“Would you like to be my sugar baby $700 weekly allowance for you?” a Carlmont senior read from her Instagram direct messages. “You interested in the offer dear?”

There is no concrete definition for a “sugar baby” and “sugar daddy” relationship. “Sugar babying” is commonly seen as an interaction in which a younger person gets paid in money or materials by an older person for their company. It is not necessarily sexual, more a desire to just have someone to talk to. Sugar babying is like a revamped version of a “gold-digger.”

One Carlmont senior, Addison Baird*, had her own experience with a few sugar daddies.

“A lot of the sugar daddies reached out to me through Twitter DMs. I always used a different name, age, and location, and they never really questioned it because most of these people are in it to scam young kids,” Baird said.

She noted that the entire system of sugar babying leads to a lot of scams.

“I think a lot of people immediately fall for the trick. They say you need to pay them a fee in order to enter their ‘system’ and prove that you’re real. I never would pay them, however, I know people that did and they got scammed of their money,” Baird said.

While technically, it does not have to be a sexual interaction, sugar babying is often on the same plane as prostitution and sex trafficking. A study from sociologist Maren Scull, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Denver, discovered that about 60% of sugar babies had sex with their benefactors.

While technically, it does not have to be a sexual interaction, sugar babying is often on the same plane as prostitution and sex trafficking. A study from sociologist Maren Scull, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Denver, discovered that about 60% of sugar babies had sex with their benefactors.

The state government defines sex trafficking as such: “Sex trafficking encompasses the range of activities involved when a trafficker uses force, fraud, or coercion to compel another person to engage in a commercial sex act or causes a child to engage in a commercial sex act.”

