This week, we’re going to take a look at a popular game: Carcassonne, designed by Klaus-Jürgen Wrede and currently published by Z-Man Games. Up to five players can play Carcassonne, and games take about 30 minutes to play. However, Carcassonne appeals to more people because it is a gateway level game, slightly more complicated than classic games like Monopoly and Clue. Throughout the game, players will draw tiles and place them to build the city of Carcassonne. They’ll score points by completing roads, cities, and monasteries with their people in them. Without further ado, let’s look at how this gateway level game gets people into the hobby and its legacy in board game history.

How to Play

Each player will get meeples, wooden pieces shaped like people. One of your meeples goes on the score track, and you’ll keep the rest in your reserve to play the game. You’ll also place the starting tile in the center of the table. The rest of the tiles form a few face-down stacks.

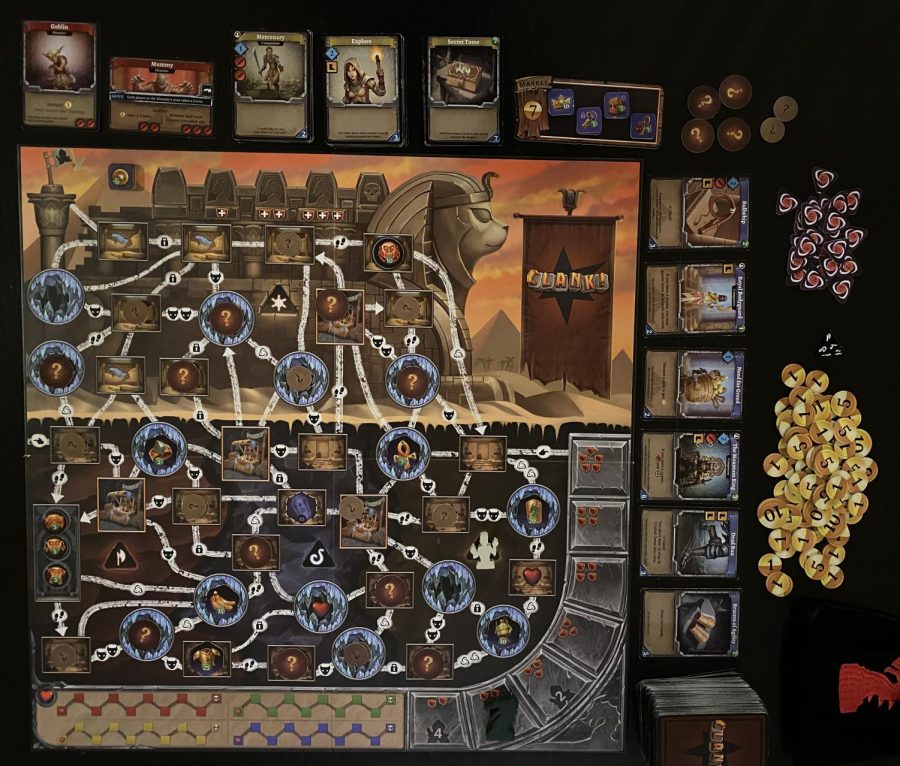

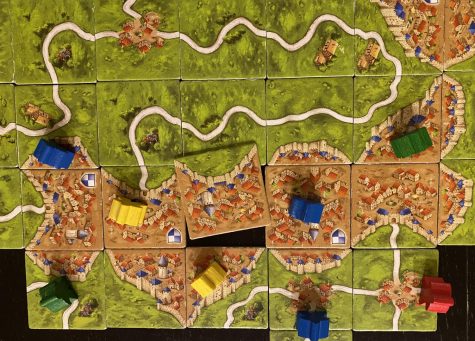

On your turn, you’ll pick a tile from a face-down stack and add it to the city of Carcassonne. The square tiles can go in any orientation but must touch at least one other tile. All of the sides that will touch other tiles must match. Roads must connect to roads, cities to cities, and fields to fields.

After placing your tile, you may place a meeple from your reserve on the tile you placed. You may place a meeple on a road, city, or monastery as long as no other meeple is already on that feature.

Once you place a meeple or choose not to, you’ll check if you completed any features. If so, the player who has the most meeples on that feature will score points for it. Then, players return all their meeples from that feature to their reserve.

You complete a road when both sides of the road hit another feature like a city or the road loops back to itself. The players who have the most meeples on that road will score one point per tile that road is on.

A city is complete when the wall bordering the city is complete, and there are no missing tiles in the city. Regardless of who placed the tile, the players who control the city get two points per tile that make up that city. They also will get two points per shield icon in that city.

Monasteries will score points when eight tiles surround it. The player whose meeple is on the monastery gets nine points. Unlike roads and cities, other tiles cannot expand monasteries, so only one player can place a meeple on each one.

