On their way to school, a student steps into their building’s elevator to find a woman clutching her purse as she sees them. After arriving on the ground floor, the woman rushes to the exit. The student walks out, disoriented with the woman’s tense reaction, yet continues the journey to school.

Once they arrive and sit down for class, they find that their peers and teacher alike are surprised they received an “A” on the most recent exam. However, this surprise does not stem from the student’s intellectual capabilities.

Instead, each of these reactions is tied to an uncontrollable yet restricting factor: their skin color.

Instances like these may not seem overtly racist but are continuously experienced by students of color nationwide. In many cases, the woman who clutched her purse or the peers and teacher that wrongly assumed are not aware of their discriminatory behaviors. Despite this, centuries of systemic racism lie just beneath the surface of such actions that propel an inherently racist society.

Underlying biases often create environments in which people of color may not feel welcome. The American school system, especially, demonstrates the implications behind these unconscious reactions.

“In middle school, a substitute teacher called me out as the ‘Black girl’ in the middle of class. ‘That Black girl over there in the back,’ she said. Being called out like that was very uncomfortable for me, but she just seemed okay with it. After that, nothing happened even after I brought it up to a teacher,” Carlmont junior, Jordan English, said.

On a broader note, the microaggressions that Jordan experienced reflect the system’s flaws at an institutionalized level. In a Cambridge University study, the “Social Science Research on Race,” authors Calvin Rashaud Zimmermann and Grace Kao measured racial divisions within teachers’ evaluations of students. Ultimately, they found that teachers rated Black students far lower academically, even when testing identically to their white peers.

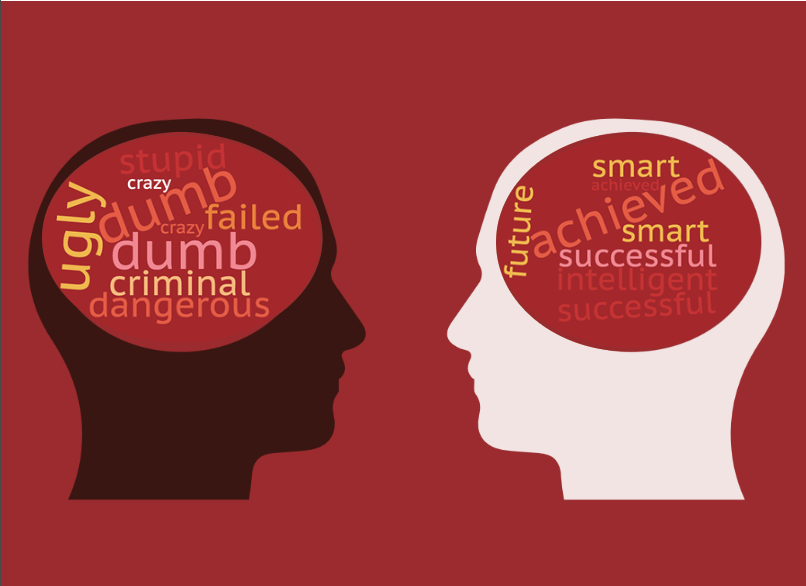

These biases are primarily accepted as effects of institutionalized racism, thus creating a society that subjects individuals to a particular form of thinking. Ultimately, this impacts peoples’ actions and perpetuates stereotypes that thrive within American classrooms.

Such stereotypes have the power to create hostile environments for people of color, where teachers’ expectations of student achievement may be far lower for non-white students.

“If Black students are taught by educators who do not believe in their full potential, these subtle biases can accumulate over time to create a substandard educational environment that fails to prepare at-risk students to become fully contributing members of society,” stated a 2013 Ohio State University study on implicit bias.

Racism is thus not only defined by the treatment of others, but also by institutionalized ways in which discrimination hinders opportunities for minorities to succeed. According to the U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection, Black students are nearly four times more likely to be suspended and nearly twice as likely to be expelled as white students from kindergarten through high school.

The continuing pattern of educational disparities further demonstrates the relevance of racial inequality in the modern school system. For instance, a 2019 study by the California Department of Education found that 33% of Black students scored proficient in reading levels compared to 65% of their white peers.

