On a Wednesday afternoon, Vyas Kepler arrived at his high school swim practice. The Carlmont High School senior greeted a teammate and rushed to the pool, goggles in hand, when something made him stop short.

The pool gates were locked. Confused, Kepler looked around. Besides his one teammate, it was empty. Something was wrong.

After waiting for a couple of minutes, they called another swimmer and learned that their coach had sent out an email. Their swim pod was shut down for the day, and practice was canceled. No one knew why.

A wave of panic and anxiety surrounded the group. Was there a COVID-19 case? Did something happen? Were they not being safe enough?

Then, after three days, the pod suddenly reopened without any explanation. Everyone went to practice, expecting answers. They got none.

“The one email we received from our coach wasn’t very transparent… it didn’t say why [practice] was canceled at all,” Kepler said.

Kepler’s experience isn’t unique in San Mateo County. Many local schools are not communicating well.

In many school districts in the County, the administrators seem content with their protocols. They take the required precautions and follow district procedures.

Jeff Boise, the principal at Capuchino High School in the San Mateo Union High School District (SMUHSD), expressed his satisfaction with his district’s policies.

“From my perspective, we have had a very effective and consistent set of practices in response to COVID-19 both at [Capuchino High School] and throughout the [SMUHSD]. This includes areas such as health, safety, training, and communications,” Boise said.

Representatives at the Sequoia Union High School District (SUHSD) have voiced similar sentiments.

“We follow all the appropriate guidelines from the [Center for Disease Control and Prevention] as well as strictly follow HIPAA guidelines. I can assure you that if anyone was identified as possibly being exposed, they were notified,” said Samantha Gingher, the health aide at Carlmont High School.

However, the incident with the varsity swimming team suggests otherwise.

“We never heard anything from the District or Carlmont administration,” said Kayla Hogan, a Carlmont junior and swimmer. “The sudden cancellation without explanations caused a lot of confusion and anxiety, as we didn’t know what the situation was.”

This lack of transparency between the schools and the community has caused further confusion. In the absence of information, many people are left unknowledgeable about the situation. Rumors have popped up, but nothing is concrete and a climate of uncertainty remains.

“I’ve heard rumors about exposures that turned out to be incorrect,” said Paige Perez, a Carlmont parent. “I heard one very serious one regarding a high school girl that had supposedly given COVID-19 to her dad and younger brother, causing both to be hospitalized due to the severity of the cases. However, I knew the girl personally, and after doing some digging found it to be extremely false.”

Many students, parents, and staff alike seem to feel there is a lack of sufficient information coming from the school and district.

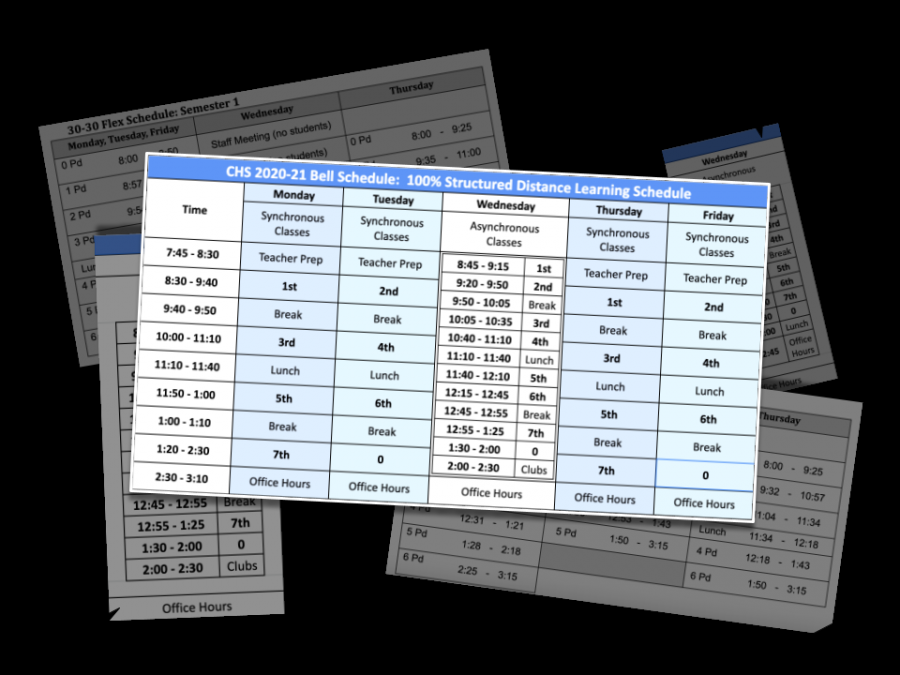

“We need to have several different ways: email, Canvas message, posts on the website, written communication, and videos of people explaining things. Unfortunately, communication is often incomplete and confusing. Then there are contradictory messages that follow those, so there seems to be a consistent level of confusion,” said a SUHSD teacher who, in line with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy, preferred not to be named to avoid any professional repercussions.

