Today, a lot of teenage angst is centered around social perceptions of what they should be. Seventy years ago, there were millions of people who could not think of what they should be but instead thought of what should have been.

The Holocaust was all part of Adolf Hitler’s plan to kill all the people who were not deemed as “perfect.” He wanted to create a perfect society made up of people he called “Aryans.” However, to make an “ideal” German society, he was determined to eliminate all Jewish people, homosexuals, and any person that opposed his rule. He was determined to accomplish this goal, even if it meant killing over 6 million Jews, including 1.5 million children under the age of 8, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

In 1942, there was a 12-year-old French boy named Joseph Rotholc that would not survive this genocide, according to Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. His childhood was very similar to those who are raised now; he played, danced, had toys, and had friends, as many children today do.

Yet, in an instant, this would all be taken away.

In 1940, he was brought in to Auschwitz-Birkenau, unaware that he would never walk back through the gates. At the young age of 12, he was separated from his mom and quickly put to work. He would never play again. He would never smile again. He would never have his own life again.

When he crossed those gates, he would never feel human again.

Rotholc worked tirelessly for two years, only stopping once a day for boiled water and soup for lunch. That was the only allowed meal, and if someone were to attempt to smuggle in food and get caught, they would be executed.

Joseph Rotholc lived out his childhood like any other child in Paris, France.

His mother was sent to be executed at the killing center located in Auschwitz, which left Rotholc to live every day without knowledge of whether she lived or died.

Every day, he dealt with excruciating mental and physical pain and eventually, due to the lack of nutrition and long workdays, his bones became visible through his skin. He looked much older than he was, as the physical labor he went through had made his skin hard.

One day, it was all over.

It was on that day that he was taken for a routine shower; they made him strip his clothes and double-checked if he was hiding anything in his body. They then gathered him and his fellow prisoners into a crowded room, as if they were sheep.

Unlike the other shower rooms, this one did not have showerheads. Finally, the toxic gas Zyklon B was released into the room, causing all of its victims to convulse and choke to death. He died looking at his dad, as an insignificant speck amongst all the other victims.

Rotholc was one of the 6 million innocent Jewish lives taken.

In 1939, the first Jewish ghettos were opened. These ghettos were designed to pull the Jewish people away from society and made it so that the average citizen would not see the torture that ensued. As Hitler wanted Germany to unite, he did not want the people that lived in Germany to see their friends tortured, as it could cause possible uprisings.

Though many lives were lost, there are some that survived and live to tell their story such as Mikhail Teper.

When Teper was 16, he was sent to the Jewish ghetto outside of Odessa, formerly in the Soviet Union, but now in Ukraine.

