Whether you were closely following the California recall election that ended Sept. 14 or not, you likely saw at least one advertisement for it while using your streaming services.

Throughout California, playlists, YouTube videos, and movies were disrupted by the voices of the most influential people from each party. For the Democrats, Barack Obama, former U.S. President, and Bernie Sanders, activist and U.S. Senator, frequently appeared on the screens.

In other advertisements, Larry Elder, the favored Republican candidate to take over the state of California in Newsom’s stead, spoke fervently about his goals for a state that was “declining” in everything from affordability to education.

However, rather than advocating specific agendas, many of the 20-30 second ads focused on undermining the position of the opposing party, openly attacking their views.

This left many Californian voters feeling pressured to believe one side or the other, creating a situation where they had little opportunity to weigh the actual policies that would change as a result of the recall.

The concept of political advertising goes back to the early 1900s, when entertainment and media began to emerge from the sidelines of American politics. As television became a standard in homes across the country, most speeches, debates, and campaigning ads were featured on screen, growing in complexity as technology progressed.

According to TIME writer Kathryn Cramer Brownell, the primary purpose of the first political advertisements was to “help [candidates] not simply convert voters, but more importantly, activate nonvoters.” However, throughout the last several decades, there has been a significant shift in the way marketers have approached this task.

At first glance, this shift in marketing strategy can be associated with advances in technology. Although this is profoundly influential on advertising methods, the main stimulus for such an abrupt change is the divide between the two major American political parties- Democrats and Republicans- and the integration of propaganda-esque elements.

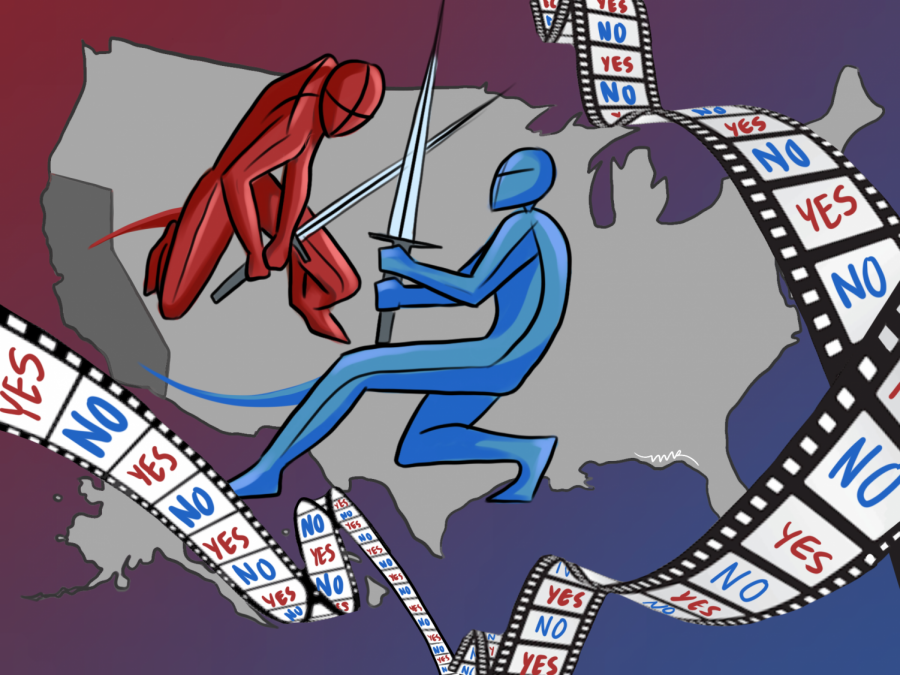

Over the course of several months prior to the California recall election, millions of dollars were spent by Democrats and Republicans alike to promote their positions. Voting “Yes” to the recall or voting “No” became the difference between siding with or against anti-vaxxers, with or against the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions.

The association of each party with major controversial issues that often don’t reflect the views of the entire party has led to marketing with predominantly emotional appeal rather than material appeal. This presence of emotional manipulation that is often unsupported by facts is one of the central characteristics of propaganda. With that said, what can be done to minimize the negative impact of political propaganda and secure thoughtful choices at the voting polls?

For the voter, the next steps are to filter information and fact check what they see online, and most importantly to be aware of the political manipulation that can result from the current party-dominated political system.

For the marketer and politician, future action must be centered on allowing Americans the right to “free thinking” by creating ads that allow for personal interpretation. Limiting propaganda and making the goal of political advertising to inform rather than to manipulate should become a top priority.

Finally, as a country, we need to take a step back from the two-party political system and rethink what characterizes us, realizing that political allegiance should not be above compassion and unity. Pushing out anti-opponent propaganda silences the voter’s ability to view the agendas of each candidate through an unbiased lens, and could lead to the restriction of political freedom.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop editorial board and was written by Maya Kornyeyeva.