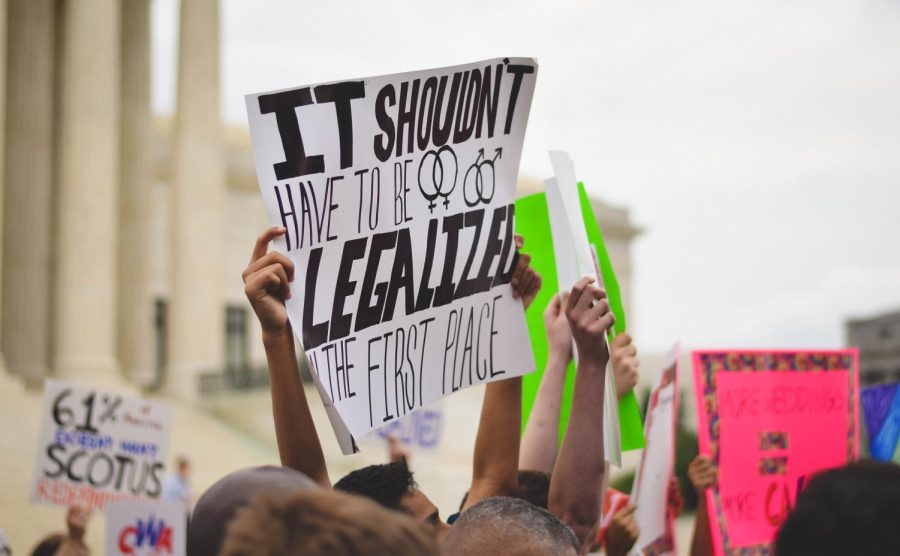

In the wake of recent arguments in the Texas and Mississippi abortion cases, critics of the U.S. Supreme Court have publicly questioned its legitimacy as its members consider overturning long-standing judicial precedent.

These critics are not solely limited to the press, pundits, or politicians. Even members of the court itself are criticizing the actions of their colleagues and asserting that their decisions will undermine the judiciary in the long-term.

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the Constitution and its readings are just political acts?” said Justice Sonia Sotomayor during the debate over Mississippi’s ban on abortion after 15 weeks.

Even Chief Justice John Roberts, who was appointed by former President George W. Bush and generally recognized as a solidly conservative jurist, has expressed deep concern about the future of the court. In a strongly-worded opinion published along with the Texas ruling, Roberts joined the three remaining liberal justices — Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Steven Breyer — to argue that the “clear purpose and actual effect of [the Texas law] has been to nullify the court’s ruling.”

Citing precedent such as Marbury vs. Madison, the 1803 landmark decision that established the principle of judicial review, Roberts noted that allowing these laws to continue existing would threaten the fundamental structure of the Supreme Court and further undermine the principle of judicial review.

Since the Texas law has primarily been seen as an attempt to subvert the long-standing precedent of Roe v. Wade, Roberts called upon his fellow conservatives to push back against conservative lawmakers who seek to undermine precedent.

Roberts said, “The nature of the federal right infringed does not matter; it is the role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system that is at stake.”

The two justices’ concerns about the future of the court, though, take on even more urgency when put in the context of the political process that resulted in the current majority of strongly conservative judges who will be making the controversial decisions.

In early 2016, after the death of former Justice Antonin Scalia, former Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and fellow Republicans announced that they would not even consider a nomination to fill the seat until the next president took office nearly 10 months later. This political power play blocked former President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland (a well-respected member of the federal court of appeals) and laid the foundation for the conservative majority we see today.

McConnell tried to justify his choice to stonewall consideration of the nominee by citing precedent in his 2016 announcement.

McConnell said, “All we are doing is following the long-standing tradition of not fulfilling a nomination in the middle of a presidential year.”

Yet, this simply isn’t true. According to the New York University Law Review, presidents generally have success nominating and appointing court replacements and specifically in the handful of cases in which the process played out during an election year.

Upon reflection and after anticipating a nomination opportunity in the final year of the Trump administration, McConnell attempted to revise his justification in 2019.

McConnell said, “[Y]ou have to go back to … 1880s to find the last time … a Senate of a different party from the president filled a Supreme Court vacancy created in the middle of a presidential election. That was entirely the precedent.”

However, McConnell’s second claim was also false. Since 1880, there have been two more recent cases of confirmations when the Senate is controlled by the opposite party. In 1988, Justice Anthony Kennedy was confirmed by the Democratic-majority Senate in a unanimous vote of 97-0, according to the Brookings Institution. Similarly, President Dwight Eisenhower made an uncontested October 1956 appointment of Justice William J. Brennan.

In short, the political process – and specifically Senate leadership – has historically honored the constitutional obligation to consider a Supreme Court nominee in a reasonable and timely manner.

The Garland incident itself would put the court’s legitimacy in question if the replacement justice made the difference in critical decisions. But in 2020, McConnell, faced with a Supreme Court vacancy due to Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death less than two months prior to the upcoming presidential election, fast-tracked former President Donald Trump’s nomination of Justice Amy Coney Barrett in less than 30 days to pack the court with a sixth conservative vote.

The asymmetrical treatment of the two nominees in 2016 and 2020, which was based purely on political power, taints the nomination process and ultimately the legitimacy of the Supreme Court as an institution. The court that resulted from that process now threatens to eliminate fundamental rights that have been recognized for decades.

The solution is simple: the Senate should establish a requirement that forces a nominee to be considered within a certain period of time after the nomination, regardless of who controls the Senate. Senators can always choose to vote against a nominee, but the process should play out, and the nominee should get an appropriate hearing from the Senate.

McConnell’s actions have produced one of the most ideologically divided and conservative courts that our country has experienced in the last 100 years and one that has signaled it will upend key parts of U.S. jurisprudence.

Earlier this year, Barrett told an audience that she wanted to convince them that the court “is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks.” Unfortunately for her and the rest of the court, the disparate treatment of these two nominations has left behind a stench of politics that will be hard to get rid of.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop editorial board and was written by Hudson Fox.