The school-to-prison pipeline also exemplifies the gap in student achievement. This concept represents the unequal placement of disadvantaged minors into the criminal justice system. Often this is due to the reliance of underfunded schools on harsh punishment practices. Ultimately, the link between the two represents a clear intersection of the issues within both policing and education practices.

“If you look at systemic racism, look at the fact that a large segment of the population, particularly African American males, are ending up in prison. It’s going to prevent them from practicing law,” Director of the Caribbean Law Programs, Jane Cross, said.

Implicit biases that reflect disparities in the education system can be traced through the history of racism implemented throughout America’s legal policies. Centuries of social divisions and racial categorization work to establish this bias, ultimately shaping how people view others. Because of this, stereotypes are often linked to systemic policies that serve to justify these inequitable practices.

Because of their frequent subtlety, implicit biases that indicate such policies seem permissible, as many continue to overlook them. Nonetheless, implicit bias continuously impacts people of color, and many have had to experience this form of racism at a vulnerable age.

“As an African American woman that grew up in Texas, I had the typical stories that focused on always being suspect of being up to no good or having to prove myself beyond the expectation of others. I experienced being called abhorrent names by both peers and adults due to the color of my skin,” Belmont City Councilwoman, Davina Hurt, said.

As English explains, this behavior is deeply rooted in a society designed to allow oppression.

“These little day-to-day things add on to making it seem like that’s just the way the world is, which then contributes to systemic racism. This allows people to grow up in environments where they believe those actions can be tolerated in the rest of the world. With that, it’s an ongoing cycle and a big part of where systemic racism comes from, as it’s tolerated so much in our schools and other systems,” English said.

However, since people frequently form and act upon implicit biases without individual awareness, they become difficult to measure. Unlike explicit racism, implicit biases are automatic reactions that function as microaggressions, attitudes, or emotional responses towards certain groups.

Regardless, there are readily-accessible opportunities to become aware of how these biases function while measuring their prevalence on the average individual. The Implicit Associations Test (IAT) exemplifies such a chance to trace attitudes and conceptual stereotypes towards marginalized groups.

According to Cross, education marks the first step towards mending stereotypes and racism rooted throughout America’s school system. Implicit bias training, for instance, intends to make people more aware of how their actions regularly contribute to discriminatory practices.

“It’s good for discussion not just to take things at face value, but also to consider other implications there might be. They might be seemingly innocuous, but they can also have deeper implications based on systemic racism embedded in our systems. Unless we recognize it, we can’t deal with it, and we can’t seek to minimize it,” Cross said.

This push for self-awareness brings into question the importance of educating students about systemic issues and Black history. According to a 2017 study by LaGarrett J. King, “The Status of Black History in U.S. Schools and Society,” mandated Black history in several states like New York and Florida demonstrate the importance of understanding the long-term effects of implicit biases.

Additionally, many students seek change beyond the community to push the fight against implicit behaviors and the policies that exhibit them.

“I think the one thing everyone can do is educate themselves, or attempt to educate themselves further because you can’t do anything if you don’t truly know what’s going on,” English said. “But at the same time, being aware of something isn’t enough. You have to be actively trying to change what’s going on. Making people educated is important and all, but it’s also important to make sure that you’re helping them understand what they can do to better the situation.”

As Hurt reflects, resolving the impact of biases against people of color and other minorities will not happen in a day. Nonetheless, everyone has the opportunity to make a conscious effort in becoming more aware of how their behaviors reveal issues ingrained within the American education system.

Ultimately, she explains that fighting against the root of these persistent issues may profoundly affect the modern normalization of racial injustices.

“I’m hopeful for tomorrow because of the large number of allies who have stepped up for equity and justice. While we have not eradicated racism, I am inspired by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s quote: ‘Fight for the things that you care about but do it in a way that will lead others to join you,’” Hurt said.

Jerylin Fry • Nov 12, 2020 at 10:59 am

Thank you for writing such an informative article. It helped me learn new information that I was missing! thank you again!!!