S*’s experimentation

His brother didn’t enjoy being on his ADHD medication. Bored and curious during his freshman year in quarantine, S* decided to take the pills himself.

What started as a cure for a quarantine slump turned into a tool for academic performance and recreation.

“I took Adderall today because I needed a good grade on both my finals. It’s fun to take it, and it feels good,” S* said. “I like taking Adderall because it makes me lock-in.”

Often used to treat patients with ADHD, Adderall allows for increased attention, concentration, and euphoria. However, taking the drug over its maximum prescription can leave users feeling the opposite of its desired effects—hence, a “comedown.”

“There have been times where I’ve taken the maximum prescribed dose and just sat down and done work for 5 hours and not gotten up. I’ve taken way more over the actual dose, and it just turned out to be an awful day,” S* said.

S* has had experiences with more than just Adderall. He uses drugs for recreation, including but not limited to nicotine, cannabis, and alcohol. There are other substances, like MDMA, that he hopes to continue his experimentation with.

“I usually cross it with alcohol, but the next time I’m doing a higher dose. It’s the best drug ever, and I’m definitely doing it again.” S* said.

S* did plenty of research on MDMA: he took into account dosage, proper use frequency, and fentanyl testing. He understood the drug’s potential health concerns, but he deemed the risk worthwhile.

“Something bad might happen, and I don’t want that. But honestly, I don’t see myself stopping,” S* said.

On the other hand, for S*, the downsides of substances like nicotine are not worth the temporary high. Based on the accessibility and addictive nature of the drug, S* is unsure whether quitting is a possibility.

“It is the most addicting thing ever — I quit for a month and like a week or two. Everyone says they’re going to quit eventually, and I hope that’s true, but it’s going to be around me all throughout college, so it will be hard,” S* said.

S*’s access to substances contributes to his use, but the burdens of being a teenager have also necessitated experimentation.

“High school is really long, and with the people that I’m friends with, there was no way we were going to get through it without touching that kind of stuff. It was inevitable,” S* said.

