Convert your small town into a thriving city. Build residential, civic, industrial, and commercial industries to get a larger population than all of the neighboring boroughs. This is the goal of the board game Suburbia, published by Bezier Games and designed by Ted Alspach.

How to Play

Suburbia is an economic city building game. Each round, players get to place a tile into their borough. At first, they want to build up income so that they can afford more expensive tiles. However, as the game progresses, players will try to increase their reputation to get a higher population.

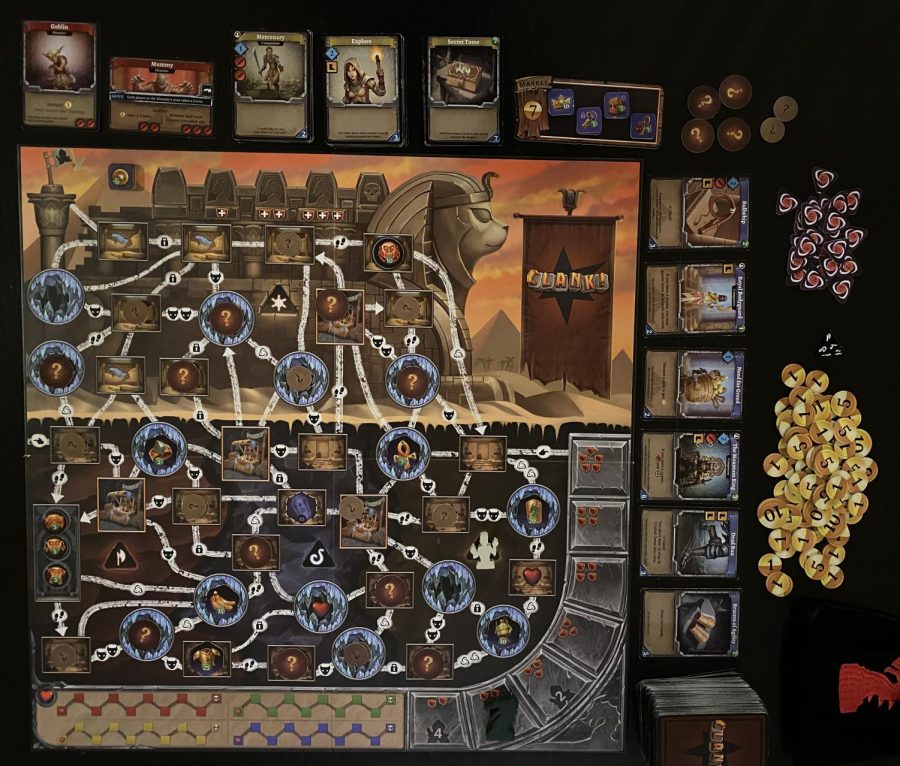

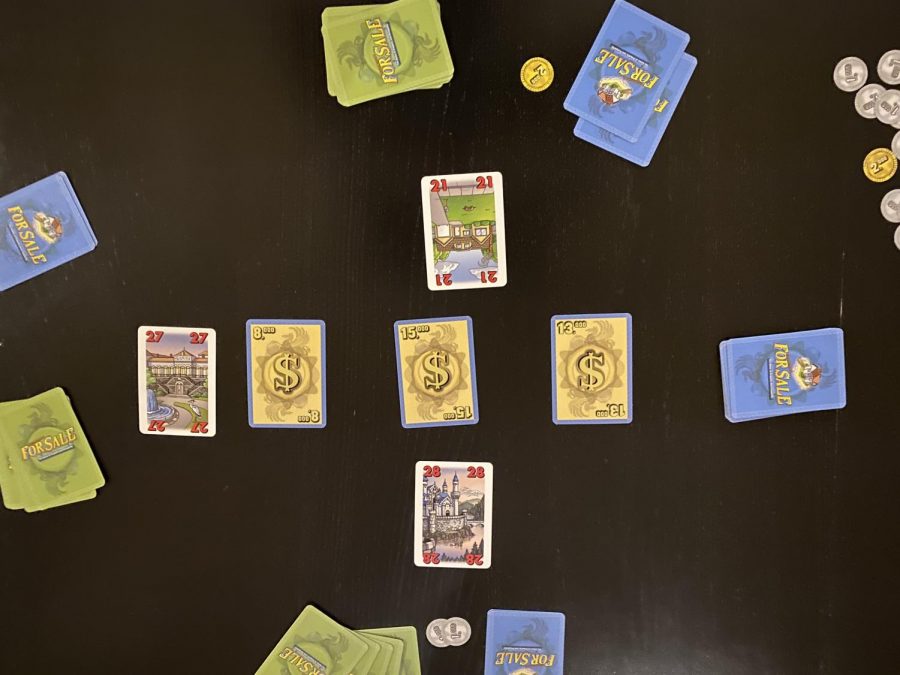

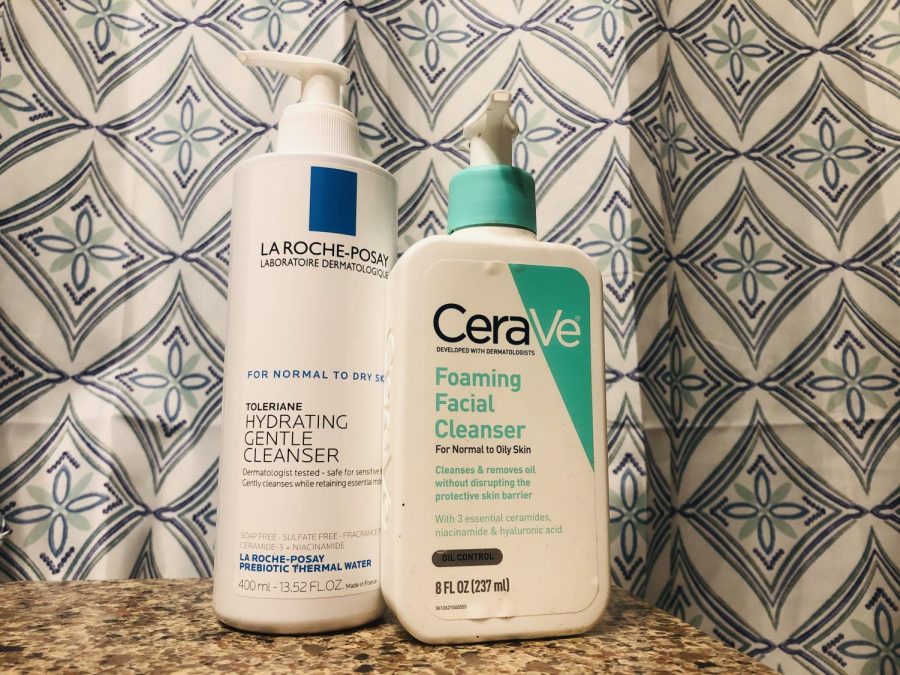

The picture below shows the setup of the game. Each player gets an area where they will build their city with the given resources. At the start of the game, each player is given three tiles; these tiles give the player a starting income of $0, a starting reputation of one, and a starting population of two. Player boards separate each player’s borough, mark income, and reputation. Furthermore, each player starts with $15 and three investment tokens.

The player boards and main boards make the game easier to setup and play.

The communal area, shown to the right of the player boards in the photo, consists of three boards and the scoring track. The first board is for the money, the middle one is home to basic tiles and public goals, and the last board is where the tiles are stacked. The tiles are divided into groups “A,” “B,” and “C.” Each letter has different building tiles, and the number of buildings in each stack change with different player counts. The first seven buildings from the “A” stack are placed face up in the Real Estate Market below the middle board.

