“Most immigrants believe strongly in the American Dream. That is what brings them here. I wish some young Americans had that dream, as much as immigrants do,” said Margaret Sands Orchowski, an author of “The Law that Changed the Face of America” and a congressional correspondent of the U.S. Congress.

Whether it’s success measured in happiness, material possessions, or wealth, success comes to those who work hard. In a world of endless possibilities, everyone has an opportunity to achieve their dreams, but only if they are willing to take the chance to do so.

From floating on rough, choppy waters to a challenging first few years in America, MJ Pham remained motivated despite facing what seemed to be impossible problems. Everyone has a different idea of the American Dream, but he saw America as an opportunity, a place with hope.

“The American Dream is not seen as the universal milestone of achieving financial success in America, which is the commonly understood definition, but it is analyzed as a dominant narrative or a powerful story that is publicly told to dictate what success is,” said Professor Seon Hye Moon, an Ethnic Studies teacher at the College of San Mateo.

Escaping Vietnam: A Journey Through Adversity

Bac Liêu, a city in Vietnam, was left by Pham and many others who escaped the echoes of the devastation the Vietnam War brought. There was never a guaranteed “tomorrow” during the Vietnam War. Pham recalls that he would live in constant fear every day.

“The North often bombed the South; they bombed a lot of schools, daycares, and orphanages,” Pham said.

Pham grew up in an orphanage with six non-biological siblings. In an effort to get adults to surrender, children were primary targets during the Vietnam War.

One night in 1994, when the moon peaked, and the sun was far from rising, Pham, then 28 years old, and his six siblings snuck onto a fishing boat.

More than 100 souls were huddled around the small fisherman’s boat in an attempt to leave the country. Like a cake, men lay on the bottom, women, children, and finally, fish were laid on top to hide them, but this was no sweet journey.

“When we got to the boat, there were already a lot of people there,” Pham said.

Being snuck onto a boat wasn’t free. To be taken on board, many people lined up with their payment — two bars of gold.

As the fishing boat traversed rough waters, more than a hundred bodies gathered together, wishing for, but not guaranteed, a new life. Their breath synchronized with the waves.

“They gave us a straw to put in our nose, which allowed us to breathe,” Pham said.

Almost all of the passengers on Pham’s boat died, while others sank, got lost, and were even taken down by government surveillance. He and many others were floating on the open sea for around two months before they were rescued by ships from Norway.

Many people in Vietnam also tried to escape around the time Pham left. From 1990 to 1999, 38,687 people left Vietnam and immigrated to the U.S., according to The U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

“The Norwegian boat took us to Indonesia, where I stayed for six months,” Pham said.

In Indonesia, Pham had to undergo many blood tests like Hepatitis B and DNA tests.

“When I took a (DNA) test, they found out that I was half American, just like my biological father, an aberration. So I got to go to America,” Pham said.

When Pham was younger, he noticed that he looked different than other kids, and now he knew why. From that point in time, his American blood gave him passage to the U.S. and an escape from a country that didn’t want him.

“My mom’s country was so bad, without hope, without dream,” Pham said.

Stepping Foot in America:

Surrounded by all the loud noises and bright lights, Pham knew he wasn’t in Vietnam anymore—cars whizzed by, a stark change in scenery of the mopeds that once dominated his hometown.

“Everything wow, everything big,” Pham said regarding his first impression upon stepping foot in the U.S.

Welcomed by a Catholic church in West Virginia, Pham found a place to stay and his first job.

“The church took us in and helped us find jobs. They had us clean people’s homes,” Pham said.

Pham struggled with illiteracy when he arrived in the U.S. He was unable to communicate with others, restricted to only hand gestures and a smile or a frown. That is what Pham was limited to; because of this, he navigated his way to an education.

“I had to go back to Vietnamese school to learn how to read,” Pham said.

But as he grew more familiar with America, he worked hard to get a better education, to better himself. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice, went to law school, and even got his Juris Degree.

“But personal issues changed, and I became a single dad,” Pham said.

After his final child was born, Pham’s wife passed away due to cancer. He moved to California to be with his wife’s family to receive help in caring for his kids.

Around the time Pham immigrated to California in 1990, 21.7% of California’s population was made up of immigrants, according to the Migration Policy Institute. The Migration Policy Institute reports Vietnamese is the fourth most spoken foreign language at home as of 2021. Around 2.2% of 67.8 million people speak Vietnamese at home over the age of five

However, amidst the linguistic tug-of-war between Vietnamese and English, a more significant challenge appeared — speaking for his son. At nine, his son was only communicating a couple of words.

Pham found out that his son was on the autism spectrum.

He knew he had to take parenting in a different direction, above all the changes he had already made.

A New Vision: Navigating New Beginnings

“I’ve seen it from all sides,” Pham said.

Pham worked with teachers and administrators to help his son receive an education that supported his needs. As a parent, Pham wanted to provide the best future for his son and all his children, just like how he longed for a better future.

He learned how to work with all sides of education since he understood the teachers’ and parents’ points of view; they only wanted what was best for the children.

With his son’s disability, he realized he wanted to give back to all the teachers and administration to help his son’s education. Understanding the importance of education, Pham obtained two additional master’s degrees: one for special education and one for administration.

Not only did Pham juggle multiple familial roles, but he also juggled multiple jobs to support his family. Some people would not expect to find their teacher working in a grocery store, but Pham was okay with doubling up on jobs to support his family.

“You have to be willing to give up anything,” Pham said.

Most of his week was filled with burying his head in work and juggling three jobs. He worked as a teacher from Monday to Friday while working an additional 10 hours on the weekends.

