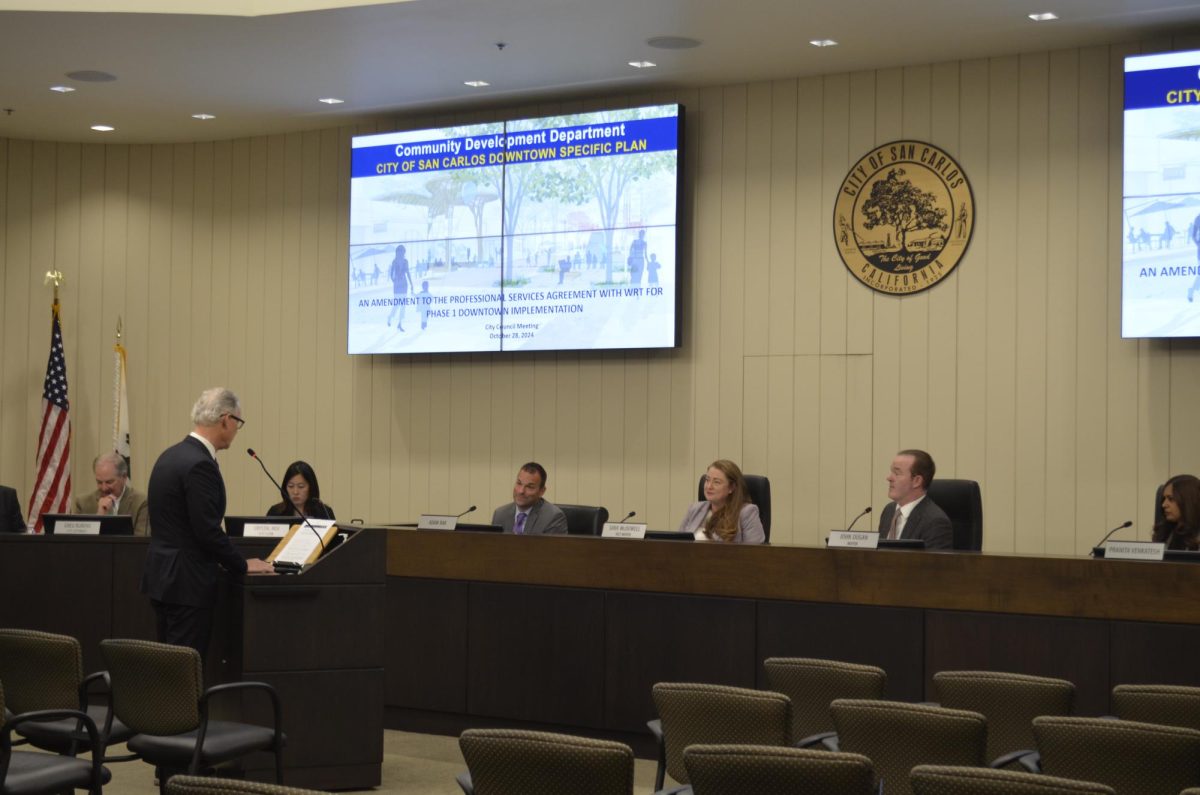

California Assembly Bill (AB) 2839, signed into law on Sept. 17, sets clear guidelines to prevent artificial intelligence (AI) generated deepfakes and other deceptive digital content in elections.

AB 2839 is a legislative bill establishing comprehensive guidelines for using artificial intelligence regarding elections. Lawmakers say this bill emphasizes transparency and information accountability in AI systems to ensure fair elections. Some Californians, however, are concerned this bill violates First Amendment rights.

“AB 2839 is designed to deal with deep fakes in election campaigns. So it contains various prohibitions on creating those kinds of deceptive things for advertising,” said Rex Heinke, partner at Complex Appellate Litigation Group and twice named California Lawyer of the Year by California Lawyer Magazine.

But there are exceptions to this bill: if it’s disseminated knowingly and disclosed as AI, parody, or satire. While AI adapts further, California will provide a civil remedy for elections.

Jax Manning, a junior, says that AI hasn’t yet become advanced enough to fool them.

“I can tell. I don’t know why. I can always tell,” Manning said.

Heinke assumes that AI, like every technology, will get better at some point over time. Cecilia Baranzini, a senior, adds that AI occasionally gets misleading, specifically drawings.

“I think it’s a good idea, but it’s hard to enforce,” Baranzini said.

However, Baranzini thinks it may fall into censorship, but this bill may help with disinformation for safety reasons. According to Heinke, the scope of the bill is limited, with restrictions being placed 120 days before the election and 60 days after. Additionally, the content being created is also finite.

“It only applies to certain people in elections, such as candidates, election officials, and comments about voting machines and ballots,” Heinke said.

Moreover, this bill has a high standard for being deemed a violation of rights.

“A violation has to be proven by clear and convincing evidence. The normal standard in civil cases is just preponderance of the evidence,” Heinke said.

According to Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institution, the preponderance of the evidence is defined as “the evidentiary standard necessary for a victory in a civil case.”

“So to have a violation here, you have to have malice, which is defined as making these things while knowing they’re false or with reckless disregard of their truth. It requires showing clear and convincing evidence to establish that, making it a higher standard. I think it has been carefully drafted to try to avoid First Amendment problems,” Heinke said.

Despite this, a lawsuit was filed on the same day, claiming that the bill restricts “free speech rights, and the rights of others, against an unconstitutional law.”

This AI deepfake “parody” video of Kamala Harris depicts her campaign in a negative light. The creator of this video filed the lawsuit.

The bill’s intent, in a press release according to California Assemblymember Gail Pellerin, is “an urgent need to protect against misleading, digitally-altered content that can interfere with the election.”

Heinke corroborates this and says that this bill is focused on combating misinformation and false information while promoting public trust so that the public can rely on what it sees on the internet, on a TV station, or in a newspaper. Additionally, it gives people a remedy to the situation.

For example, in a Truth Social post, former President Donald Trump posted an alleged AI-generated image of Taylor Swift fans and another depicting her with the words “Taylor wants you to vote for Donald Trump.”

This isn’t the first time AI-generated images of Taylor Swift have been posted online.

“This is exactly the goal of this law: to prohibit that kind of thing, to make it illegal, and to give Taylor Swift a remedy to prevent that kind of false statement about her views,” Heinke said.

Whether or not people can still discern the difference between AI and real life, this legislation provides a civil course of action.

“So if you were Taylor Swift, you can go to court, sue, get an injunction, get damages, and get your attorneys fees,” Heinke said.

Moves are also being made to protect people’s rights against AI. For example, bill AB 2602 gives people control over digital replicas of themselves, according to Professor Mark Lemley, the William H. Neukom Professor of Law at Stanford Law School.

“The goal of the bill is to prevent people from signing away general rights to their images so they can be depicted by AI versions in the future. The bill doesn’t prohibit the use of digital replicas, but it requires that any agreement be specific about what the replica can be used for,” Lemly said.

Lemly says that this bill doesn’t directly regulate misinformation, making it somewhat harder for their image to be used in misleading ways.

Even as AI advances, legislation is also catching up.

“Citizens have to be careful when they see things and try and figure out whether they’re fake or not; sometimes you can tell they’re fake, and I think sometimes you can’t,” Heinke said.