Before the game begins, each player looks at two private goals and selects one to keep. Goals give players something to aim for. For instance, a goal might award the player with the fewest green tiles or the highest income at the end of the game. Anyone can win public goals, but the private goals can only be won by the player who selects it. The goals will affect the player’s strategies.

Now that the setup is complete, players take turns either placing a building tile or investing in a building.

Placing a building tile

Most turns, players will buy a building from the Real Estate Market. To do this, the player must pay the cost of the tile plus the cost printed above the tile. The player then places the tile in their borough adjacent to at least one other tile.

Players will now have to make adjustments because of this tile. The player must consider the effects from this tile, all adjacent tiles, other tiles in their borough, and tiles in opponent’s boroughs. These effects include changing income, reputation, money, and population.

The player has placed the parking lot. They get +1 income because of the effect in the upper right corner. The parking lot makes +3 income for having three blue or gray tiles adjacent to it. The postal service makes +1 income for adding another blue tile. The community park makes +1 reputation for the adjacent blue tile. The lake makes $2 for a new adjacent blue tile.

Players may not always like the tiles in the market row. However, the effect they are looking for is probably on a basic tile. To buy a basic tile, the player chooses one of the tiles and pays the cost of the tile. After placing the tile and resolving all the effects of it, the player must remove a tile from the Real Estate Market. They only have to pay the cost printed above the tile when removing it.

The last kind of tile a player can place is a lake. To place a lake, the player chooses a tile in the market row. They only pay the cost printed above the tile and then turn it over. The backside of each tile shows a lake and its abilities. Lakes cost $0, which is why the player only pays the cost printed above the tile they selected. The purpose of lakes is to earn cash. Lakes provide the player with money for each adjacent tile.

Invest in a building

Players do not have to place a new tile each turn. Instead, they can invest in a building they already have. The player places an investment token on any tile that doesn’t already have one on it and pays the cost of the tile they invested in. Investment markers double the effects of the tile they are placed on. The tile itself still only counts as one tile, so it does not affect adjacent tiles or tiles elsewhere.

Using the photo above, if a player placed an investment marker on the parking lot, they pay $12. They get +1 income for the tile itself and +3 income for the adjacent blue and gray tiles. The parking lot will make +2 income for any future adjacent blue or gray tiles. Notice that the abilities of the postal service, community park, and lake were not triggered because the parking lot is still only one blue tile.

After placing the token and making any adjustments, the player must remove a tile from the market row by paying the cost printed above it.

Once players do one of these things, the rest of their turn is simple. The player gets money equal to their income. Next, the player moves forward one space on the scoring track for each reputation they have. Anytime a player crosses a red line on the scoring track, they lose one income and one reputation.

Before the next player takes their turn, all tiles in the Real Estate Market slide over toward the $0 side. The next tile from the stack appears under the $10 sign.

When the One More Round tile appears, it means that the current round is finished, and then all players get one more turn. The game ends, and players conduct final scoring, ignoring red lines. Players add up points from public and private goals. Every $5 the player has leftover is also worth one point. The player with the most points is the winner.

Final Thoughts

Suburbia is an award-winning game. It is popular in the board gaming world, and lots of people like it.

However, I don’t like it. Suburbia offers a lot of exciting mechanisms and choices but is definitely overrated.

We’ll start with the artwork and components. The artwork is excellent all-around from the box to the building tiles. I like how the tiles have lakes on the backsides, so you can just turn them over when building a lake instead of having to take a tile from somewhere else. The building tiles are easy to read, and the player pieces work well. I like that they provided a marker with a circle or square bottom based on whether the track had circular or square spaces.

The player boards that mark income and reputation can also be flipped around, so the player builds from the bottom up. The boards in the communal area are not blank. They tell you how many buildings to place in each stack, how many public goals to use, and the additional cost for the tiles below that spot on the Real Estate market. All of these things make the game easier to play.

Some buildings have a building type marked on the right part of the tile. Some tiles have interaction based on these types. It’s a thematic concept to make tiles less valuable as future tiles of the same type appear.