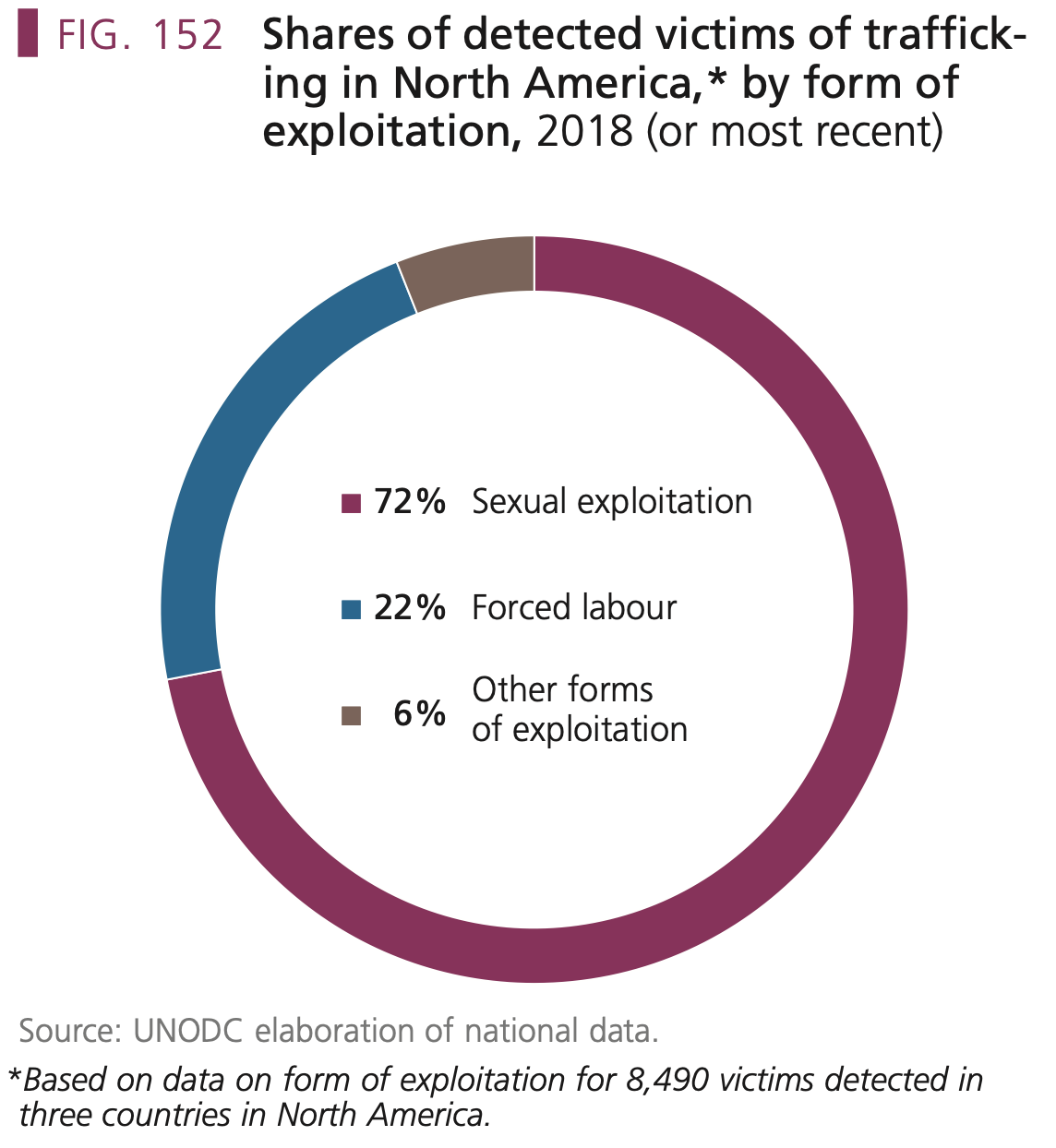

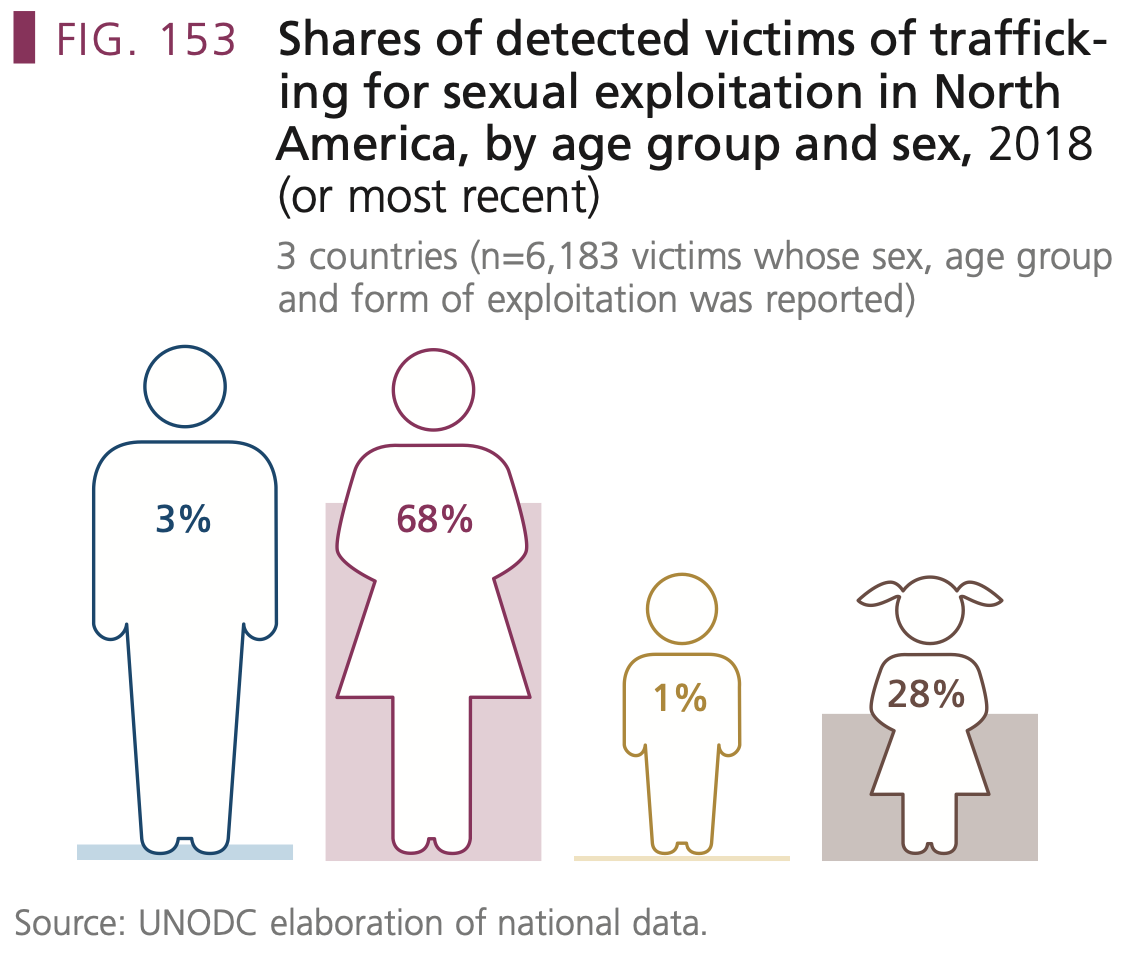

The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons in 2020 notes: “victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation are normally promised a job unrelated to sexual activities.” A sugar baby relationship can quickly escalate into a sex trafficking case. According to that same report, 72% of all trafficking cases in North America were sexual exploitation, and from that, 96% were of women.

Much like Baird, another Carlmont senior found herself wrapped up in another form of online sexual exploitation. She sold pictures of her feet for about two years.

“A user I didn’t recognize added me on Snapchat and I didn’t think much of it so I added them back. They started texting me and explained that if I sent photos of my feet, they would pay me $5 a photo,” Christine Johnson* said. “I was with my friends and we thought it was funny so I accepted. I honestly thought it was a scam so I was totally shocked when they sent me $20.”

She started in freshman year when she was 15 and continued until junior year. She collected payments on Venmo and sent pictures when the user would ask. However, it took a turn for the worse.

“I stopped last year because the user started getting really disrespectful. If I said no to sending photos, they would get angry and it made me uncomfortable,” Johnson said.

While sexual exploitation in these forms is typically viewed in a negative manner, everyone has their own valid opinions and reasons to agree to these requests.

“Even though my face was never in any of the feet pics, I felt weird sending a stranger photos of any kind,” Johnson said.

*These names were changed by the authors to ensure anonymity for the sources that were interviewed due to fear of physical or emotional harm, in accordance with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy.