Greetings, adventurer!

Welcome back to The Lord of the Reads, a blog about science fiction and fantasy (SFF) books. Today, we’ll be discussing young adult SFF, and how it’s perceived by the larger community of readers. So, pull up a chair, kick off your travel-worn boots, and get ready for a spirited debate.

Young adult literature.

In my experience, it is one of the most ridiculed subgenres to exist in science fiction and fantasy. Fans groan when you mention Divergent or The Mortal Instruments, complaining about “cringey” plotlines, love triangles, and the ever-controversial “Mary Sue.” Despite YA’s negative connotations, however, I’ve found that there is real value in these books.

By labeling a book as YA, you’ve already damaged its perception by readers. Why is that?

Many SFF fans view YA as shallow, formulaic, and trope-y, and they’re not always wrong. I’m not the ride-or-die YA fan I was in middle school anymore, so I can see that there are some legitimate reasons why people tend to complain about it. Love triangles and the “Chosen One” storyline are both classic YA tropes, and they do get old pretty fast. After the ninth or 10th variation of “you’re a wizard, Harry,” you start to get the point.

There are also some very valid criticisms about what many of these books might be telling readers: the late 2000s and early 2010s saw a trend of YA protagonists being “not like other girls,” perpetuating the idea that women and girls should be competing with instead of celebrating each other. This has gotten better over recent years, but it remains an issue that should be discussed.

Still, it’s interesting to see that a field full of female writers, catering to a largely female audience, receives such contempt from the wider genre. It reminds me of something I read about The Beatles: when they first gained popularity, mostly among teenage girls, they were derided by critics as a “god awful” passing fad. Now, decades down the road, they’re hailed as one of the best bands of all time. It makes you think: considering the creators and their target audience, is the hate that YA gets all deserved, or is it a symptom of a wider problem of dismissing female writers and readers?

So, is YA actually valuable?

Short answer: yes.

Longer answer: it’s complicated.

YA is no different from any other field of SFF: some people love it, some people hate it, and some people just don’t care. Ultimately, I think that YA holds greater value than we give it credit for.

Probably the most obvious reason why it’s so important to the wider genre is that YA serves as an entry point for younger readers. So many readers gain interest in fantasy or science fiction through books they read at an early age, then branch out as they get older. Without series like “Harry Potter,” “Percy Jackson,” or “The Hunger Games” to introduce kids and teens to the wider world of SFF literature, readership would simply not be what it is today. Science fiction and fantasy owe more to YA than many fans care to admit.

YA has a large percentage of young readers, but it remains significant for a large amount of older fans as well. Many people, myself included, grew up on authors like Cassandra Clare, Sarah J. Maas, and J.K. Rowling (side note: she sucks). I read my first book by Clare in seventh grade and immediately fell in love with the “Shadowhunter” world. I read everything by Clare that I could in the span of two years, and her books were a significant part of my middle school experience. I still love them, and though they don’t hold the same magic for me that they once did, the fact remains that they meant a lot to me during a formative time in my life. For this reason, I think I’ll always enjoy rereading them for nostalgia.

However, my experience isn’t unique. I took a survey of other Carlmont journalism students, and a lot of their favorite SFF books were geared towards young adults. For senior Zachary Khouri, the “Throne of Glass” series by Sarah J. Maas has had the same effect as the “Shadowhunter” books had on me.

“Those books defined [my] adolescence for better or for worse,” Khouri said. “I began reading them when I was in sixth grade and finished it in sophomore year. They were messy but engaging.”

