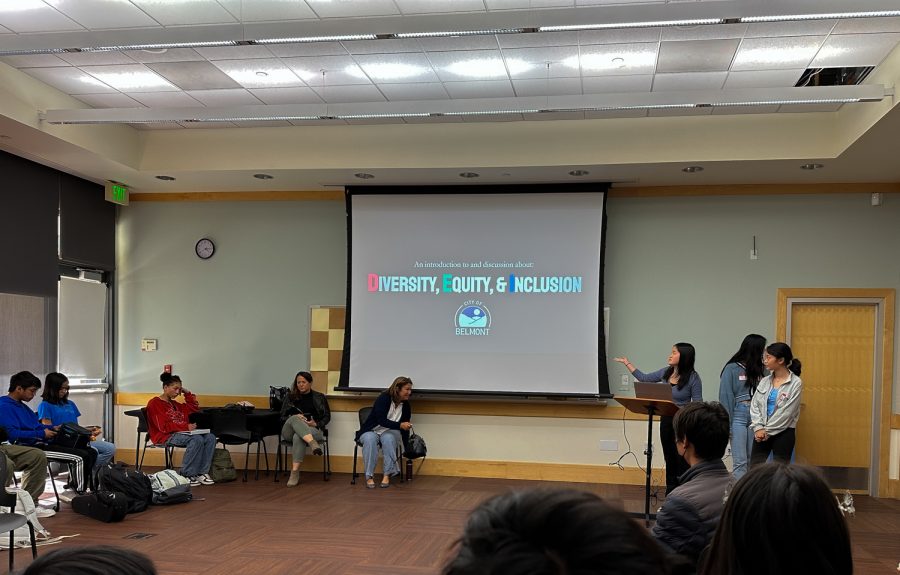

Students from Carlmont High School hosted an open discussion event about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) on May 24 at the Belmont Library to promote DEI’s importance and spark further conversations within Belmont and San Carlos.

The student organizers, Arianna Zhu, Kara Kim, Elaine Jiang, Isabella Zarzar, Sam Crowther, Tara Krishnan, and Katherine A. Zhang, partnered with Belmont’s Officer of DEI and Director of Parks & Recreation, Brigitte Shearer. Their goal with their discussion was to unite adults and children and explore personal experiences with the benefits of representation in school, work, and the community.

“When we start talking about DEI, we all must come from a place of the firm belief that every single one of us should have every opportunity available to live up to our fullest potential,” said Belmont Council Member Robin Pang-Maganaris. “Then institutions and organizations have a responsibility to use their resources to help make sure that every single person can do that.”

While the discussion event encourages DEI in the community with conversations, the Belmont City Council has been attempting a larger scale of integration, such as implementing DEI policies within the council body and in public works projects.

Belmont Mayor Julia Mates describes her ongoing DEI work as challenging but worthwhile because she can foster a culture of belonging within the community. Shearer has seen how some of Mates’ projects, like a more accessible swing set, have already begun to make Belmont a more inclusive city.

“That swing built to include disabled children gets used by everybody all the time. It’s an inclusive swing for everyone, and it honestly touched my heart and my head and helps describe what inclusion means to me,” Shearer said. “Sometimes we go to buildings, and we see the ramp that zigzags back and forth next to the straight stairway, and they’re sort of separate paths. The beauty of that swing is that it is a single path; it is a single experience for everybody.”

The student organizers of the DEI discussion event wanted to exemplify inclusive public projects like the swing that allows all people to follow the same metaphorical path and have the same access to opportunities. They also felt that more DEI discussions could bring about social change. Krisnan hopes the Belmont and San Carlos communities will get to the point where no one feels they have to fit themselves into a box to be represented.

“DEI creates a place where everyone feels not only that they’re represented, but feels like they belong,” Krishnan said. “To just be represented means that you’ve been given labels meant to satisfy a quota. To feel like you belong means that you don’t have to be hyper-fixated on parts of your identity to fit in, and you can just belong without having to conform.”

Mates describes how a large part of Belmont’s DEI work has been ensuring residents can be themselves with their unique background and intersection and still feel they belong in the community. However, not all areas view DEI in this way. Spectator and Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging at Charles Armstrong School, Annie Phun, saw the representation efforts in her home state as more harmful than beneficial due to the lack of consideration for the individual.

“I grew up in a very different location, in New Mexico, and that’s how I got to DEI work because I was very used to being isolated because of race,” Phun said. “If you have no history, then you have no self, and there’s no point of view. So a big thing for me was just learning who I am. Where do I come from, or where does my family come from?”

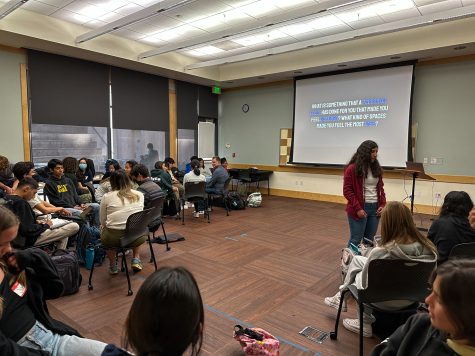

In her presentation, Shearer discussed the differences between equality, equity, and actuality. Despite having equal opportunities, everyone comes from different circumstances that can make it harder for them to access those opportunities.

