Winston Churchill famously remarked that history is written by the victors, a truth that reflects the complexities of America’s historical narratives.

The past of the United States is marked by the oppression of many marginalized groups — a narrative that the government has often obscured.

In recent years, some states have made efforts to acknowledge historical wrongdoings and bring awareness to the nation’s contemptible past. Seventeen states have now replaced Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day to address the controversial legacy of Christopher Columbus, largely due to the persisting impact of colonization on Indigenous communities across the nation.

“Over the years, especially since I was in high school, people have become more generally aware of Native American history. Textbooks now have much more Native American content, but they are not as complete since they aren’t for Native American history courses. It wasn’t always the case to acknowledge marginalized groups,” said David Gomez, a U.S. History teacher who has been at Carlmont High School for 37 years.

As part of these efforts, on Sept. 27 — California Native American Day — Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill requiring public schools across the state to provide instruction on the mistreatment and contributions of Native Americans during the period of Spanish colonization and the California gold rush.

“Each subject has state standards, and with the current legislation, they’ll have to revise those standards to include Native American history and ensure that various topics and people are covered properly,” Gomez said.

Indigenous descendants voice inequities in historical education

Many people in California view the law, which targets elementary, middle, and high school students, as a meaningful step forward in recognizing the contributions of the Indigenous peoples who came before them.

However, many individuals of Native American ancestry remain distrustful of the state and skeptical about the true extent of change this law will bring — some express concerns over whether it will lead to significant long-term reforms.

“I think this is only the first step in acknowledging the crimes committed against Native Americans. We don’t talk about what happened after the murder of millions of Indigenous people. It’s often seen as something passive, only something that happened in the past, and we overlook what’s happening now,” said Chloe Harris, a junior at Carlmont High School.

Harris is part Navajo, or Diné, as they call themselves, a Southwestern people with the largest reservation in the U.S. More specifically, she belongs to the Todích’íí’nii (Bitter Water Clan), one of the original lineages in the Navajo tribe.

She traces her lineage primarily through her grandmother, who experienced firsthand various transgressions by the U.S. government, including the Catholic boarding schools placed on reservations like those of the Navajo, where many of her grandmother’s cousins and siblings died.

Because Indigenous cultures are still being impacted today, it’s critical for schools to address ongoing issues so that students are fully aware of how Native American communities continue to be affected.

“Many Native Americans on reservations live in poverty, and Indigenous peoples don’t have access to good healthcare and education. They are not getting the full truth,” Harris said.

Harris’ concerns about the disparity in how Native American history is currently taught are echoed by Ash Thompson*, an individual of primarily Cherokee descent who lives in the upper regions of Utah.

According to Thompson, schools must start portraying historical figures accurately, citing that with proper instruction, people might be able to recognize ongoing issues and address their biases.

“Although I don’t expect a gory and awful, long course on how my people were treated, facts should be given objectively, and the responsible people, such as Andrew Jackson and General Custer, should be named and listed for their actions. It’s not a hot topic or something that should be stepped around. It is history, and those who do not understand or know history are bound to repeat it,” Thompson said.

The high school Thompson attended only mildly addressed the history of Native Americans, with certain teachers choosing to incorporate additional lessons relevant to their region. For instance, one of their teachers addressed the Bear River Massacre, a slaughter that took place on Jan. 29, 1863, when the United States Army attacked a Shoshone encampment.

“Although, to my understanding, this was not a required subject. It was simply that one history teacher who decided to include it as part of his history lesson,” Thompson said.

The delay in the nation’s desire to address past injustices likely stems from a history of neglect toward Native American communities.

“There’s so much the government wants to hide, and we briefly cover what happened in the reservation schools, where some of my grandmother’s siblings and others in the community would die because they were put in boxes or left outside in the heat and treated like animals,” Harris said.

According to Harris, the government is ashamed of its past and seeks to conceal this aspect of history, not wanting people to realize that it isn’t returning what was taken from Native Americans.

“The government knows it was wrong, but they don’t want to confront America’s ugly history or acknowledge that they’ve destroyed so many Native American cultures,” Harris said.

Educating history with Indigenous guidance

Newsom’s new legislature mandates that the state Department of Education must consult with tribes when updating its history and social studies curriculum framework starting at the beginning of next year. This initiative reflects an ongoing movement across various regions of the state to create curricula that accurately represent Indigenous cultures.