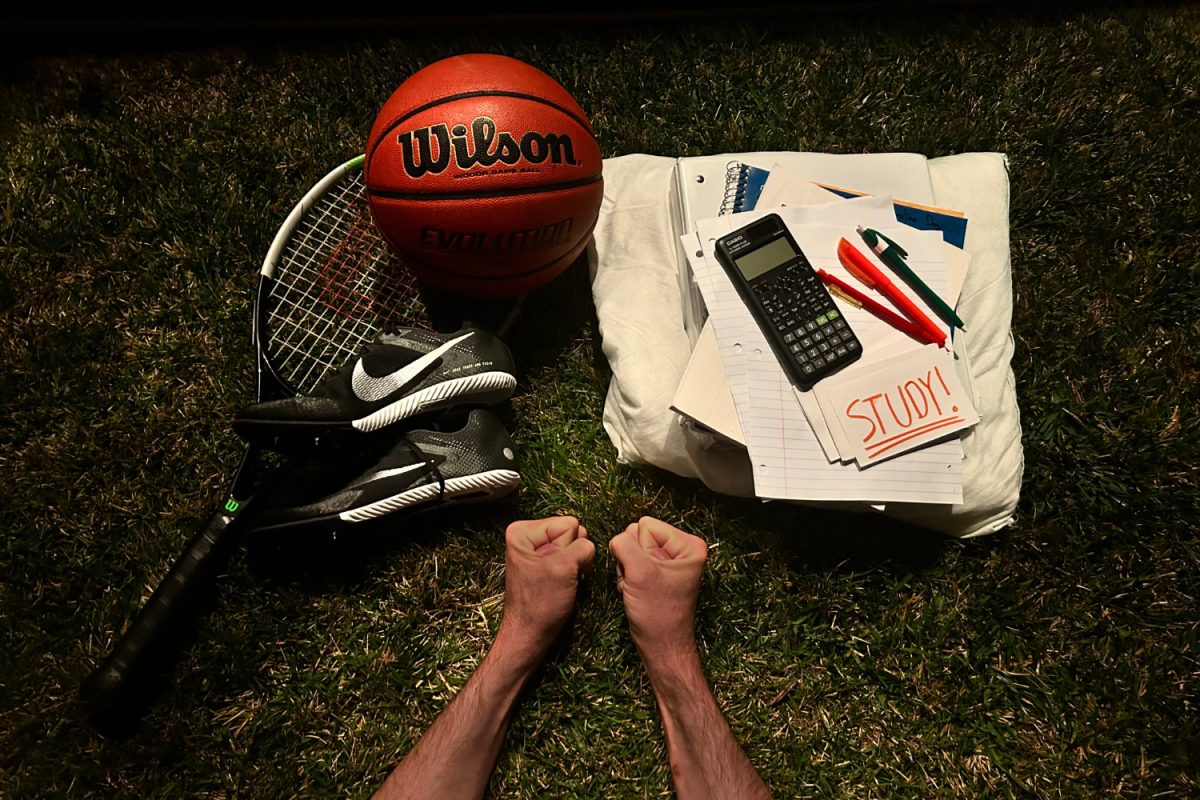

At the time, he was supposed to be a high schooler; however, instead of worrying about his next test, he worried about what he was going to eat for his next meal.

When he entered the ghetto, he was cut off from his old friends but made friends that he worked with every day. In this ghetto, he had two jobs: sawing wood at a factory and digging for an airport that would be built.

This was all he would do for three long years with minimal time to rest, if any; if he stopped for a moment, he would be punished.

As he was in the prime age for working, the amount of work he did was more than most, although they all worked the same amount of time. The most “efficient” ages in the concentration camps were those of about 13 to 20 years of age. Most over or under that age would be killed.

About a year after he stepped foot in the ghetto, he and his father were taken into a march into the nearby forest. Knowing that this could be the end, Teper and his father devised a plan. While there was a distraction, he and his father would sprint into the cover of the forest.

When the distraction came, they did just that.

“When we were led to the mass grave where we were supposed to be shot and killed, my dad and I ran away and barely escaped. Later we were caught and beat up badly. My dad was in a lake all night; the water was to his neck, as the Nazis were looking for them, and he needed to hide,” Teper said.

When Teper was caught, the guards did not spare his emotions; they beat him until he could not move.

“We would get beaten by these long wooden sticks if we didn’t do what we were supposed to do. They did not care who you were or what your age was, and they weren’t afraid to beat you or even kill you,” Teper said. “Sometimes they would do it for sport.”

Up until Teper’s liberation from the ghetto, his father smuggled food into the ghetto and risked his life just to see his son.

After the Jews were liberated by the Soviets and British, Teper was thrilled but forever changed from the treatment he endured.

“I was as happy as humanly possible when I was liberated. Before we were released, we were beaten and bruised. Afterward, I had emotional and physical scarring that I still live with it to this day,” Teper said.

Mikhail Teper sits with his medals after WWII around 1945.

After they were liberated, Teper and his father were drafted to the front lines of the war, where he would fight for two years to defeat the Nazis. Teper was wounded three times during this painstaking process, but he did not give up, as he remembered what the Nazis had done to him and to his fellow people.

Teper is currently alive and well at the age of 95.

Before the Holocaust, Hitler needed a scapegoat to blame Germany’s economic recession. The people that he ended up blaming it on were the Jewish people.

They were a convenient scapegoat because, since the 1700s, banking was their main profession, as it was one of the few professions they were allowed to pursue. Likewise, disdain for the Jewish people grew due to the wealth they accumulated from this profession, making it easier for Hitler to rally people against them.

Before 1948, the last time the Jewish people were all together was 2000 years prior, preceding the Diaspora. This whole time they were yearning to finally be together, to have a homeland. However, as anti-Semitism grew, this did not seem like a possibility.

But in 1917, their hope grew.

The British government announced the Balfour Declaration, which promised a home for the Jewish people. When the Holocaust hit, this hope did not cease to exist.

The soon-to-be national anthem of Hatikvah broke out amongst the people. The motive that kept them working was that there would be a homeland if they just survived until the next day.

This is what is different among the Jewish people.

According to PBS, one of the reasons they have survived this long is not because of their numbers, but instead because of their hope and resilience. This is why, in the springtime of 1948, the hope outgrew the doubt, and after being dispersed for 2000 years, they got their home.

Throughout history, there have been many genocides, the largest being the Holocaust. Many people of different ethnicities, colors, ages, and sexual preferences all have been persecuted and the reason why this occurs is because people turn a blind eye to the facts.

As of December 2019, many genocides still occur, and yet no one cares. The Uighur Muslims are being kept in detainment camps, the Darfur genocide of Sudan is still progressing, and recently, 1,000 protesters were killed in Iran. Anti-semitism has risen 150%, but no one seems to care.

In the age of social media and widespread “awareness,” people seem to be the least aware of conflicts in plain sight. In this age of enlightenment, people seem to be the least enlightened ever.

The solution to all of these conflicts may not exist; however, anyone can make a difference. Instead of searching for the most recent celebrity couples, people can educate themselves on these ever-growing struggles, so that the horrors of the Holocaust and genocides past and present don’t continue to persist.