Life is hard enough as a high school student.

Everything seems like a competition, from trying to get the best grades to facing the pressure from universities to show your talent. However, for millions of youth, life involves watching their hometown turn to rubble as a result of political turmoil.

What if your ability to stay alive relied on moving to another country?

This is the reality for millions of people living in Yemen. The war for control of the government has taken the lives of over 2 million people, leaving behind only destruction.

Yemen is one of the poorest and most violent nations on the Arabian Peninsula, due in part to being colonized by Britain, and North and South Yemen were divided over the issue of government rule until 1990.

As the median age of the population is only 19.3 years, millions of youth have much more pressing worries than their upcoming tests. One of these teens is Matab Abdaljalil, a 17-year-old Yemeni immigrant, who grew up in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen.

Although she fled her home in 2014 during a time of government crackdown on terrorism, she often reflects on the memories of her childhood years.

“My favorite memory as a kid was playing in the streets with the boys,” Abdaljalil said. “I’m a girl but I always loved playing soccer with the boys. I made them all run after me, but they could never do anything because I am a girl.”

In 2015, a civil war broke out. The president of Yemen at the time, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, was overthrown in January by Houthi rebels apart of the Ansar Allah movement. The northern Yemeni tribe was angry with government corruption and restrictive policies on religion and so they raided the palace, forcing Hadi to resign.

The Hadi government, supported militarily by Saudi Arabia and funded by the United States, attempted to take control against the Iranian-backed rebels. This proxy-war impacted Abdaljalil’s neighborhood seemingly overnight.

“The people just left. Now you don’t find anyone there,” Abdaljalil said. “The first thing I noticed was that there was no electricity anymore.”

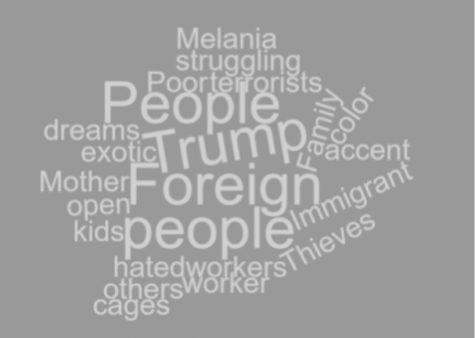

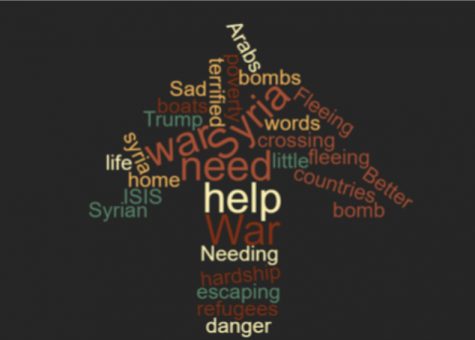

When high school students were asked what words they associated with the term “refugee,” these were the words that came to mind.

Abdaljalil was certainly not the only one facing these struggles. The Borgen Project reported that, as of 2019, over 21 million people, which makes up 80% of the country’s population, are in need of humanitarian aid.

In Yemen, malnutrition and cholera run rampant. Apart from being classified as the fifth most violent country in the world, Yemen also has the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. All of these factors have left millions of Yemenis with no choice but to relocate.

“I honestly don’t know how people still live there. People still love Yemen and they are trying to make it better,” Abdaljalil said.

Abdaljalil’s family arrived in the United States seeking asylum, but President Donald Trump’s travel ban on Yemen has stopped the arrival of immigrants.

Many Yemenis go no further than African refugee camps like Sudan’s Al Kharaz, which holds over 16,000 migrants in the middle of the sweltering desert. However, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) estimates that 100,000 to 200,000 Yemenis live in the United States as of 2019.

“I left right as the war state, but my family is still there,” Abdaljalil said. “That’s why I think I am lucky; my family sends us videos of the bombings and it’s very bad.”

Abdaljalil’s story is all too common, as only one in 10 immigrants find legal services to aid them in pursuing citizenship.

Organizations like the Arab Resource and Organizing Center (AROC) provide immigration services to Arabs and Muslims in the Bay Area. Their youth coordinator specializes in helping immigrant youth deal with hostility and language barriers.

