There are aspects of female athletics that are often not talked about. In high school athletics, 80% of all coaches are male, and this sometimes means they don’t adequately discuss or understand female health, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

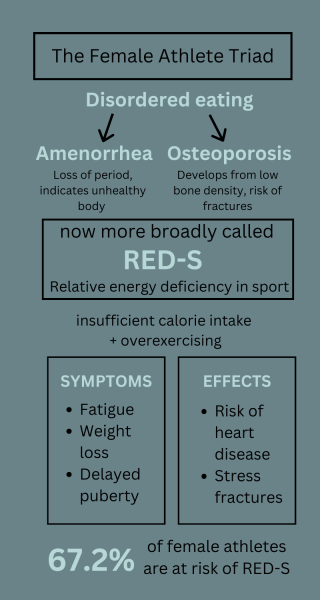

From a physical health perspective, Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S) is a big underlying issue that many sports teams do not have enough information about, according to The American College of Sports Medicine.

Overexercising and under-fueling cause RED-S, and in more serious cases, can take the form of an eating disorder. Symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, increased stress fractures, trouble staying warm, and, if left untreated, more serious health complications, according to the Boston Children’s Hospital.

Their website explains that RED-S affects more than 10% of athletes throughout their careers, and those in sports with a high emphasis on body type or weight are most at risk. This includes sports like wrestling, rowing, running, or dance.

Female athletes are at risk for a more specific combination of three disorders, called the female athlete triad. These common conditions are amenorrhea (loss of menstrual cycle), eating disorders, and osteoporosis.

They are often interrelated because disordered eating and restricted calorie intake often cause amenorrhea, an indication that something is physically wrong. Many female athletes do not realize this and accept it as a part of their sport, and continue restricting what they eat. This combination causes more brittle bones because people are not taking enough nutrients to maintain them, which leads to stress fractures and osteoporosis later in life, according to a researcher at Austin University in Texas.

“It can take months to recover from RED-S, and there can be long-term negative impacts on development and mental health. Sometimes the calorie restriction is intentional (disordered eating) and sometimes it’s from a lack of understanding about how much fuel your body needs, but regardless, the effects are serious,” said nutritionist Sarah Coble.

She added that food restriction and improper nutrition can take a serious mental health toll; physically it causes symptoms like brain fog and constant exhaustion, but it’s mentally difficult as well.

This combination of factors demonstrates the importance of RED-S education in the athletic community, according to Coble and an article from the National Library of Medicine.

She emphasized the importance of educating coaches and athletes on RED-S, in order to prevent it.

Taryn Sheehan, women’s cross country coach at Yale University, tries to implement her knowledge of the condition to improve her coaching.

“Education is key because most young athletes coming into our program have never been spoken to about the significance RED-S can have on their future health,” Sheehan said. “It makes it challenging at times to support an athlete’s athletic goal while also making sure we are making decisions for their long-term health.”

Sheehan tries to address topics like nutrition with her athletes with open dialogue on how they are feeling, and involving medical professionals if necessary.

“Most of our conversation stem around questions of ‘how do you feel?’ Typically I’ll ask things like ‘do you feel like your body is recovering’ ‘how is your sleep?’ ‘do you feel constantly inflamed and unable to recover?’ ‘are you craving coffee and a cookie at 3 p.m.?’” Sheehan said.

These questions can help Sheehan and the athletes understand where they might be falling short in their nutritional habits, and what to improve. She explained that they often remind athletes that as their training changes, their nutrition needs evolve and might need to be adjusted accordingly.

Former collegiate athlete Nicole Gavel, who went Division I for rowing at Harvard, explained how nutrition was addressed on her team.

“In high school, there wasn’t a ton of discussion around nutrition, but in college we definitely had people come and talk to us,” Gavel said.

“In high school, there wasn’t a ton of discussion around nutrition, but in college we definitely had people come and talk to us,” Gavel said.

In rowing, there are two categories; for openweight, anyone can participate, and the lightweight category has specific weight requirements, around 160 for men and 135 for women. Gavel said that she participated in the open-weight category for her team, and as a result, strict dieting was less of a focus.

“We would all go to the dining halls together and eat; rowing is a work sport, you’re out there burning a lot of calories in the cold environment, so you definitely want to refuel after you’ve been on the water for a couple hours,” Gavel said.

She explained that for those on her team participating in the lightweight category, nutrition was definitely a bigger challenge during training.

“There were definitely a few people that struggled with things as serious as eating disorders, maybe two people on my team,” Gavel said.

Similar to Sheehan, she emphasized the importance of education in these sports and involving a doctor or psychologist when necessary.

Sheehan explained that it’s important for athletes, coaches, and parents to know that they shouldn’t be afraid of “puberty” or changes that happen to an athlete’s body, or try to prevent them by restricting food.

“These are things that should be celebrated as signs of the body doing what it’s supposed to as a healthy growth and development. Rather than just overtraining to try and minimize these changes, we should be teaching these young runners how to be athletic, learning how to master fundamental movements and skills,” Sheehan said.

She said that understanding the importance of health and food freedom should also be stressed; certain types of food should not be feared despite the diet culture prevalent on social media. This often leads to struggles with body image among athletes, and more serious issues, as athletes are generally two to three times more likely to develop eating disorders than their peers.

Besides nutrition challenges, Gavel added her own advice to female athletes regarding other types of barriers.

“Don’t put limits on yourself, in terms of training and things like that. I had an idea throughout college of where I thought I could reach, and being able to train with men after college at this run club in California, made me realize I could go so much further than I thought,” Gavel said.

She explained that certain stereotypes about women being fragile or less competent, especially in athletics, exist. Growing up in spaces with male athletes, who don’t often have a stereotypically imposed limit of potential they can reach was really helpful to her, and she realized she could push herself more than she thought.

This went along with how she appreciated some of her high school coaches for pushing her and her team in a healthy way.

“He always pushed us to unlock this power and potential he knew we had, even if we didn’t see it, because we’d been told we were fragile or small, or that we were not as capable. I just wish I would have realized that message sooner, that sometimes the barriers you put up for yourself are fake,” Gavel said.