The meat of the game is the building tile selection and placement of the turn. Selecting buildings has the right amount of competition. The tiles that nobody picks move toward the $0 side and become cheaper. New buildings, whether they are useful to you or not, start at the most expensive end of the market row. The luck in having a good building show up on your turn is mitigated because getting that building will cost you a $10 premium, and money is always a tight resource.

The building placement is also a factor. As you will quickly learn, utilizing adjacencies and the conditional effects of the buildings is essential to scoring points. However, the tile placement is not a significant strategic point in the game because it is usually obvious where you want to place a building tile. The only time you will deviate from the ideal placement is if you are trying to get a particular goal or a specific tile.

Overall, the game provides a lot of other options when you don’t like any of the tiles in the market row. If you need some money, you can build a lake. If you need income, there’s a basic tile for that. If you, remove a building from the market row, you can preserve the game length and allow players to block each other.

The other option players have is to place an investment token. Investment tokens are my favorite part of the game because it can yield tons of points if you plan correctly. You will usually use the tokens differently each game because the tile you want to invest in changes in each game. Paying the cost of the tile you are investing in balances the abilities of the tiles, and removing a tile from the market row once again keeps the game length the same. It’s one of the few moves in the game that allows you to benefit and block another player in the same turn. Three of these tokens will enable you to do what you want to do without going overboard.

At the end of your turn, you receive money based on your income, population, and reputation. The idea of building up an engine to get money and points each turn is a novel idea. However, keep in mind that passing a red line lowers your income and reputation one step each. Because of this, players must follow a single strategy to win the game.

This strategy is to focus on your income first. When you can afford a decent tile most rounds, you can start to focus on increasing your reputation and your population.

If you try to increase your reputation instead of income, you’ll find yourself in a trap where you keep hitting red lines. If you do it long enough, you won’t have a high enough income to afford any tiles. The income strategy may seem obvious to some, but it is the only strategy. It is a huge flaw that the game can only be played that way. I feel like it is notorious for a game to allow players to do something that they think is useful, like build up their reputation to get points, but instead it hurts them for it since you end up hitting too many red lines to afford any tiles.

More bad news is that the game has a steep learning curve. It often takes a few disastrous games to figure out how to play with that strategy.

The good news is that there are different ways to play the same strategy. Each player will have to decide a turning point when they start to get more reputation and population. However, they may have to take a turn to increase their income again if they find themselves short of money after crossing a few red lines. The building colors each have a different flavor, which is also useful in creating unique strategies.

The game has 20 goals, which provides lots of replayability. Public goals and your private goal will impact the way you play the game because they are worth a lot of points.

Despite a singular strategy, the goals change the way you play. Public goals are an excellent addition to the game. They change the value of each tile and the way you play the game. They act as an additional tool that guides the players. The only problem with the private goals is that the selection of goals at the beginning of the game is not equal. I’m not sure if the reward amounts are based on how hard the goal is, how much following those goals will help or hurt the player, or just picked randomly. Some players will get to select goals that align with the public goals, while others may have to pick a goal that contradicts them.

Suburbia also comes with two solo game scenarios. These variants are functional, but I don’t recommend getting this game just to play solo.

The box is right when it says that it takes 90 minutes to play. It takes longer with more players and can suffer from analysis paralysis — when a player considers all the possible options to determine what move to make. If players do that, the game will take much longer than 90 minutes.

Suburbia is also priced high at $60, but you can find copies at around $35-$50.

Ultimately, Suburbia is a decent game that I’ll play every once in a while. If you like the building selection and placement mechanism or enjoy the economic aspect of building up your income and reputation, Suburbia is a great game for you. For me, the singular general strategy and red lines detract from the game enough to make me not want to play it very often. There are other city building games and long games that I will choose to play over this. Because of those two reasons, I rate Suburbia a 5 out of 10.

[star rating=”2.5″]