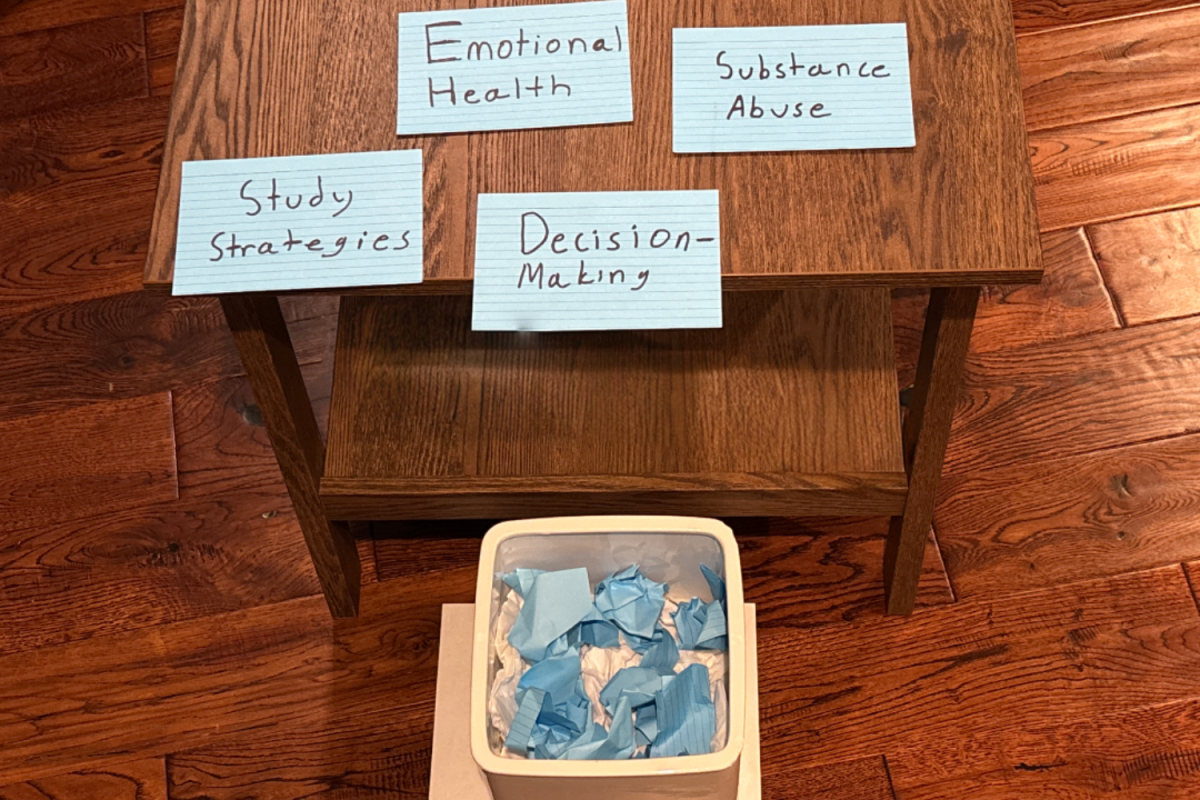

YA is also significant beyond simply being an entry point into the genre or a source of nostalgia for older readers. One thing I’ve come to realize lately is how indicative it is of the teenage experience. Of course, typical adolescents aren’t confronting demons or killing dark lords on a daily basis, but they are experiencing a lot of the same problems that YA protagonists face.

To continue with the Clare examples, let’s look at Clary Fray from “The Mortal Instruments.” Throughout the series, she has to grapple with a new identity, come to terms with a family history she would rather bury, deal with tangled interpersonal relationships, and, of course, prevent her insane father from taking over the world.

Sound familiar? As teenagers, our lives can be as chaotic as the books we read. We deal with personal issues like relationships, school, and family at the same time we are trying to determine our place in the world. We are gaining a greater awareness of the world around us, and the problems that plague it, while also trying to make it to class on time every morning.

A hallmark of YA is the way it blends the small, seemingly insignificant ups and downs of adolescence with ridiculously high stakes. We may not be dueling our parents for the fate of the planet (at least not usually), but we are fighting crucial battles of our own. Students press for climate action, racial justice, and social equity. We vote, march, speak, and strive for our futures in the same way that the protagonists we read battle monsters and magic. That’s what makes YA so important: it captures the teenage experience in all its complicated, magnificent, messy glory. That’s how so many readers connect with it, and why, despite its flaws, it remains so popular.

In conclusion

I never actually expected to write this article. I tend to stay away from YA these days – it’s just not my favorite anymore. Though I used to buy into the idea that it wasn’t “real” SFF, I’ve come to realize over the course of writing this series that the conceptions we assign to certain types of books aren’t always accurate.

Young adult SFF is indeed written for a younger audience, but why should that diminish its value? These books have things to say: within them, I’ve found incredibly meaningful explorations of mature topics from immigration, race, and sexuality, to gender, human trafficking, and power structures. Whether it’s seen as a gateway into the wider genre, a source of nostalgia, or a powerful subgenre in its own right, YA remains just as valuable as any other part of SFF. Regardless of personal opinion, it’s time for young adult fantasy and science fiction to be considered a legitimate part of the genre.