To be censored is to be silenced.

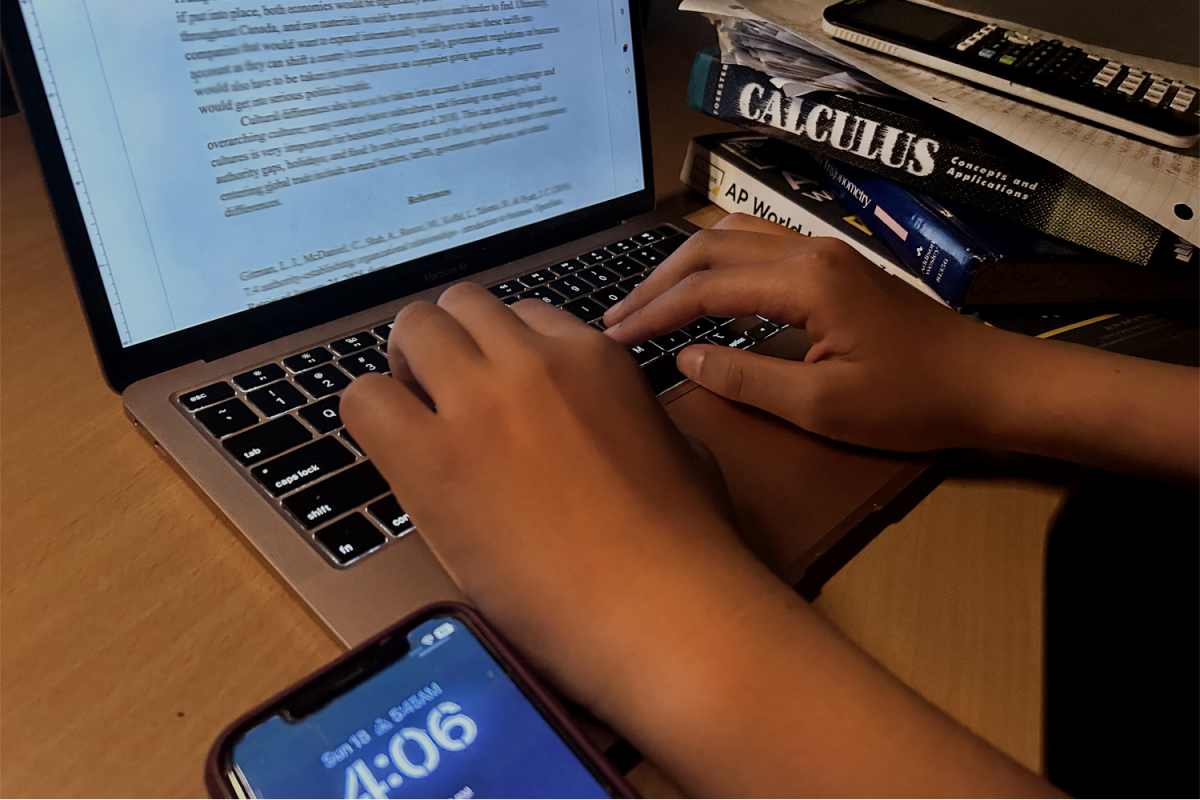

Censorship of high school student media is a widespread and serious problem today in the world of journalism. In many states across this nation, principals, superintendents, and other education officials step in to ensure that anything their students publish meets specific criteria that these overseers set.

They will, without approval, edit, censor parts of, or even completely remove the hard journalistic work of many a student without consent. This censorship can be done for any number of reasons, ranging from not matching the administrators’ viewpoints to even having the slightest chance to cause controversy. And all of this is perfectly legal.