The solution

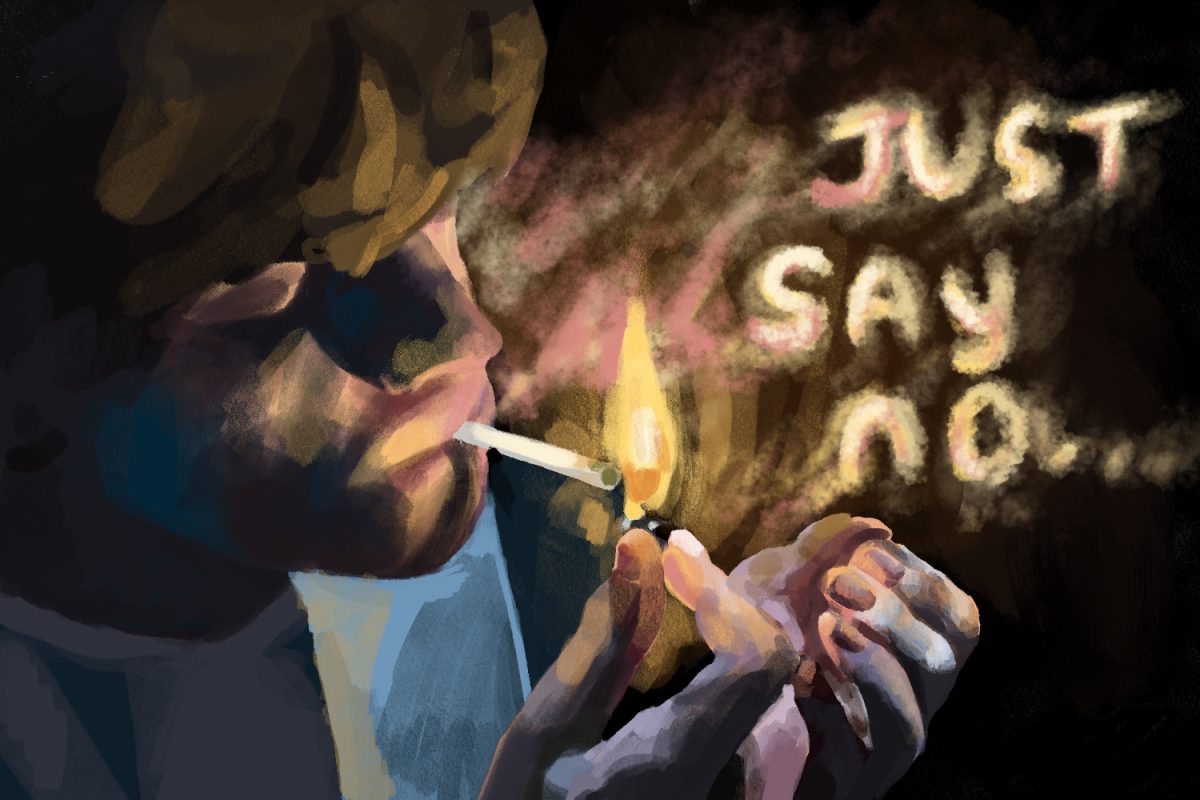

“Just say no.”

Originally an advertising campaign during the U.S.’s war on drugs, this phrase is currently used to discourage children from recreational drug use. While it is drilled into the drug education curriculum, studies and experience show that encouraging students to “just say no” may do more harm than good.

In reality, more than half of 12th graders reported alcohol use in the past year, and 30.7% of 12th graders reported cannabis use according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Similar to these teens, recovered addict and Ph.D. student Rahna Hashemi began her experimentation with alcohol and cannabis in her early years of high school.

“The exaggeration of the realities of drug use just made me more interested in them,” Hashemi said.

Hashemi had received a typical drug education characterized by scare tactics and oversimplifications.

“The war on drugs has infiltrated the mindset of school administrators and teachers. There’s no science that shows punishment helps kids. It’s this idea of, if we send a scary enough message then other people won’t do it, which just doesn’t work,” Hashemi said.

Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E) is a widely implemented school-based drug prevention curriculum in the U.S. that “gives kids the skills they need to avoid involvement in drugs, gangs, and violence.”

Reaching 1.2 million K -12 students annually, D.A.R.E emphasizes an evidence-based approach to reducing drug use. However, a PBS study reported that the program obtained limited effects on drug use because its curriculum decayed over time. D.A.R.E’s lack of positive results points to the need for an alternative approach.

“We promote misinformation and exaggerations about drugs in the place of honest conversations, and it’s failing everybody,” Hashemi said.

The need for open communication presents itself in the relationships between adults and teenagers. While authority figures tend to punish children for drug experimentation and use, this solution may be less effective than simply having a discussion about safe use.

“At home, having candid talks about real-life experiences, without resorting to scare tactics, can be enlightening. Additionally, insights from professionals like doctors or counselors can offer a reality check and deepen their understanding,” said Dr. Anuraag Ravi Kumar, a Physician at the Eisenhower Medical Center.

Having constructive conversations may be more likely to prevent addiction, which is defined as “a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences.”

“What negative consequences like punishment, stigma, or isolation do is they further dislocate you from a community, and you become more reliant on drugs to fill a void,” Hashemi said.

In fact, a study done by the University of Florida found that exclusionary discipline practices like suspensions and expulsions isolate students and create more opportunities for problematic behaviors.

To find a more proactive method for drug education, Hashemi looked at historical teachings.

“In the early 70s, there were a couple of years where the default was not ‘just saying no’ and abstinence, but science-based education about drugs. But then, with the advent of the war on drugs, that got squashed,” Hashemi said. “So I was like, ‘What if I brought that back?’”

Contrasting the mainstream drug prevention perspective, Hashemi started the nation’s first harm reduction education program in 2016: Know Drugs. Her mission is “to combat the silence that stigmatizes teens, promote responsible drug use, prevent teen overdoses, and foster informed discussions by providing accessible education.”

Rather than the standard curriculum, which focuses on abstinence, KnowDrugs works with schools to have open discussions about substance use and addiction.

“Young patients often feel more at ease discussing their substance use when they know the conversation is confidential and without judgment,” Harris said.

Using research and customization to form a realistic outlook on teen drug use, KnowDrugs creates an informed curriculum to keep students of all ages safe.

“Instead of just telling you that you are at risk for overdose for using these drugs, we also tell you how to identify your dose, what to do in case of an overdose, and also how to prevent an overdose if you choose to consume a drug,” Hashemi said.

Hashemi sees drugs as a problem plaguing many teenagers today but chooses to acknowledge the possibility of experimentation rather than suppress the conversation altogether.

“Whatever it is, a door of communication needs to be open. You need to meet teens where they’re at, but you also need to hold boundaries for safety and accountability,” Hashemi said.

*In accordance with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy, the name of the subject has been changed to preserve the subject’s identity.