Race doesn’t define you, they say.

Yet in a society so rooted in racial classification, stereotypes and prejudice are mundane experiences. Race has integrated its way into countless aspects of life, from daily interactions to shaping identity.

“We don’t even think about it. It’s like fish swimming in water. They don’t know they are breathing water because it’s part of everyday life,” said Professor LeiLani Nishime, who specializes in multiracial and interracial studies at the University of Washington.

Everyone develops a sense of racial identity as they grow up. Schools teach them awareness from a young age. They begin to recognize faces around them and in media that resemble their own. They start to place others into socially constructed boxes, simultaneously seeking ones for themselves to fit in.

Racially ambiguous people, however, exist beyond many boxes acknowledged by society. They demonstrate how intricate the topic of racial identity can be, and remind the world that not everyone falls under explicit labels.

What is racial ambiguity?

The term “racially ambiguous” describes anyone whose racial background is not easily identifiable based on their outer appearance. Despite all transcending the boxes of racial distinction, they can hardly be categorized as one group of people.

Some are of mixed descent, with diverse ethnic backgrounds. They often don’t resemble any distinctive group, and their racial makeup can be difficult to track.

“I identify as mixed. An oversimplification of that would be to say my dad is Black, and my mom is Brazilian, but going back a few generations, I have other races in my extended family,” said Dylan Crockwell, a junior at Carlmont. “Explaining my identity can be a little confusing, and many people don’t even believe me until they realize I don’t fit into any other categories.”

Racial ambiguity can also refer to monoracial people who are misidentified due to their appearance. They typically contradict the physical attributes associated with their racial group or have features resembling ones commonly seen in a different race.

The racially ambiguous experience

Depending on their appearance and the environment they live in, racial ambiguity can mean something different to each individual. There is no universal experience, though they collectively occupy a unique space in society.

Because people rarely correctly identify him, Crockwell doesn’t fall under many racial stereotypes, allowing him a certain sense of freedom compared to those whose race is more easily distinguishable.

“For most of my life, race wasn’t really something I thought about,” Crockwell said. “Since people don’t have any stereotypes of me, and I’m not easily categorizable, I haven’t experienced any racism. I know members of my family who have, though.”

Much of that, Crockwell admits, has to do with his community. California is the most diverse state in the U.S., according to the World Population Review. With diversity comes exposure to different cultures and more inclusivity.

“As someone who spent part of my life in the South, I completely believe that the Bay Area is a large exception to much of what you see across the country,” Crockwell said. “Living here not only makes it possible to leave the box of racial identity that many people are pressured into but also enables you to choose the culture and people you surround yourself with.”

Crockwell only became curious about his racial identity after people started bringing it up in school and social life. After running a Google search in eighth grade, he promptly came to the conclusion that he was fully Pacific Islander.

“So I told my Black dad I was 100% Pacific Islander and he laughed at me. That’s when I started to try and figure out what my racial makeup actually was,” Crockwell said. “I didn’t even know my dad was Black until I had to ask him because I noticed he and other members of his family had darker skin.”

Since then, Crockwell has grown closer to his ethnic roots. Though race was never a major factor in his life, learning about the experiences of his parents and grandparents exposed him to the world of racial categorization.

“[My dad] has also been called racial slurs in New York and harassed for his race. He tells me that he wasn’t accepted by the white kids and they called him slurs, and he wasn’t accepted by the Black kids because his skin wasn’t dark enough and they called him a ‘half-breed,’” Crockwell said.

Becoming familiar with his racial background and the stories he heard from his family has allowed Crockwell to form his perspective of race and develop his own identity.

“Listening to their worldviews inspired me to speak out against social injustices and empowered me to know more about myself,” Crockwell said.

While it liberated Crockwell from many constraints his monoracial-presenting relatives experienced, ambiguity can also mean being a target of stereotypes and discrimination.

Carlyn Weinstein, a high-schooler living in Virginia, identifies as white. However, people often mistake her for being Wasian (white and Asian) or Hispanic. Questions about her racial identity typically come from a place of genuine curiosity, but some interactions are also marked by bigotry and ignorance.

“I’ve had a lot of people be very kind to me when asking about my race and ethnicity, but I’ve also had ones that come up to me assuming things and being really racist,” Weinstein said.

Her peers are often the perpetrators of these insensitive remarks.

“At school, I get called slurs mostly relating to Asians,” Weinstein said. “It doesn’t hurt my feelings, but it irks me that my peers think it’s okay to say such things.”

Ambiguity places Weinstein in an awkward space. She faces judgment because of her Asian-presenting features, yet many also find it problematic when they realize she is of a different race than they expected.

“People tell me I’m trying too hard to be Asian just because I look it and I’m interested in things that come from Asian culture and countries,” Weinstein said. “I also get told that I’m Asian-fishing after I say that I’m white, which makes it feel like I’m doing something wrong when in reality I’m not.”

Despite the social pressure to fit in with one racial category or the other, Weinstein has learned to disregard unsolicited comments.

“I was insecure for a while, but now it doesn’t really affect me. It’s just something I’ve kind of learned to deal with since there’s nothing I can really do about it,” Weinstein said.

