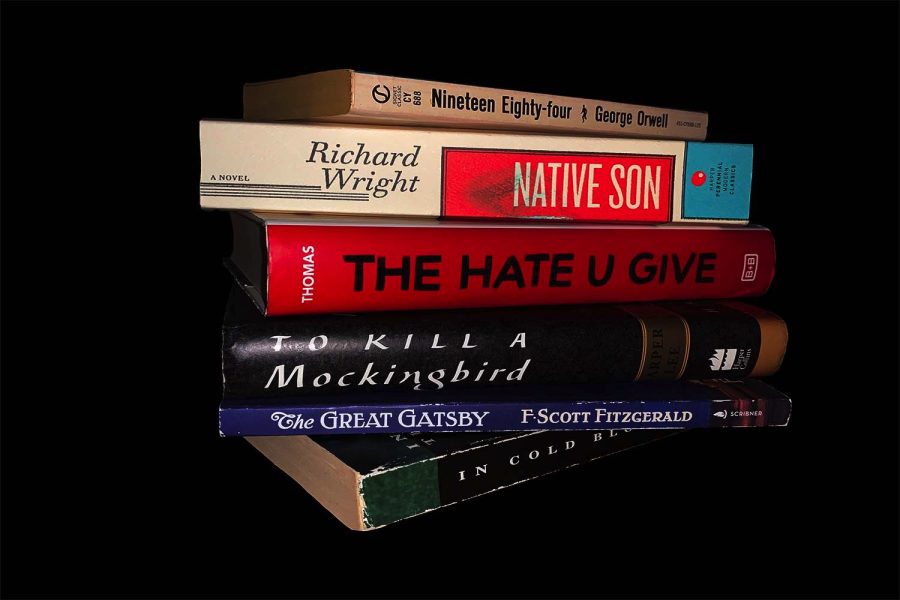

“To Kill A Mockingbird.” “Brave New World.” “Captain Underpants.” “Where’s Waldo.” These are four out of thousands of banned books in schools and libraries throughout America.

It may seem surprising, but many of the books read in school and as recreational reads have been banned or challenged books.

According to The Office of Intellectual Freedom, the most common reasons for books being banned include the material having “sexually explicit” content, “offensive language,” or “unsuited to any age group.”

Since 1982, the American Library Association has recorded 11,300 challenged books. To this day, book banning and challenges have not gone down calling into question the purpose and result of book banning. Jackie Farmer, the program officer at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, believes it brings the topic of freedom and understanding to light.

“It’s all about creating a larger conversation about preserving academic freedom and sparking intellectual curiosity and teaching people productive ways to respond to one another,” Farmer said. “Never have to agree with [a book], never have to support it, but having that kind of an understanding can help you pursue your greater causes and what you want to see in the world.”

Eye of the Beholder

Shotgun in one hand. “The Catcher in the Rye” in the other. Mark David Chapman awaits his arrest at the scene of the murder of famous singer, John Lennon.

“What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff–I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all,” reads Chapman.

Chapman quotes this passage from “The Catcher in the Rye” as his only justification for the murder of John Lennon. Claiming his inspiration for the murder came from the book and Holden Caulfield’s perception of society, Chapman displays the potential dangers of a book and supports its popular ban throughout libraries in America.

Books can have different interpretations for different readers. In Chapman’s case, he claims to have interpreted the book in a way that influenced the murder of John Lennon. Kathleen Kao believes books don’t pose a real threat for the majority of people.

“I think most rational people can separate what they’re reading: real life and their personal development. There’s that fear that whatever they’re learning or reading in a book will impact their personality, development, or thoughts of how they should act in society but I see books and literacy more as just escaping into a story and enjoying someone’s writing,” Kao said.

So, it’s unclear if Chapman was an out-of-the-ordinary character or if he was just like anyone else. Could anyone be swayed by a book as he had?

But alas, if Chapman is anything like Holden as he believed he was, we can’t take his word for anything he says. He’s just a phony.

Freedom to Read

Still, there is a difference between a book affecting a person like it had with Chapman and a book disagreeing or bothering someone.

“There’s a balance of [books] being educational versus something that might be contradictory to someone’s beliefs, something indecent, or something distasteful. It’s a balance between what you think is appropriate versus something being a literary work,” Kao said.

In 1975, after complaints from the Parents of New York United, the school board for the Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 in New York removed 11 books including “Black Boy” by Richard Wright, “Best Short Stories of Negro Writers” edited by Langston Hughes, and “The Naked Ape” by Desmond Morris from its schools’ libraries claiming they were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy.”

High school student Steven Pico, among other students, brought this action for declaratory and injunctive relief against the Board claiming that the Board’s actions denied students their rights under the First Amendment.

The case was argued before the Supreme Court which ruled in Pico’s favor in a 5-4 decision. The Board could not restrict the availability of books in its libraries simply because its members disagreed with the content.

At Carlmont, librarian Alice Laine talks about the selection of books in the school library.

“I adhere to selection criteria to choose materials that are appropriate for the social, educational, and intellectual development of students,” Laine said. “I do respect the rights of community members to hold their own beliefs and standards, but the mission of the Carlmont Library is to provide materials to all students that promote the love of reading and support the educational program.”

Adhering to community standards, books are not often banned at Carlmont. Rather, the selection of books chosen is based on appropriateness for a high school. Challenges in high schools also relate more to the curriculum.

“Texts that are read in class are chosen by teachers and are part of the class curriculum. I am not aware of any recent challenges to books in the library, but I do know that some parents have objected to the content of some of the novels being taught in English,” Laine said.

Despite where, why, or how an individual challenges a book, Farmer makes a point that the ideas and messages that books bring to the world can never go away.

“Ideas aren’t just going to go away because they’re banned,” Farmer said. “So, having that stuff out in the open and being able to point to who’s specifically supporting certain ideas and being able to engage openly or choose not to engage but observe and formulate your arguments and formulate your plan for change is important.”