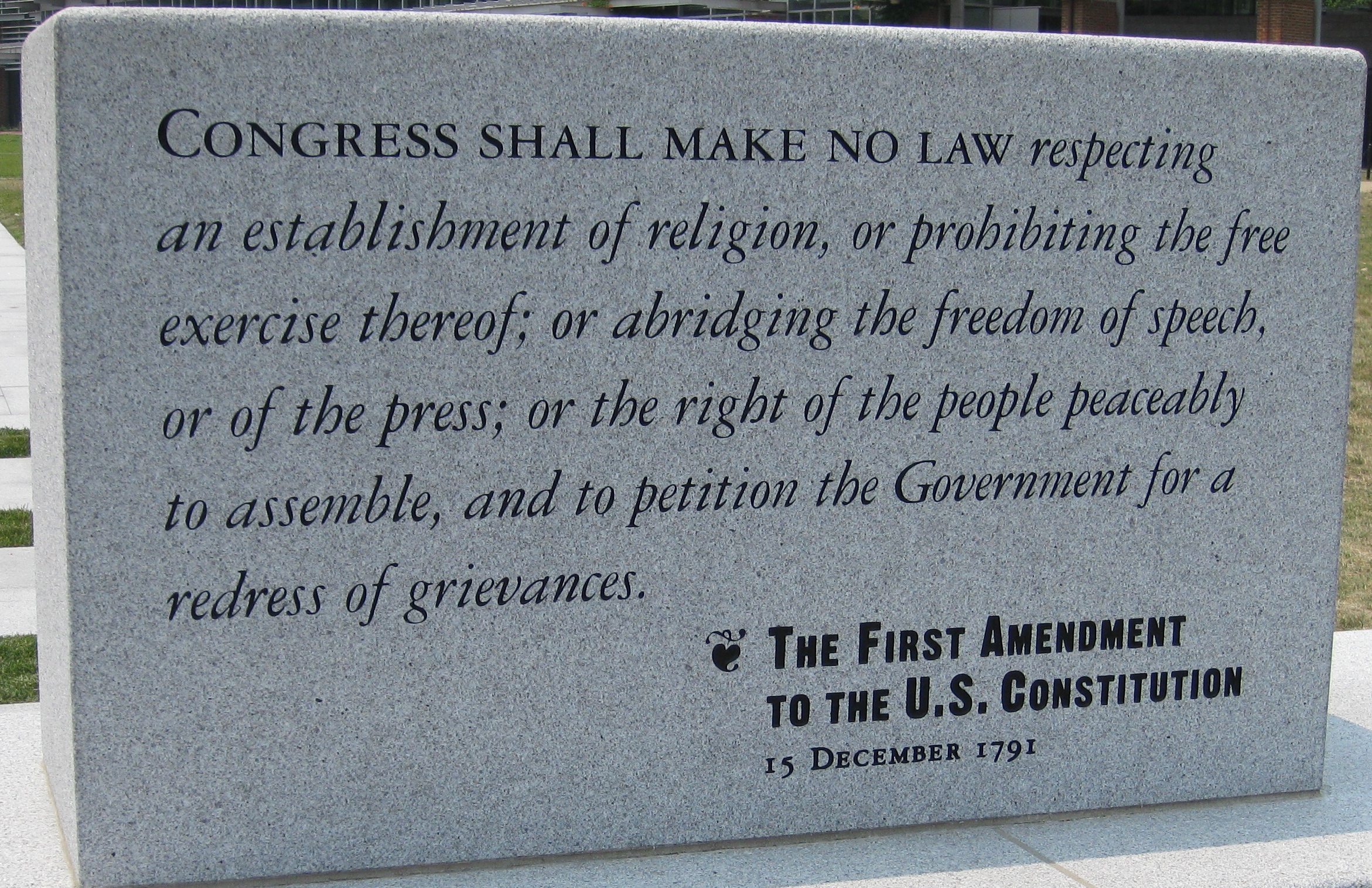

In 1988, there was a case in the Supreme Court named Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier. The Supreme Court ruled that administrators at Hazelwood East High School, located in St. Louis, Mo., could legally censor student- run articles that had concerned teen pregnancy.

This led to a vast reduction in First Amendment rights among student journalists, and changed the way student media can be defined as an “open forum” for student expression. Without the designation as an open forum, administrators gained the right to censor whatever they saw fit among themselves.

All of this was explained to me, a newcomer into the world of student journalism, at the JEA/NSPA Spring National High School Journalism Convention in San Francisco. I was blown away by this newfound knowledge. Not only had I not known of the injustices that were occurring so frequently across the country, but I also knew that most of my fellow Carlmont students had almost no idea either.

While I listened to journalism advisers that hailed from far away places such as Ohio and West Virginia, I was appalled to discover that many of them were part of movements that attempt to gain more rights for student free expression, and fail year after year.

One young female journalist piped up from the back during a question and answer session, “I know you guys are trying really hard, but I’m wondering why not much is really getting done.”

The speakers were silent for a few seconds, before one of them gravely nodded and said, “Well, she’s right.” The speaker went on to say that really the only thing that they could do would be to press on and have hope.

I found this to be very disturbing. How could there be such little backing behind these movements that they continuously run into the wall?

I believe what legislators need to hear is more student involvement. While many student journalists are already heavily involved in the endeavor for greater First Amendment protection, there must be many more if there is to be no censorship in every state.

The right of students to openly express their opinions in the media is a right that should be cherished, not limited. The only way for students to be able to speak and write freely is for them to speak out.