“A lot of youth will come here having experienced a culture shock and they feel isolated,” said youth coordinator Hanan Haddad*. “After attending one of the free summer camps we provide, they are able to see that there are other people like them. That is the most rewarding part of my job.”

Additionally, teachers across the country are working to create a safe space for immigrant students in their classrooms. Among them is Ramtin Aidi, a math teacher at Carlmont.

“I want to give students the right environment to identify what makes them feel comfortable,” Aidi said.

In 2014, Abdaljalil moved to Oakland, California, which she observed to be similar to Sana’a. She reflected on how the friendly shop owners in her Oakland neighborhood were similar to the owners of markets that once lined the streets of her childhood home.

When high school students were asked what words they associated with the term “immigrant,” these were the words that came to mind

“There are a lot of Yemenis in Oakland, and there are also a lot of people who act a lot like Yemenis [culturally], which reminds me of home. The shops remind me of Sana’a, the only difference is that the streets are cleaner,” Abdaljalil said.

Although there were friendly reminders of home, Abdaljalil faced struggles assimilating into American society, most notably language barriers.

“I came here knowing two words: ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ But I had to go into high school with everyone else who spoke English as their first language. My first year here, I had very bad grades, and I was failing many of my classes,” Abdaljalil said.

But the environment wasn’t even half the struggle. Abdaljalil came across hostile people and dealt with Islamophobia in more ways than she can count.

“Of course, there are people on the streets who tell me that I shouldn’t have to wear my headscarf or that it is wrong to wear it. I haven’t had anyone try to pull it off my head yet but I have heard people call me a terrorist,” Abdaljalil said.

Aidi, who has worked as a teacher for over a decade and a half, has witnessed all types of xenophobia in schools, even though it is mostly subtle.

“Carlmont is a pretty peaceful and harmonious environment, but I would say institutional racism exists everywhere that I look,” Aidi said. “There are some things that just alienate foreigners. Teachers need to create more uniform dialogue in how they’re addressing otherness so that it’s not offensive to anybody or making anybody feel disadvantaged in any way. ”

Haddad has been seeing a more outright form of hate in recent years.

“[Racists] are ignorant,” Haddad said. “They should look back at their own family history. At one point, someone was being persecuted, someone was being looked at as the other. Unless you are indigenous or black and your ancestors came here against their will, your ancestors are immigrants.”

Judgment from inside the Muslim community has been thrown at Abdaljalil her whole life. In fact, this hostility is one of the reasons she now lives with her family in the outskirts of Seattle, Washington.

“There were many people around me who told me I was wearing the headscarf wrong,” Abdaljalil said. “Now that I am in Washington, I feel a lot safer, I feel that people accept me more.”

Haddad has seen first-hand how people will find differences between themselves before they find what unites them.

“During one of the week-long institutes we were doing, the immigrant youth would text in Arabic on the group chat and the youth who were born here would become enraged because they couldn’t read it. But, by the end of the week, they all became best friends. I think that’s because, at the end of the day, they are all youth,” Haddad said.

This unity was uplifting to Haddad, but Abdaljalil doesn’t think that the people who have shown her hostility in the past can overcome their bigotry.

“They are closed-minded. They will always think like this, they will never be open-minded,” Abdaljalil said. “But why be closed-minded, you are literally killing yourself from the inside. Everybody has a story, everybody has a hard time in their life, you just need to open your eyes and see that.”

Ultimately, it seems that the hardest part about living in the U.S. is the uncertainty of her and her family’s immigration status.

“I don’t have a green card. I’m not a citizen,” Abdaljalil said. “Because I am not an adult, I’m protected by Child Protective Services and they let my family know if we can stay at the last second [each year]. So every year, I am waiting for CPS to say, ‘You can’t live here anymore,’ and kick us out.”

Being the only one at her high school who wore a hijab, being uncertain of her ability to stay in the U.S., and being the tough little girl who would not lose a match of soccer to any boy without putting up a fight have all strengthened her determination to succeed.

“You may be mad that I am in your country but you can’t do anything about it,” Abdaljalil said. “But I can do something. I can laugh and I can smile because I am living in your country.”

*Due to the sensitive nature of the content, this name has been changed to protect the anonymity of the source.