Everyone has been there: walking into the pantry, reaching for your favorite bag of chips, only to realize it’s past the date printed on the package.

Contrary to popular belief, expiration dates may not draw a hard line between edible and inedible. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), apart from infant formula, these dates are not required by federal law and do not indicate product safety, but instead its assumed freshness by the manufacturer.

After the date passes, perishable foods may deteriorate in quality or change in taste, however, they remain safe for eating. It is up to the consumers themselves to determine whether a product shows signs of spoilage.

“Fruit and vegetables don’t come with dates, so I judge by looking at them, but food that has dates, or comes in labeled containers, like jars, I determine visually and by smell,” said Carlmont parent Tak Frazita. “If something looks off, I don’t consume it, but if it looks fine, then I do.”

Selena Mao is a research manager at ReFED, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing food loss and waste through data. She shares Frazita’s viewpoint, emphasizing that consumers should rely on their own judgment rather than strictly adhering to expiration dates.

“It’s important to remember that food doesn’t really come with a stopwatch,” Mao said. “Oftentimes, the best barometer for assessing whether or not food is good is trusting your senses. Trust your gut instincts — if it smells bad, if it looks bad, and if it feels weird — not just a stamp on the package.”

USDA also estimates that 30% of the food supply — or 80 million tons according to ReFED — is lost at the consumer and retail levels. One source of the loss is outlined as customers throwing away wholesome food due to misconceptions about the detailing of labeled dates.

“On the grocery store shelves today, there are more than 50 differently phrased date labels on packaged food,” Mao said. “Some phrases are used to communicate the peak freshness of a product, or when a product is no longer safe to eat. Others, like ‘Sell-By,’ are only used to inform stock rotation, but the downstream impact of that is it leads a lot of consumers into thinking that that product is no longer safe to eat.”

Legislation is working to correct this, with Gov. Gavin Newsom signing Assembly Bill (AB) 660 last year. The bill requires standardized dating language, including “Best if Used By” to state quality in comparison to “Use-By” as an indicator of actual food safety. It will take effect on July 1, 2026.

“Our hope is that AB 660 will provide the blueprint for more federal-level action. It’s really remarkable: Newsom’s signature of really a first-in-the-nation bill we think will start to end consumer confusion on expiration dates that so many of us have experienced,” Mao said.

Other countries, such as France, have also joined the effort. The first country to do so, their 2016 law bans grocery stores from throwing away excess food approaching their dates, prompting them to donate to food banks and charities.

Still, grocery stores often take the brunt of the waste effect due to their responsibility as the first seller after the distributor.

“There are two separate categories that unsold food goes into,” said Ian Moore, a supervisor at Lunardi’s Market. “Some items, for the most part, dry goods, we send back to the distributor, and we’ll get credit for whenever we have to order again. Other products, depending on where they’re coming from, we just have to throw out. That’s usually perishables, like yogurt, milk, and other similar goods.”

Frazita reflects on this, finding himself especially keen on the viability of products while in stores.

“When I’m shopping, I probably pay more attention to expiration dates than the food that’s at home. If food is close to the date, I avoid it. If it’s past, it’s definitely not a question that I don’t purchase it. I pay especially close attention to milk and eggs,” Frazita said.

Thus, grocery stores have begun to adopt different practices, from launching sales to rotating stock, to avoid falling behind on supply.

“When we have overstock, we’ll usually put it on sale. For instance, chips will be, and then people will have more incentive to buy them, so we’ll run through that stock that way,” Moore said. “We always try to stay on top of things. We try to rotate our stock so whatever’s gonna go bad soon, we try to keep towards the front so people grab it first.”

Methods like these allow stores to keep supply levels under control, avoiding the dreaded food waste problem.

“I’ve seen grocery stores that suffer from food waste, and it’s horrible seeing how much they toss into bins and what’s not being distributed,” said Christian Santana, a closing manager at Mollie Stone’s Markets. “I just wish there were more food banks and more people we could distribute products to that are soon to expire.”

Meanwhile, salvage grocery stores, which offer food products traditional grocery stores cannot sell — due to past expirations, dents and tears, overstocking, or imperfect items — for extreme discounts, also help narrow the waste gap.

“Overall, salvage grocery stores are like turnarounds for perfectly good food that we generally toss; they make it cheaper for consumers, and, obviously, better for the planet,” Mao said. “They play a pretty big role in ensuring food goes to their intended outlet of feeding people.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports food waste as the single most common item to be found in landfills or incinerated in the United States.

