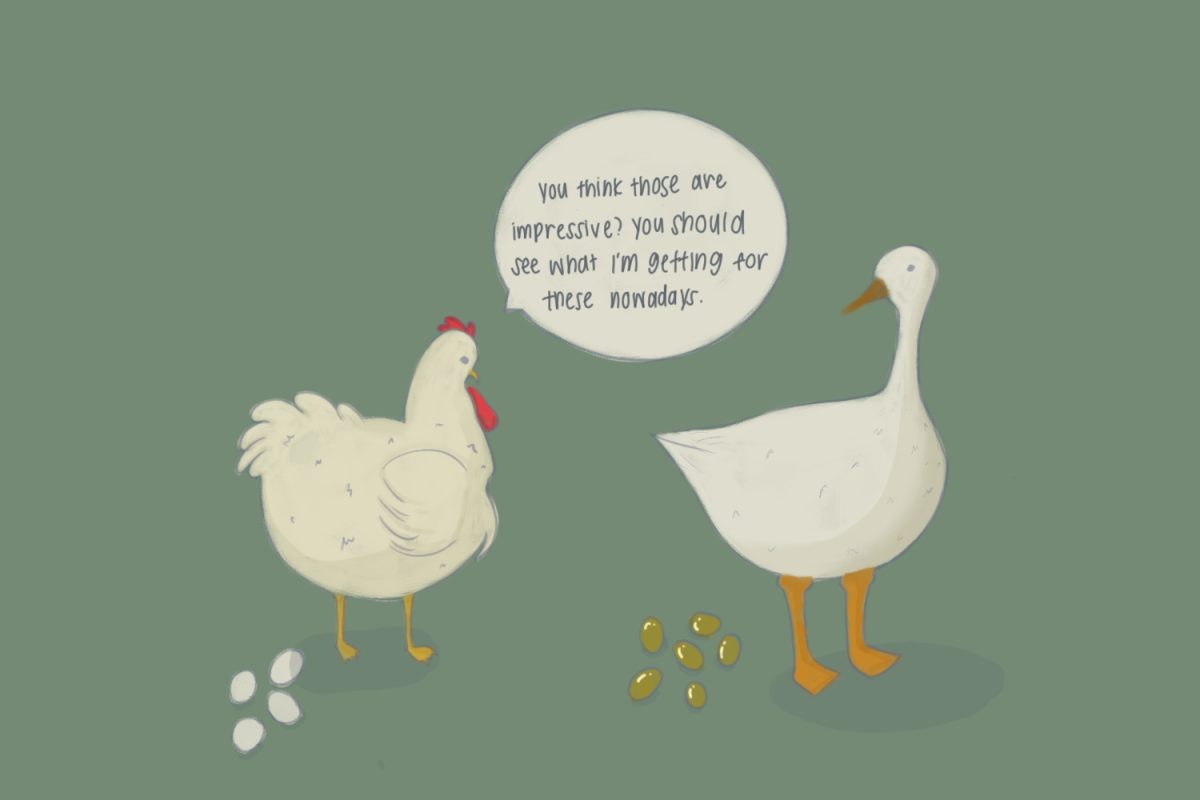

Villains can be some of the most memorable characters in the media that we consume. Done right, they can evoke a blend of fear, anger, and awe from an audience member. But too often, writers and producers rely on tropes that revolve around conditioned responses of disgust, rather than writing a full, compelling character.

One area where this could not be more apparent is in queer coded villains, especially men. Queer coding is when a story suggests, though does not usually outright say, a character to be queer. Many stories in popular media include subtext that implies a male antagonist to be gay or bisexual. Instead of creating fear of the character for what they’ve done, these tropes play on homophobia to create revulsion instead.

Take, for example, James Moriarty from the popular BBC show “Sherlock.” While his sexuality is never explicitly mentioned as gay, there are multiple, very overt references to his homoerotic inclinations.

Earlier in season 1, episode 3, Moriarty introduces himself as Jim from IT and intentionally acts as though he is romantically interested in Sherlock Holmes. Later in the series, he even explicitly makes references to the “stamina” of his male bodyguards.

In examples such as these, the viewer is revolted by the weird, obsessive acts of the villain, compounded by the fact the villain is doing it to another man. Though it isn’t in all media, this trope is far more common than one might think.

This trope is also not new. The play “Faust“ by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe features Satan (in the play called “Mephistopheles”) as homosexual. During the last act of the second part, rather than claiming Faust’s soul, he instead pursues the archangels who have come to purify Faust. Though he was under the influence of aphrodisiac rose petals dropped by the angels to make his demon companion flee, the queer behavior added to the disgust for Mephistopheles felt by an audience member.

Even more famous examples can be found in dozens of Disney movies, where male villains are often dramatic and effeminate, far more so than their male protagonist counterparts. Hades from “Hercules” and Scar from “The Lion King” are two notable examples.

Even when villains have a decently written character, choosing to drop in queer coding to exacerbate fear felt by audience members is a lazy and prejudiced move. It plays off the subconscious prejudice that gay means bad and that effeminacy in men is degenerate and evil.

Diversity isn’t what queer people should want– that’s been around for centuries. It’s quality representation, free from a desire to exploit subconscious homophobia, that we should be looking for.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop editorial board and was written by Anita Beroza.