you get accepted into this band, that’s good. Imposter syndrome gets activated, the person feels like an imposter, and then they end up doing worse. They then say ‘oh, it seems because I was an imposter.'”

Bustamante has also witnessed other detrimental effects correlated with imposter syndrome, including anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse.

“It can definitely cause anxiety which can go hand in hand with depression. I have a friend, who is a therapist, and she deals with a lot of these individuals from highly respected fields, who deal with substance abuse and, you know, the negative self-talk,” Bustamante said.

More times than not, imposter syndrome disproportionately affects higher achieving individuals. This is because higher-achieving individuals tend to set close to perfect or perfect expectations for themselves.

“I think when people are really high achieving, they often do really well, but nobody’s perfect, and they make mistakes. The perfectionism ends up undermining them, and they think, ‘if I’m not the best, then I must be the worst,'” Gard said.

According to Bustamante, a lack of balance decreases how an individual views their self-worth. She has noticed, at Carlmont specifically, that the academically competitive environment contributes to many students experiencing imposter syndrome.

“When the focus is on one thing, and you put all your eggs in that basket, like when a kid’s worth is only their academics, it manifests into them believing they need to take all these AP classes in order to be worthy. There isn’t any balance, and it’s all about achieving, but not retaining or appreciating the achievement because it’s just more of a thing that has to be done and not a sense of accomplishment,” Bustamante said.

Since many individuals are unaware they are suffering from imposter syndrome at the moment, Gard recommends that individuals collect data and step outside of their comfort zones. Collecting data to prove certain negative perceptions of themselves will allow individuals to comprehensively analyze if their negative affirmations are rooted in truth or reveal if they are suffering from imposter syndrome.

“The suggestions that most people make around getting rid of imposter syndrome are very similar to the ones that we make about anxiety, which is to move towards the things that make you anxious, not away. So, if you feel like you’re the worst clarinet player, gather data, perform, put yourself out there, not one time, not two times, like 15 times. Look at the data and see where you fall relative to your peers,” Gard said. “Oftentimes, people don’t have any data for it; it’s sort of just like a feeling. That’s a good red flag that indicates it’s not real.”