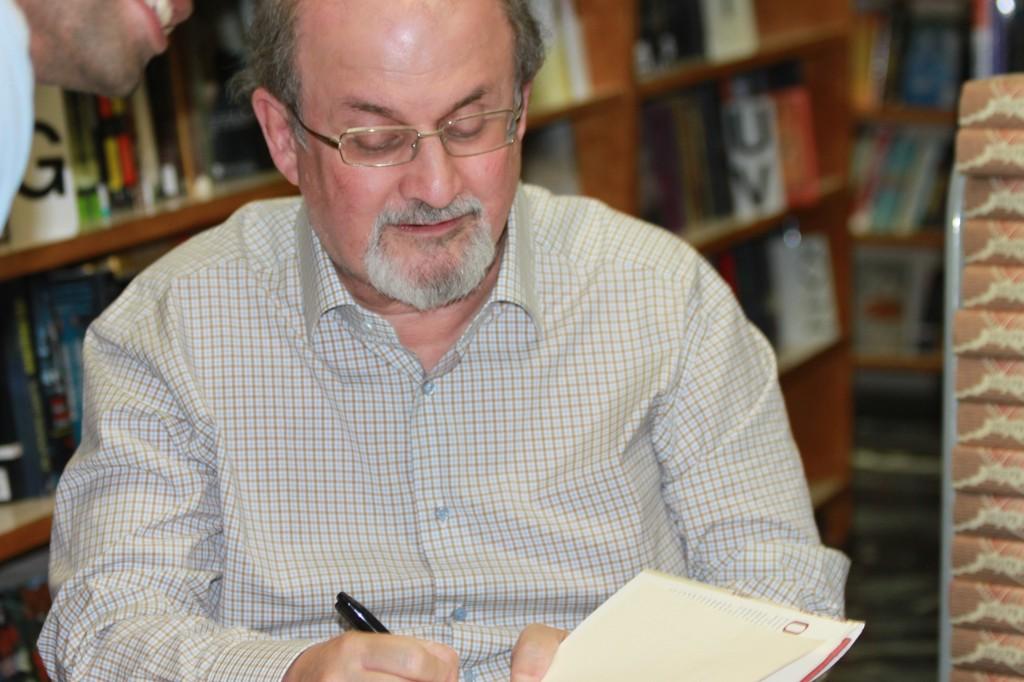

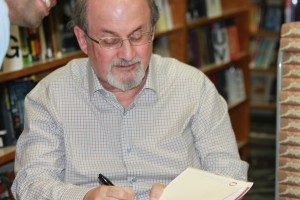

[media-credit name=”Asha Karim” align=”alignnone” width=”300″] [/media-credit]On Sept. 25, an international icon visited Kepler’s Bookstore in Menlo Park to speak about the controversy surrounding his work and the experience of years spent in hiding amid threats against his life; and all unknown to the vast majority of our student body

[/media-credit]On Sept. 25, an international icon visited Kepler’s Bookstore in Menlo Park to speak about the controversy surrounding his work and the experience of years spent in hiding amid threats against his life; and all unknown to the vast majority of our student body

Sir Salman Rushdie is an Anglo-Indian writer, whose novels earned him both high acclaim and high risk. Midnight’s Children, his first novel, portrayed an allegorical view on modern India. His second, Shame, detailed a story of politics and sexuality intermingled.

While both titles were prominent, none held more ramifications for Rushdie than his third in 1988, The Satanic Verses, which provoked Muslim protests, and led Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa calling for his death.

Rushdie would remain in hiding until 1998 under the protection of the British government, at the cost of British taxpayers. His years of hiding meant sacrifice on both his part, and on that of his loved ones, and is the subject of his latest book.

Rushdie had to move upon discovery of his identity by even so much as a doorman. Should a contractor have to repair the roof, he would have to hide in the bathroom, his escorts drove evasively to avoid being tailed; Rushdie said he “bore the habitual sweat of shame.”

Friends and family breathed not a word about his location, however, though their relationships became very strenuous due to the protective proceedings and fear of discovery that was ever-present.

“You get through it because people help you get through it,” commented Rushdie, whose decade off the grid took a huge toll on him. Those who saw him during and after his ‘rough’ decade claim he looks younger now, which Rushdie attributes to the acute stress of the situation. “I had an overwhelming urge to be one of those people at a cafe, just having a cup of coffee, instead of in my motorcade,” Rushdie confessed. “Tt seemed improbable I could have that for a long time.”

Some speculated that the controversy surrounding Rushdie’s word was intentionally stirred up, and his books kept on shelves simply out of arrogance and greed. Some British taxpayers were upset at the extent of the cost of Rushdie’s defense, though it was backed by several governments, including our own.

Despite criticism, however, “a great deal more is spent to protect Prince Charles and he’s certainly written nothing of interest,” said Sir Ian McEwan.

Rushdie’s concern regarding freedom of speech and expression is affirmed as his, and many other texts, are banned in foreign countries or pulled from curricula and syllabuses of their universities. While he finds the decline of these rights alarming, he doesn’t blame it on the western world. “There is a point beyond which you can’t blame the West for everything, it is a self-inflicted wound,” Rushdie added.

In this sense too, he did not find that staunch opposition or extremism speaks for the whole of such countries. He claims there are many countries who dislike the way extremists portray them, and as in the case of the embassy altercations in Libya recently, while he does not believe much can be done from the outside, he finds it was encouraging to see pro-American demonstrations occurring to show that such terrorism certainly does not resonate for all Muslims.

While Rushdie’s years have been a harsh, they have yielded potent works of written art and a wealth of experience and insight as to progress and setbacks in affairs both internal and international. “History takes a long time,” Rushdie commented. “It doesn’t operate according to the news cycle, and it does not go in a straight line.”