Intro

Vegetarianism, veganism, pescetarianism; how about entomophagy? Instead of subtracting from your diet, what if you could add? It’s a decision that could start a swarm of positive change for yourself, for the people, and for the Earth.

This may sound like chirping in your ears. But, I urge you to adjust that antenna, tune in, and prepare the residence of your abdomen. For you may just become an entomophagist: a person who eats insects.

Current situation

Remember, global warming results from the greenhouse gasses we humans produce. That includes carbon dioxide, methane, ozone, refrigerants, and more. According to the University of California, agriculture and land make up 20.4%, a fifth, of all greenhouse gas emissions. Largely a consequence of deforestation and raising livestock.

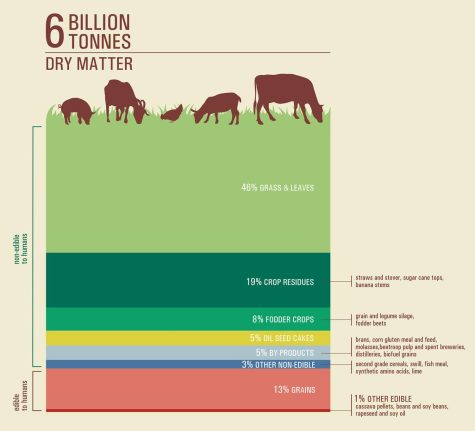

Moreover, a staggering 80% of all farmland is used to feed cattle, pigs, and poultry. This is compounded by the fact that the world’s population is estimated to swell to 9.1 billion by 2050, according to the FAO (Food and Health Organization). This would require agriculture to grow by 70%, meaning more deforestation and more livestock—two things the Earth cannot handle.

Nowadays, many choose to abstain from meat or animal products in general—going vegetarian and vegan. However, one can still make a significant impact if one simply lowers their meat intake. A study conducted in Argentina found that halving one’s meat consumption can reduce their emissions by 20 to 30%. And that is where bugs come in. They are rich in protein, making them an alternative protein source to traditional meats.

World Hunger

Southern Madagascar is experiencing the fourth consecutive year of extreme drought. Harvests have failed, and food stocks are running low. Estimates by Unicef say that 1.14 million people are food insecure, and as of July 2021, over half a million children under the age of 5 are malnourished.

Families are forced to look in the jungles and hunt for lemurs. Seeing as 90% of these lemur species are threatened or endangered, scientists have come together to help the people and protect the animals of Madagascar.

Scientists have turned to crickets, which are 65% protein and rich in minerals. Valala Farms, in partnership with the California Academy of Sciences and Madagascar Biodiversity Centre, have set up farms that raise Madagascan field crickets and have made them an accessible food source for the people. In the near future, it is Valala Farms’s goal to upscale and supply enough protein for all Madagascan children.

Like Madagascar, global warming will continue to devastate communities across the world. Drought causes crop failure, and crop failure causes famine. Bugs may be the untapped food source that can provide for the hungry.

Environment

In another experiment in Madagascar, researchers learned of a bug called sakondry. For some Madagascan villages, they were regularly consumed along with pork and chicken. Often, the sakondry was not easy to find, and thus the villagers had to hunt lemurs. The researchers discovered that the insect thrived on a native bean plant, which they encouraged villagers to plant around their village. According to Time, the poaching of lemurs in that area decreased by 30 to 50% within two years.

If we zoom out, it is clear that widespread entomophagy can have a major impact. Insect farming takes less space, less food, less water, and produces less greenhouse gas emissions. On average, it takes eight kilograms of feed and 22,000 liters of water to produce one kilogram of beef. This is much more than the two kilograms of feed and 850 liters of water it takes to produce a kilogram of cricket meat, according to Business Insider. On top of that, crickets are estimated to produce one-eightieth of the methane produced by cattle.

If insects one day become a staple protein along with beef, pork, and poultry worldwide, this Earth could be a better place.

History

On paper, the potential of entomophagy is almost mouthwatering, but it isn’t for one reason: the simple fact that bugs are gross. With their many legs, beady eyes, and twitching antennae, many bugs are frightening to be in the same room with, so who could imagine eating them. The thought of munching on these will evoke the heebie-jeebies out of most everyone.

This universal disgust towards insects emerged tens of thousands of years ago. As hunter-gatherers, before the dawn of agriculture and complex civilizations, our ancestors foraged for plants, hunted animals, and scavenged for insects. Believe it or not, those six-legged critters were staples in our diet, delicacies even.

According to TED-Ed, our deep-rooted “disgust” of bugs began around 10,000 B.C., when people began settling in the Fertile Crescent. When our ancestors learned to domesticate animals and cultivate crops, we started to see insects started as pests that ruined our harvest, and as Western civilization continued to urbanize, those views only strengthened.

However, insects never strayed far from the dinner menu. Many countries across Africa and a few in Asia still regularly eat insects. It does not stop there. If you read the ingredients of snacks like M&M’s or skittles, you may find an ingredient called Red 40 or cochineal extract. This ingredient contains Carminic acid, the specific chemical capable of producing the bright red color. Carminic acid can only be found in the scales of the tiny 5-millimeter Cochineal beetle. These bugs are sun-dried, crushed, and soaked in an alcohol solution. According to Live Science, 70,000 beetles go into one pound of Red 40.

Furthermore, creepy-crawlies can end up in our food when they are not supposed to, and the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has guidelines for these occasions:

- Ground cinnamon can have up to 400 insect fragments per 50 grams.

- Noodle products can have an average of 225 insect parts per 225 grams.

- Flour can have 75 parts per 50 grams.

The list goes on and on.

So, we may no longer “eat” bugs in the traditional sense like stakes or chips, but if you look hard enough, they are there, occupying the nooks and crannies of your food packages and ingredient lists.

Truth

For all these noble reasons, I personally could not imagine ever eating bugs. So, I took it upon myself to take the leap of faith. First, I tested out cricket brownies from a company called Cricket Flours. It tasted like brownies, just regular brownies, and the knowledge that you ate crushed crickets.

Then, I tried some whole roasted crickets; they came in with antennae, wings, legs, and everything else. It took a while to work up the courage, but I was able to take a bite. These were quite tasty. The crickets were sprinkled with a power that gave most of the flavor. The texture was crunchy and flaky, like a combination of kettle corn and wafers. Overall, it was a pretty munchable snack when you avoided staring into those eyes that stared right back. If the -ick factor is overcome, I could see roasted crickets finding their way next to Lays on the grocery shelves in the future.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9wgfraQp3M[/embedyt]

A similar situation has happened before. When settlers first started arriving in North America, Lobsters had a nickname; cockroaches of the sea. According to Business Insider, They were used as fertilizer, fish bait, and fed to inmates and enslaved people. It was a far cry from the delicacy we know and love today. This all changed when railway companies started serving canned lobsters to passengers in the mid-1800s when people started enjoying the taste. Thereafter, lobster popularity skyrocketed, and the rest is history.

Impact

It is hard to express the potential impact entomophagy can have in the future. Bugs are already a linchpin in feeding the world as it is. Estimates by the FAO suggest that today, 2 billion people eat bugs in their traditional diets, and over 1,400 different species of insects are eaten. Once the western nations of Europe and North America catch on to this untapped resource, we may see some major changes.