“We fought for equality, but it’s not enough about equality,” Shearer said. “With equality, everybody supposedly gets the same things, but some people still can’t have those experiences, so we need equity. Everybody gets what they need because that is the goal, but there’s more. There’s reality. Some people are starting at quite a deficit.”

Those deficits can be seen in public schools especially, where students come from various backgrounds and harbor different challenges, yet often they are all pushed into the same classrooms with a single, set curriculum. Some are pressured into conforming to classroom standards.

“Whenever we talk about school, you could think that automatically all children are treated equally in schools, but in actuality, they aren’t, and the reason for that is because their teachers often are not representative of the children they teach,” Pang-Maganaris said. “It was critically important that we were always making sure that we were leveling the playing field and giving additional opportunities to marginalized children, not just treating everyone equally.”

It was significant for the organizers of the DEI event to reach middle school and high school students because they feel students are the ones who need to care about social issues for change to happen. The effectiveness of student activism can be seen in March for Our Lives and Greta Thunberg’s global climate protests.

Students make up a large community force and are the future of city councils and state legislatures. However, Krishnan wants to see an increased effort to integrate DEI into schools and hopes that events like these will get students to start thinking and talking.

“I know a lot of progress is being made toward getting more DEI involvement in schools, though a lot of that comes from the perspective of teachers and not so much from the perspective of students,” Krishnan said. “I think that students’ voices are one of the more important things that need to be heard for us to be efficient and effective in the community.”

Krishnan also acknowledged that furthering DEI discussions in schools can help teachers recognize how to support their marginalized students better and if they have unintentionally offended students with implicit bias.

Throughout the guided discussions, many teenage attendees noted their negative experiences with specific teachers and substitute teachers, where they may not have realized how their words or actions affected the student.

“Once, I was sitting behind my friend, and she was watching Netflix in class, and the substitute teacher came over and was like, ‘Hey, what are you doing? Why are you watching Netflix? Don’t you have schoolwork? My friend said, ‘Yeah, but I finished everything.’ My friend is an Asian kid, and the substitute said, ‘You should go watch some Chinese show then,’” said Ria Smilovitz, a freshman at Carlmont High School.

Krishnan believes that DEI has become a more prominent topic in schools and hopes that increased community discussion will help marginalized students feel represented. However, she also notes that schools in Belmont and San Carlos are not very culturally or ethnically diverse, making it difficult for DEI topics to be an integral part of school curriculum.

Though, It’s not just the schools. Racially, about 50% of Belmont is white, and 67% of San Carlos is white. This is due to several factors traced back to 1607, when the first British colonies were created in North America.

The discrimination that followed the slave trade, even after it was abolished, has institutionalized into modern society and has affected the housing market, the job market, secondary education, and many more aspects of society. These facets of the modern United States make it harder for people of color to integrate into white metropolises like San Carlos and Belmont.

“Unfortunately, those problems come from many things, and that’s not the type of problem that just DEI talks are going to solve,” Krishnan said. “That issue comes more from systemic discrimination, and not even this city or state government can solve that.”

However, many attendees, including Smilovitz, believe that hosting DEI discussions and prompting more talk about it within communities is valuable despite the challenges of systemic discrimination. While it will not bring immediate or even significant changes, Smilovitz believes it allows everyone to voice their thoughts, learn from each other, and later encourage more people in power to join these discussions so systemic change can start.

“Changes can come from the ripple effect, started by people who talk about it and get more people involved, so the outer circle starts to pay attention to it,” Krishnan said. “We need to start at that micro level, and it will extend beyond that to the city and state governments.”

Shearer recognizes that Belmont has become increasingly diverse in recent decades, necessitating these DEI discussions. She also realizes that businesses may see representation and diversity as another box to check off, though she believes keeping DEI a running conversation is essential.

“This is not just a fad or the end thing to do. There is data to support, for example, companies that are gender diverse are 50% more likely to outperform companies that are not gender diverse,” Shearer said. “Furthermore, ethnically diverse companies are 35% more likely to outperform. You’re getting different perspectives you may not have considered before.”

Shearer and Mates’ primary goal with the DEI discussion event and Belmont’s DEI initiatives is to promote further talks surrounding the main points of diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as about justice and action. They want residents to consider how a place or activity can be more inclusive, who is missing from the conversation, and what they can do to ensure everyone feels they belong.

“No one is an expert in this, and we’re all going to, at some point, make mistakes. We’re going to step in, and there might be micro-aggressions or even macroaggressions,” Mates said. “We’re all in this together, and we’re all going to work together, and if we make some mistakes, we’ll make them together.”