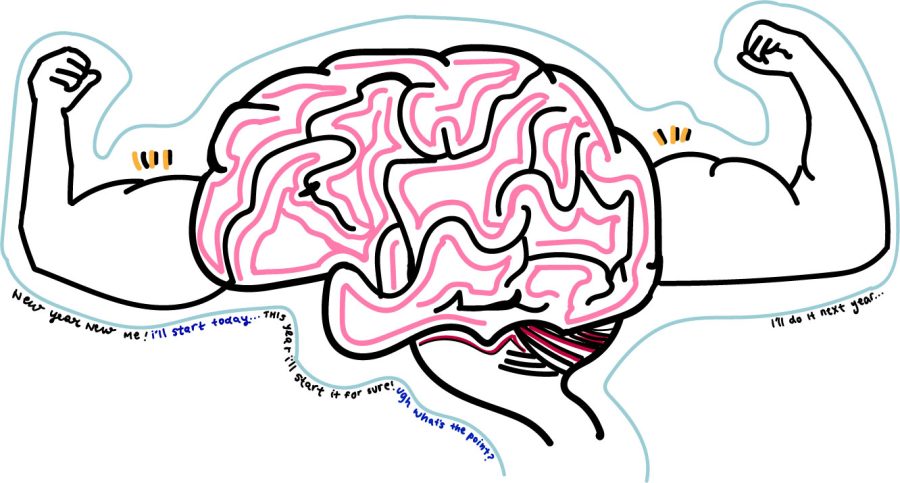

This year, I’m going to stop procrastinating.

Sound familiar? Most students repeat the classic saying as they enter the new year.

Setting a New Year’s resolution is generally a common practice across the globe, where people strive to bring fresh habits.

“Life is filled with a variety of transitions and those transitions, [such as the new year], offer an opportunity to engage with a new set of goals,” said Nilam Ram, a psychology professor at Stanford University.

Millions of Americans share a hopeful outlook. Students aim for better grades, adults aim to save money, and individuals across the country are scrambling to promise themselves improvement, seeking the gratitude that a clean slate will bring.

Until it doesn’t. About 80% of Americans fail to follow through on their resolutions. It’s the same story every year, where statistically, the citizens’ goals end up falling through.

In many scenarios, the goals had already failed before the year began. The resolution’s creation has already bitten the person in the back.

“People find [resolutions] difficult to keep because they’re general ‘do-your-best’ goals which have been found quite useless,” said Seppo E. Iso-Ahola, a psychologist at the University of Maryland. “From a motivational standpoint, goals have to be proximal, specific, hard, but attainable.”

Besides the mediocre goal-creating skills, there’s also a scientific explanation for the personal resolution failures. The patterns of a psychological phenomenon known as false-hope syndrome loom over the optimism that the new year brings.

“False-hope syndrome relates to a psychological concept of overconfidence, and it’s sort of innate in everybody,” said James Bohac, a psychology teacher at Carlmont High School. “It’s hard for anyone to know what their own efficacy is.”

When humans deceive themselves into believing that self-change is simple, they establish unreasonable expectations for themselves. The eventual effect is a loss of confidence when reality sets in, and as a result, the urge to achieve the objective fizzles out.

The research conducted by Bohac and his students suggests that people choose to make objectives in the first place because of the notion presented in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The hierarchy provokes the mind to set goals; once it’s coupled with false-hope syndrome, the internal expectations towards that goal build upwards.

“According to [the pyramid], people strive for self-actualization and to feel better about themselves,” Bohac said. “Once they realize they can’t exactly achieve it, whether it’s because they lack the ability or another factor, the human ego will crash.”

Apart from the issue with the objective itself, human motivation tends to wane as the year progresses and individuals face the realities of the new year. Iso-Ahola emphasizes that following through on one’s vows to change is challenging since it requires the individual to leave one’s comfort zone.

“It’s an idealization. It’s difficult to go out of [one’s] way to create new habits but easy to follow old ones,” Iso-Ahola said.

The mind, not the person’s conscious action, is the culprit for the inability to leave one’s comfort zone. Subconsciously, the human mind tunes out signs of misery and instead yearns for the comfort of habits to ensure emotional serenity.

“Actually, 98% of the time, our cognitive and behavioral functioning is at the nonconscious level because people seek to avoid cognitive and behavioral strain. People subconsciously search for the path with least resistance,” Iso-Ahola said.

People lose motivation, the goal diminishes, and yet the cycle still repeats the following year once the illusion of potential self-fulfillment lures people. Maslow’s theory strikes again, and an individual will murmur another unattainable goal to themselves, despite the previous year’s failure.

However, there are ways to escape the repetitive defeat using techniques recommended by experts.

“An important psychological tool is using ‘implementation intentions,’ which are specific action plans that include ‘if-then’ contingencies,” Iso-Ahola said. “An example could be ‘[I’ll be] doing it tomorrow at 6 am, where I’ll be running outside with my friend John.’”

Instead of getting caught up in the big picture, Iso Ahola recommends setting specific goals and breaking down the resolution step-by-step.

Avoiding the trap of false-hope syndrome means taking it slow, which creates maximum efficiency once the human mind feels the satisfactory taste of accomplishment along the way.

“It is about lining up the little goals into the big goals – checking the near-term goals off on the way to achieving the big goal,” Ram said.

When creating a game plan towards the resolution, specifying goals and taking it slowly are strategies. To achieve the goal itself, nurturing human motivation with a supportive environment is also a psychological tip.

“It’s helpful to use the human mind’s social intelligence. Psychologists discovered that everything we do is based upon everything around us, so having social support naturally pushes people to achieve their goals,” Bohac said.

Understanding psychological traps allow humans to avoid them and instead maximize their brains to accomplish what they aimed for in their resolutions.

“Concentrate on changing the things that can be controlled,” Ram said. “Keep pushing forward!”