High school students are chronically stressed, and it doesn’t take a genius to see why.

Students sprint through jam-packed schedules stocked to the brim with homework, sports practices, test prep, volunteering, and other demanding endeavors. A dizzying array of commitments means some leave the house at 8 a.m. and don’t return until over 12 hours later.

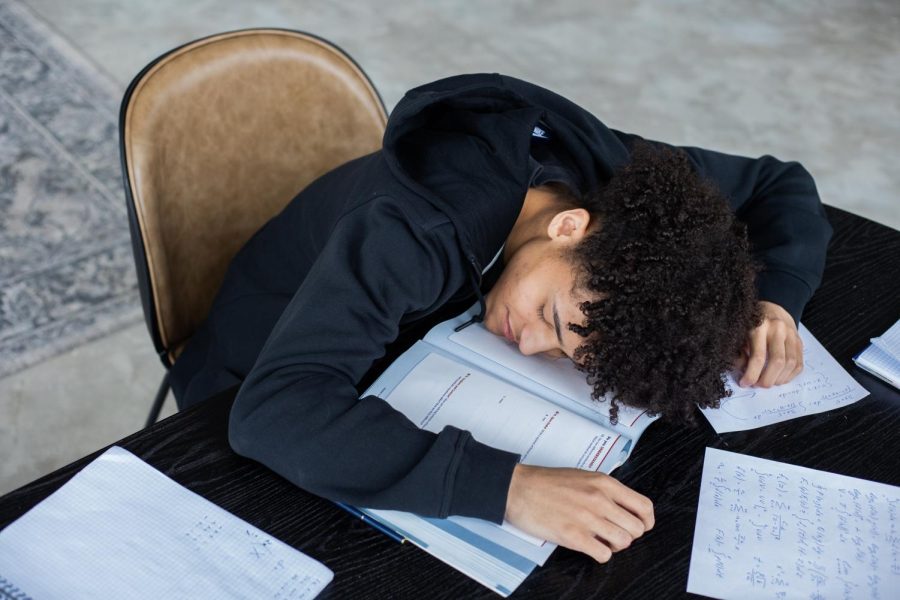

Don’t be fooled; they’re not returning home for a good night’s rest. Growing academic demands dictate their sleep schedule, if they even sleep at all. I don’t even bat an eyelash when peers complain bleary-eyed they didn’t make it to bed until 3 a.m, most likely because I was doing the same thing.

It’s become cultural currency to equate the rigor of the classes you’re taking with the amount of stress experienced by students and the sleep you’re getting, or lack thereof.

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, adolescents aged 13 to 18 are recommended 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night. According to a report done by the CDC, 72.7% of high school students get fewer than eight hours of sleep each night.

Nationally, nothing has been done to address this, and the problem is worsening; the percentage of high school students reporting adequate sleep has dropped from 30.9% in 2009 to 27.3% in 2015.

But action needs to be taken. The effects of sleep deprivation are no secret; according to the Institute of Medicine, chronic sleep loss can be associated with hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart attack, stroke, anxiety, and depression.

Despite this, pressure to pack courseloads and extracurriculars with rigor only continues to grow. Students are encouraged to do just about anything to give them a leg up in college admissions, irrespective of mental health, adequate sleep, and healthy stress levels. The pursuit of a 4.8 GPA and an impressive resume has caused sleep and wellness to take a backseat.

There is a collective need amongst high school students to be overachievers, especially in the Silicon Valley. Still, it comes at a cost, and mental and physical health should never be compromised for a letter grade that will be irrelevant in a decade.

It’s not sustainable for students to spend eight hours at school, another two to three for after-school sports practices, and another two to four for test prep sessions, volunteer shifts, or other extracurricular activities. This is how you foster burnout and how once ambitious students with an omnivorous appetite for learning become discouraged by a system that prioritizes productivity over the well-being of its students.

So how do we fix this?

Students need free time. We live in such a blur that time reserved for introspection is next to none, and unstructured chunks of time in high school laughably do not exist.

Teachers implementing work periods could help reach this objective.

During the 2020-2021 school year, students were given Wednesdays off as asynchronous work time. This asynchronous day was met with positive feedback from many students, who felt it made it easier to balance their workloads. We should integrate these work periods during the week again, where teachers set aside one class period per week dedicated to allowing students a free period. Each department can collectively agree that X day of the week would be used for students to have a free work period.

Some might say that unstructured time and lack of teacher instruction will result in no work getting done, but arguably the Bay Area fosters some of the most ambitious, determined students. They will be inclined to use work periods because it will benefit them by alleviating stress and freeing up time for preexisting after-school commitments.

But when addressing this concern, we also must ask ourselves if it would be so offensive if students used free periods to relax or sleep.

For a demographic who reports stress levels higher than people 30 years their counterpart, would it be the worst crime to allot them an hour to work how they please?

When did the point of schooling become to raise achievement, to so narrowly only focus on scores, accolades, awards, and leadership?

The first sentence of Carlmont’s mission statement reads: “The mission of Carlmont High School is to provide a supportive learning environment that allows all students to achieve success in academics and careers.”

If it is only success they are after, and not enrichment and well-being, the school does seem to accomplish this. Many of its students attend good colleges and have impressive credentials. But many of their students are also sleep-deprived and stressed.

The tornado of achievement that whirls through Carlmont is impressive and commendable, but it’s also dangerous. Students are humans, not mindless robots who bushwhack through mind-numbing assignments, invincible to sleep deprivation, sickness, and mental health functioning.

Instead of academics being used as a ticket to success in all future endeavors, it needs to be characterized as what it should be: a way to learn and grow. We need to provide an environment that encourages this and helps ease students’ heavy burden. Work periods are a simple and effective way to do this.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop editorial board and was written by Marrisa Chow.