According to the U.N., it makes up an annual 8% to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, nearly five times those generated from aviation.

“When food is sent to landfills, it doesn’t just sit there; it decomposes and emits methane,” Mao said.

Methane is one of the most powerful greenhouse gases. It is 86 times more potent in warming than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period and can remain in the atmosphere for 12 years, thus drastically increasing the severity and rate of the climate crisis.

Not only this, but wasted food also becomes a product of wasted work, creating a combined $1 trillion toll on the global economy every year, according to the U.N.

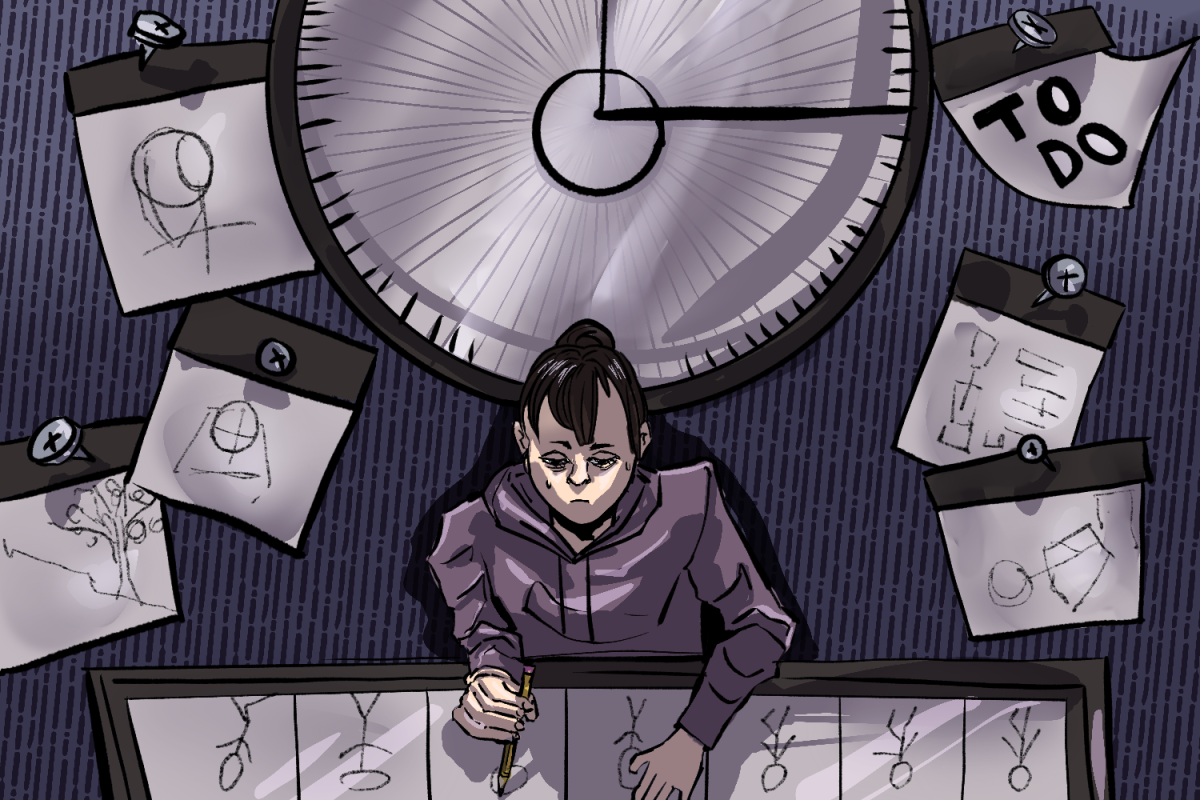

“Wasting food means wasting all the resources — the water, the energy, the labor — that went into producing it. On an economic scale, we as consumers lose billions of dollars annually by bringing away food prematurely,” Mao said. “What we throw away alone, due to our inability to adequately perceive what date labels mean, leads to throwing away roughly $30.5 billion worth of perfectly good food a year.”

However, Mao still finds hope for a more sustainable future in the growing awareness and change in consumer behavior.

“Food waste isn’t inevitable — it’s a problem that we created, and it’s one that we can solve,” Mao said. “Luckily, it is an issue that I think falls at the heartstrings of most people because of our ubiquitous connection to food — everyone touches food, everyone knows just how much effort goes into food.”