Outside of those directly impacted, the rest of the community is often left in the dark with no knowledge of cases, closures of pods, or anything related to school activities.

“We have to be careful what we put out there as far as confidentiality, so we don’t put specific names out when we have students that are reported as being positive,” Carlmont Principal Ralph Crame said. “If students are not coming to school in one of our cohorts, whether it be an athletic pod or one of our support pods, we don’t inform people that a student has tested positive for COVID.”

The same can be said for other local school districts in the area.

Leila Kane*, a junior at Burlingame High School who preferred to remain anonymous to avoid consequences or complaints for speaking out, has received no information regarding exposures or cases at her school.

“My family and I haven’t received any information from my school, and I haven’t heard anything from my friends about any information,” Kane said.

Kane, however, knows there’s information to be shared. Her boyfriend, who also attends Burlingame High School, had an elder sibling test positive for COVID-19, exposing both of them.

Many districts claim they withhold information because of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1966 (HIPAA) and its implementing regulations that protect patient privacy by prohibiting certain uses and disclosures of health information.

“There are many HIPAA regulations around letting people know that other people have tested positive,” Gingher said when asked about the confidentiality of cases.

However, Gingher and other school officials are not entirely correct. HIPAA does not apply to most schools, as they do not meet the definition of a “covered entity“ under HIPAA when they receive medical information reported by parents, students, or staff.

“People commonly misunderstand the extent of its applicability,” said Deborah Sim, Senior Vice President, General Counsel, and Head of U.S. Site Operations at Vifor Pharma, Inc.** “The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1966 (HIPAA) is often referenced generally in relation to disclosures of medical information; however, HIPAA only applies to covered entities as defined under the law.”

A different law, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), more likely governs the confidentiality of student records. The U.S. Department of Education defines FERPA as “a federal law that affords parents the right to have access to their children’s education records, the right to seek to have the records amended, and the right to have some control over the disclosure of personally identifiable information from the education records.”

Despite these protections, a section in FERPA could allow schools to distribute COVID-19 data.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, “If the educational agency or institution determines that there is an articulable and significant threat to the health or safety of the student or other individuals, it may disclose information from education records to any person whose knowledge of the information is necessary to protect the health or safety of the student or other individuals.”

In past instances, school districts in San Mateo County have relied on this section to issue exposure notices when students contracted contagious viruses or other ailments such as strep throat, influenza, and amebiasis.

The number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the U.S. indicates it is similarly contagious and poses a significant threat to students and staff. So why aren’t schools informing the community?

Districts provided a number of reasons. First, they claim they can contact trace and notify anyone who had been potentially exposed to COVID-19.

“We inform [the students and staff] that were in close contact during the time that the person may have been contagious. And then we interview with the person that’s positive to see who the close contacts are. And then we proceed with each individual depending on if they’re close contact or not,” Crame said. “Nobody else necessarily gets notified, other than the students in the pod and their parents. We don’t give the name of the person that tested positive.”

There are problems with this approach. As COVID-19 surges on, people have started to relax their standards and risk seeing more people. A look at many local high school students’ Instagram feeds is enough to demonstrate that people are mingling with many more members of the community than their assigned academic and athletic pods.

“A lot of kids my age have relaxed their safety measures significantly,” said Sally Olsen*, a senior at San Mateo High School. Olsen asked to have her name changed for fear of punishment from the school. “Plenty of people I know are even attending parties filled with people. I don’t think contact tracing just within pods is enough.”

The lack of social distancing and intermingling beyond the pods means that potential exposures of COVID-19 affect many more people in the community than just pod members, making contact tracing insufficient. To help slow the spread and minimize exposure in the best way possible, local districts should notify the entire community of potential exposures.

Second, the districts claim they are not disclosing information because they have incomplete data.

“I only know the number of [Carlmont] students and staff, and that number is also iffy because it’s only what is being reported to us,” Gingher said.

But why should the presence of unknown cases prevent the disclosure of known cases?

More and more students and parents are pushing to return to school as COVID-19 stretches on. However, because they are not receiving all available information about the extent of their community’s exposure, they remain dangerously under-informed about the level of risk.

“I am very concerned about returning to classes too soon. I would feel more confident knowing the number of cases in the district over time,” a SUHSD teacher said. “I also worry that the lack of clear communication could lead to some mistakes happening which could impact safety.”

*These sources preferred to be left anonymous to avoid repercussions from their schools, in accordance with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy.

**The views expressed here by Deborah Sim are personal in nature and do not represent the views of Vifor Pharma, Inc.

![One of the slides presented at the seminar shows how specific hallways will be designated as one-way or 2-way hallways. "In most cases, the one-way or one-directional hallway [is used] to minimize the crossing of students, but there are some hallways that are going to be two way," said Greg Patner, the administrative vice principal. "You can see some of those arrows are two-way arrows like near the football field, and then there's some that are one-way arrows to help students to navigate successfully around campus."](https://scotscoop.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Screenshot-2021-03-17-4.14.19-PM-900x506.png)