The American Dream is a single phrase with an infinite amount of definitions. To Pham, he has achieved even more than he dreamed of when he first came to America. It was not an easy road, and success certainly did not come instantly, but Pham’s determination paved the way for his dreams to become a reality.

“Dreams are achievable, but you must work very hard,” Pham said.

Reflecting on his journey, Pham believes many people do not realize how fortunate they are to have grown up in the U.S.

While acknowledging the common complaints in America — high gas prices, a homeless crisis, and financial struggles — Pham brings up a different perspective.

“I wish they could go to another country and live there for one month,” Pham said.

Since Pham escaped from Vietnam, his vision of the U.S. has remained unchanged, favoring the country.

“This is the country you want to be in,” Pham said.

Dreaming in America: The Immigrant Perspective

Pham’s journey mirrors many immigrants striving to secure their version of the American Dream.

Every immigrant’s journey is different.

“Diversity of representation is so critical–we need so many more voices, images, sounds, stories to represent the vast spectrum of human life,” Moon said.

ArchBridge Institutes’ survey states that in 2023, 33% of people have achieved their own ideas of the American Dream, 42% are on their way to attaining it, and 24% believe the American Dream is out of reach.

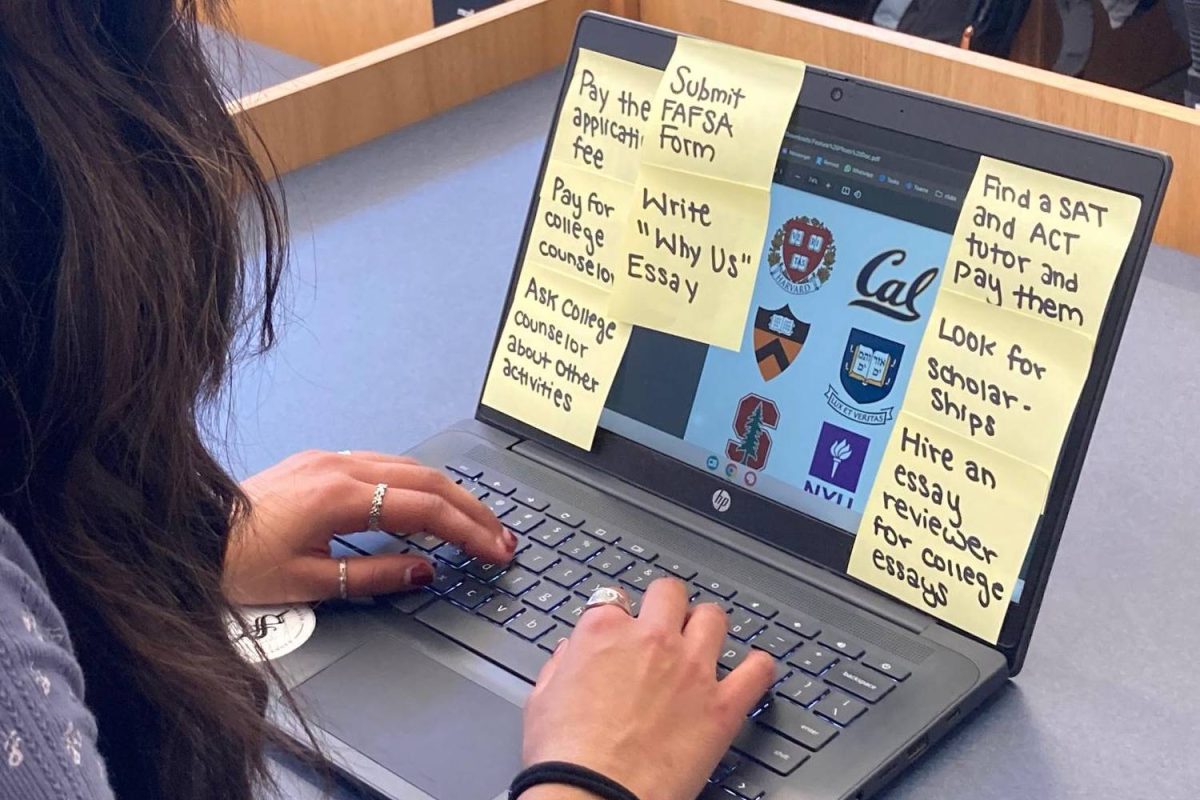

“My parents enforced a very strict academic rigor throughout my childhood,” said Ashlynn Son, a sophomore at Carlmont. “It is very different compared to American families.”

Immigrant parents understand the importance of working hard, as shown through Pham. He knew he had to work hard to build himself up, which further dominoes upon their children to endure challenges.

“Living in the U.S. has its privileges,” Son said.

According to Pew Research, the U.S. foreign-born population will reach 78 million by 2065.

Seoha Kim, a Carlmont student and an immigrant from Korea, recalls his impressions of the U.S. as challenging to adapt to. Like Pham, Seoha struggled with communication in the U.S. when he first arrived in 2019.

“I remember there were many cultural differences. The vibe was different,” Kim said.

Change is hard, but it also serves as a motivating drive for human nature.

“Most immigrants believe strongly in the American Dream. That is what brings them here. I wish some young Americans had that dream, as much as immigrants do,” said Margaret Sands Orchowski, an author and a congressional correspondent of the U.S. Congress.

Whether it’s success measured in happiness, material possessions, or wealth, success comes to those who work hard. In a world of endless possibilities, everyone has an opportunity to achieve their dreams, but only if they are willing to take the chance.

“Have a goal set for five years, and if it doesn’t work, set another one for five years, and if that doesn’t work, keep going,” Pham said.