Re-evaluating racial categorization

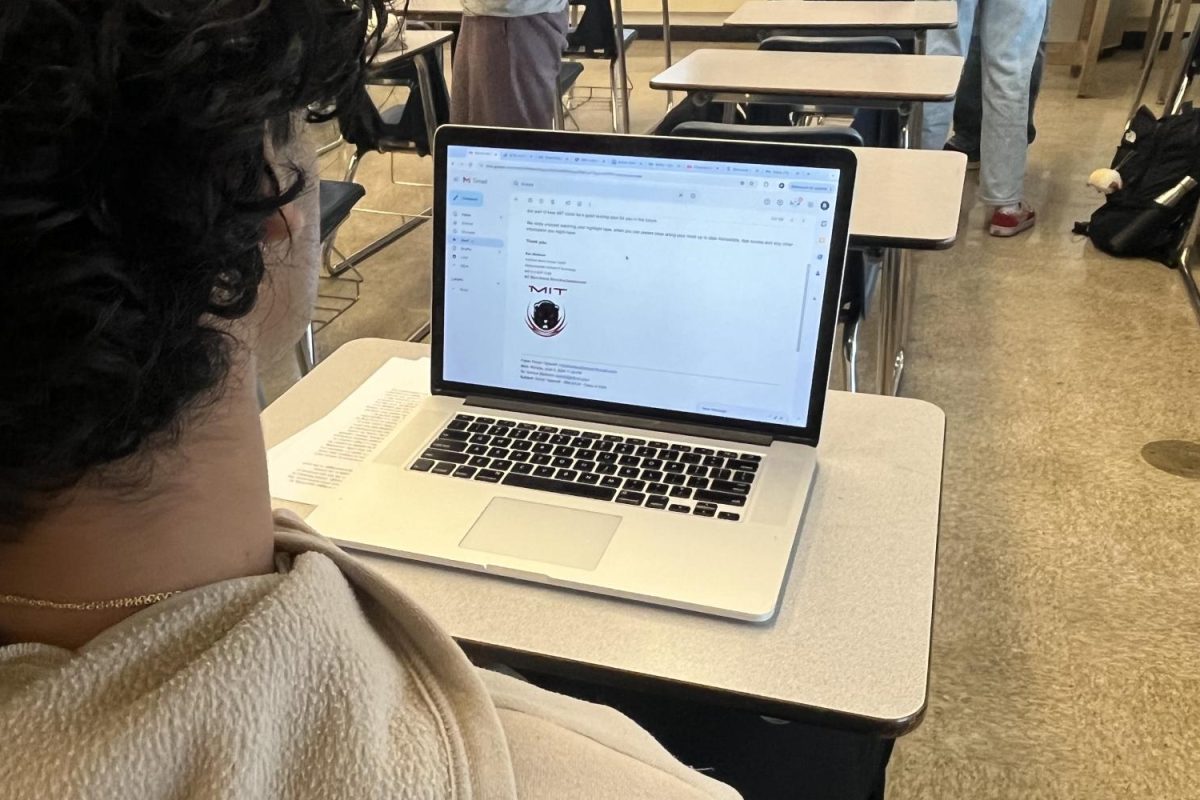

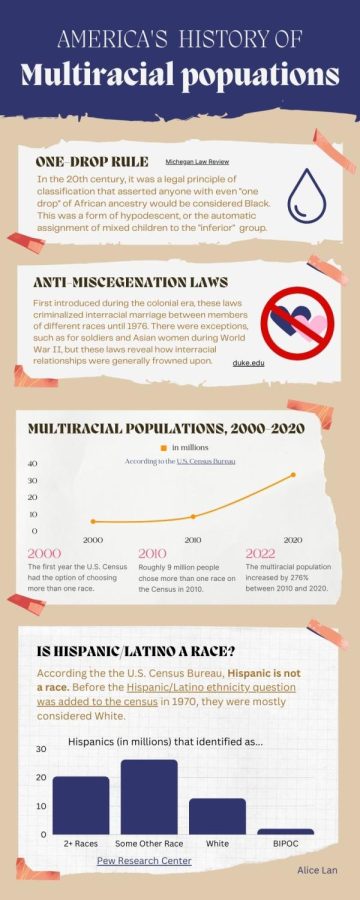

Though they have always existed, multiracial populations were largely excluded from the topic of race in the past. Their presence, however, has become increasingly prominent in recent decades, challenging the racial categories perpetuated by society.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the percentage of people who reported multiple races increased from 2.9% in 2010 to 10.2% in 2020. As more and more people are falling under the umbrella of racial ambiguity, it becomes difficult to categorize people by physical appearance alone.

“Broader society should have a better grasp of our racial history and be less fixated on particular racialized features to determine someone’s racial identity,” Nishime said. “We should be asking ourselves why we have such a limited visual vocabulary when it comes to race.”

Racial identity is often tied to physical appearances, but understanding the history behind such classifications offers insight into the dilemma that multiracial populations pose to society’s definition of race.

“I think our ideas about mixed-race people and who we count as mixed-race follow from our racial politics. The idea that the mixed-race population will expand depends on who counts as mixed-race,” Nishime said.

The U.S. Census Bureau often revises its definition of race due to shifting demographics, reflecting the dynamic nature of race as a social concept. For example, the “Latino/Hispanic” ethnicity question did not appear on the census until 1970, and the “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” categories were grouped together until 1997.

Mixed-race people have always existed, but up until recently, they were placed under a single racial category. Only starting in 2000 did people have the option of identifying as more than one race.

Since then, the U.S. census has recorded exponential growth in multiracial populations, signifying that more and more Americans are choosing to step beyond the constraints of a single-race identity.

Aside from federal classifications, race in modern society exists as a means for people to separate from or relate with each other.

“My dad used to tell me about how other Black people tended to be comfortable with each other without knowing one another because there was an immediate sense of belonging, shared experiences, and similar culture,” Crockwell said.

Racially ambiguous people are often unable to strike these instant bonds. They remind society that while many racial communities share a group identity, self-identity goes beyond physical appearance and cultural roots.

“I think it’s important to be careful when trying to identify yourself and find a strict ‘box’ to put yourself into,” Crockwell said. “Race shouldn’t define a person, but it should be talked about and explored.”