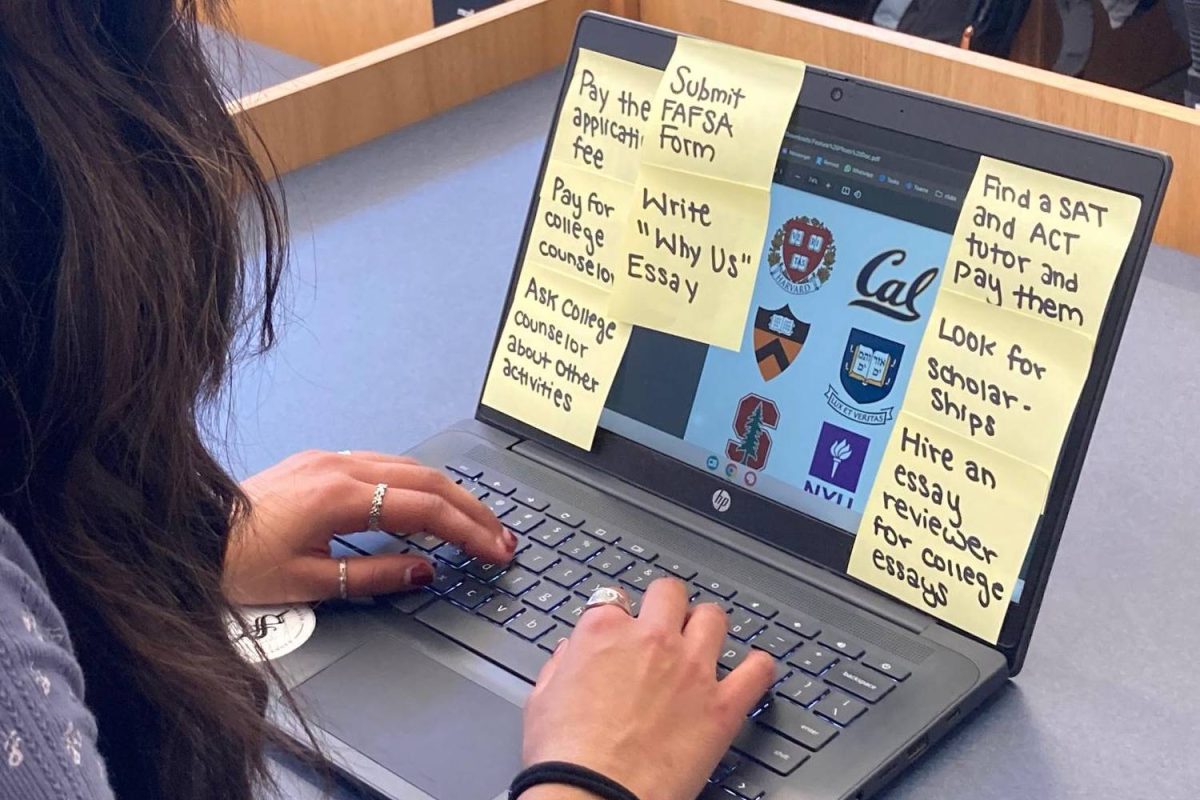

However, due to the gradual nature of how legislation is implemented, it may take years before substantial changes occur. Additionally, some individuals remain skeptical about the state’s capacity to enact proper reforms regarding Native American affairs.

Lloyd Mathiesen has served as the tribal chairman for the Chicken Ranch Rancheria Me-Wuk Indians of California for 13 of the last 16 years, spending the last eight years consecutively in his role.

Once thriving as a moderate-sized community of Me-Wuk natives in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Tuolumne County, the people of Chicken Ranch Rancheria have witnessed their historical territory shrink over the past 150 years. The expansion of mining and logging operations, along with the purchase of repatriated land by western settlers, has reduced their ancestral land to a mere 2.85 acres.

Mathiesen’s distrust in the new legislature’s ability to implement change stems from the tribe’s tumultuous history with the state of California and Gov. Newsom. In 1985, the tribe gained federal recognition as an autonomous Native American Tribe of California after being unrecognized by the state government since 1963.

While the tribe has since thrived, it remains relatively small, with only 44 members. Mathiesen attributes their small size to the loss of land caused by the state, which led many to leave, leaving only certain tribal members behind.

Mathiesen expressed skepticism about Newsom’s ability to enact real change due to the tribe’s historical conflict with the state. This history includes a lawsuit involving the Chicken Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California and four other Native American tribes. They successfully challenged Newsom over bad faith negotiations, in which the state demanded extensive environmental regulations and additional requirements during negotiations to renew their casino operation contracts.

“I wouldn’t expect anything to happen in the next four to six years, and I’d be lucky if it does within that time frame. This governor talks a lot; he says one thing out of one side of his mouth and something completely different from the other,” Mathiesen said. “I genuinely believe this is just another empty gesture. They often pass measures they have no intention of implementing, just to silence people.”

While he believes it’s a positive step for the state to establish this standard, he restrains his excitement. According to Mathiesen, the process often takes an incredibly long time once things are in the government’s hands.

However, the Me-Wuk Native Americans are developing their own alternative by working closely with their local government to implement changes directly into the district’s education system. This is similar to efforts made by many other tribes across California in their respective regions.