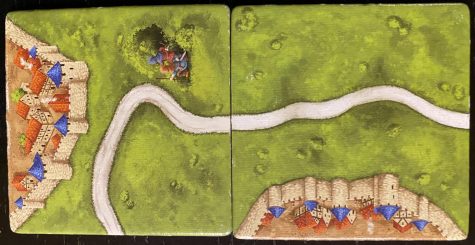

Since you cannot place your meeple on a feature that already has a meeple, you may be wondering how there could ever be more than one meeple when scoring a feature. At first, each road or city is a separate, small feature, but they could connect, as shown in the photo on the right.

When someone places the last tile, the game ends. Players will score one point for each tile depicting a road they control, one point for each tile showing a city they control, one point per shield in a city they control, and up to eight points per monastery they occupy based on how many tiles surround it. The player who has the most points is the winner.

Final Thoughts

Carcassonne is an important game because it leaves a strong legacy in many ways. When we look at the components for the game, the most colorful pieces are the meeples. Carcassonne was the first big game to use meeples. They have become a huge part of so many other games such as Stone Age and Wayfinders, to name a few. The tiles also have good artwork and resemble the city of Carcassonne extraordinarily well.

Carcassonne also leaves behind a legacy in the tile placement game genre. Its tile placement mechanism is different from other games of similar complexity. The classics like Monopoly and Clue have players roll dice, move, and maybe do something based on their roll, but Carcassonne doesn’t have dice. It requires more thinking because you have to look at a tile and see where it fits.

Furthermore, Carcassonne does a great job showing a variety in the strategic depth of board games. There are more than just light, classic games and mind-bending, complex games; there’s a whole range of mid-weight games. This game is definitely on the lower side of this spectrum, making it one of the top games for introducing people to the board game hobby.

Carcassonne is an easy game to learn and teach others. When you first start to play it, it’s a lot of fun. It’s exciting to see what tile you’re going to get; it’s interesting to see the different ways you could place that tile on the board. It’s also fun when you notice you are getting better at the game each time you play. At first, you’re just trying to figure out where you can put your tile, then you find some tricks to score more points, and lastly, you learn some advanced maneuvers to share points that your opponents worked so hard to get.

Carcassonne was monumental in the history of board games, not because the tile placement mechanism was new, but because it introduced a general audience to all sorts of games. Carcassonne has a tile placement mechanism, but if you look at games slightly further along the complexity spectrum, you’ll see drafting, deck-building, worker placement, and other mechanisms that people never imagined in board games. This game is one of the first gateway games to be successful enough to bridge the gap between well-known games and more strategic games.

Like most gateway games, I lost interest in Carcassonne after playing it enough times. I played it a lot at first but then decided that it wasn’t strategic enough. Even then, Carcassonne did its job as a gateway game, transitioning me to games with more strategy. Now Carcassonne does have tons of expansions and variants that add new, special tiles. While that’s interesting, more tiles mainly increase the game length, so it doesn’t solve the strategic problems.

The main issue is that you always draw one tile and have to place it. Even though you can choose where to put that tile, you can’t decide what’s on the tile, so there is a high amount of luck involved. One popular variant is to hold three tiles in hand at a time. I tried it once but found that the issue still prevailed; your hand would just get clogged each time you drew a tile you didn’t like. You eventually had to play all your tiles anyway, so it didn’t make a huge difference.

There are many gateway games available now, and some have figured out tricks to mitigate the problem of their game getting stale. One common example is how Catan added expansions that increased the amount of strategy in the game. Ticket to Ride is a fantastic gateway game because it is one that I never have issues playing again. I play it less now than I did in the past, but it’s a gateway game that I would never complain about being lucky or having too little strategy.

Ultimately, my verdict is that you should invest in Carcassonne regardless of whether you like board games or not. If you do like games, this game will help you discover how much more there is to board gaming through its unique mechanism and what it represents in board gaming history. If you don’t tend to enjoy playing games, you should try Carcassonne; it might change your mind. The reason you haven’t liked games may be bad memories of games with too much luck and no strategy. If that’s you, I’ll tell you that Carcassonne is a different kind of game; it gives players control over their game while remaining fun and exciting.

The only group of people I would not recommend this game to is people who have already played gateway games and moved on to more strategic games. They will find that Carcassonne gets boring much quicker than others and not a worthwhile buy. While it’s not the best game for a long-term investment, the $25-40 you pay for the game is worth it. It shows you modern games as it takes you through the keyhole, unlocking a world that many people don’t know exists. With the lack of long term replayability is substantial criticism, Carcassonne provides a fun experience for everyone, and its essential role in board gaming gives it a higher ranking at 7.5 out of 10.

[star rating=”3.75″]