“Prior to this bill, we’ve been working with the school superintendent for the past year. We have three schools that want to adopt the curriculum, and we’re trying to determine the right age levels to introduce it. Much of the history of Native Americans in California is filled with a lot of death and massacres,” Mathiesen said.

With their specific curriculum, Mathiesen and his tribe are creating a comprehensive approach that includes elements from their tribe and other local tribes in Tuolumne County.

“We want to teach about our history, but also all of Californian history, including the truth about the missions, the mining, and how California became structured,” Mathiesen said.

In particular, the Me-Wuk Indians, along with several other tribes, are advocating for the inclusion of American Genocide by Benjamin Madley in school curricula at both the state and local levels. This text, which Yale University also uses, provides a comprehensive account of the state-sanctioned mass murder of California Native Americans.

Mathiesen expressed hope for Californian tribes collaborating with their local governments, believing it to be more effective and faster than state-mandated reform for the education system.

“I am excited, though, that a lot of tribes are working with their local regions. We’re not the first; I hope we are nowhere near the last. We’ve talked with tribes in Eureka, Ukiah, and several others down south to communicate with them on how they worked with their local government to achieve this. I’m glad the state is trying to do this, but I know it won’t happen within this decade,” Mathiesen said.

Similar to the Me-Wuk, the San Mateo County History Museum has been collaborating with local tribes to portray Native American history across its various sites accurately. This highlights that, despite recent legislation, some institutions have been making efforts for years to incorporate Native American history into youth education properly.

The museum offers a robust program for schools, with many regional public elementary schools utilizing either the San Mateo County History Museum, the Sanchez Adobe site, or the Woodside Store for field trips that provide hands-on, interactive experiences. Each year, they engage around 20,000 students and their chaperones.

Uniquely, the Sanchez Adobe site — a 5-acre property in Pacifica — features a modern interpretation of the Native Americans known as the Aramai, who belonged to the Ramaytush language group and once formed part of a village community called Pruristac.

Unlike the museum’s more general approach to the Ohlone people, the Sanchez Adobe site focuses on the rich experiences of the Aramai over the past 500 years.

“We hired Ohlone muralists to help create scenes that would’ve been at that site, and their work has been borrowed numerous times because it’s so accurate and well done. The background is the centerpiece, but kids can also experience what it’s like making baskets and other things reminiscent of the experience of Californian Indians,” said Mitch Postel, the director of the museum for the past 40 years, who oversees all three educational sites.

Additionally, Postel expressed his pride in the exhibits at the Sanchez Adobe, as they collaborated with local Native Americans in ways they never had before. This included a meaningful partnership with Jonathan Cordero, who demonstrated his family lineage tracing back to the Indigenous people who lived in Pacifica.

“He’s been gracious enough to attend some of our events, conduct lectures at the Sanchez Adobe, and assist us with interpretive issues. His guidance has helped us be as sensitive as possible to the feelings of Native people here now,” Postel said.

A token holiday

As Columbus Day approaches, now recognized as Indigenous Peoples’ Day in some states, Native Americans have mixed feelings about the holiday.

For some, like Thompson, Indigenous Peoples’ Day serves to acknowledge the ongoing existence of Indigenous cultures, even as they face the threat of decline and assimilation.

“I was unaware that Columbus Day was being replaced by Indigenous Peoples’ Day or Awareness Day, but I absolutely love that. It will help many people understand that their pain and needs are being addressed and allow us to regard history for what it really is,” Thompson said.

Others, however, see it as a tokenistic gesture lacking genuine progress. According to Harris, even with the shift from Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day, the focus still remains around Columbus, marking the day he supposedly “discovered” Indigenous peoples who had already lived there for thousands of years.

Harris believes that even if the change is intended to raise awareness, people must understand the significance of what they are celebrating.

“I don’t see the need to replace it; I would rather just get rid of it. What would we be celebrating for the Indigenous peoples? The day that their lives changed forever and everything started to be taken from them? I don’t see the need to have it if it is only that day in name and not in action,” Harris said.

Sharing her sentiment, Mathiesen expressed his doubt about the impact of changing the holiday’s name.

“Our local county decided to declare Native American Day, and they asked me to come. For the last two years, I’ve declined to go because I told them three years ago, ‘If I’m just gonna be your token Indian and help you declare this without anything meaningful that comes from it, I’m not going to participate,’” Mathiesen said.

According to Mathiesen, genuine awareness would come from efforts on Indigenous Peoples’ Day to educate students about the lives of local Native American tribes today.

“How about we get the schools together, and the kids can come to our reservations to see how actual Native American governments operate in today’s world? That’s something tangible — something deeper than just putting on a stamp saying, ‘We did this; we checked the box. We said it was Indigenous Peoples’ Day,’” Mathiesen said.

*This source’s name is changed to protect them from social consequences. For more information on Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing, check out Scot Scoop’s Anonymous Sourcing Policy.