Scorpions litter the floor. The heat is unbearable, blazing down on your bare skin, causing you to burn up everywhere. You live in a makeshift tent the size of a small bedroom. Its inside consists of a mere handful of blankets. That is the bed you’ve been given.

Hundreds are dying around you each day because of the horrible conditions. You come from a cold climate. Your body is not accustomed to the dire conditions. You have been forced out of your home, and many of your family members have been killed. You are having to call exile camps your home for the time being. You are given a very small amount of money every month to survive, but it is not even enough to buy food for one meal a day.

For most of us, this seems like the stuff of nightmares. For Kashmiri Pandits, it was reality.

However, the story of Kashmiri Pandits (Pandits are Hindus; they are a caste of Hindus) has only begun to emerge in the past few weeks, in light of the recent release of “The Kashmir Files,” a movie depicting the effects of terrorism on Kashmiri Pandits from 1989 to 1990. For the past 30 years, the story of Kashmir has remained unknown to most of the world.

“It’s very important for people to learn about Kashmir; it’s an integral part of India, and […] people should know what happened with Kashmiri Hindus there,” said Dr. Arti Bhat, a Kashmiri Hindu whose family had to leave Kashmir when she was a teenager.

Kashmir is a region in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, and it lies between India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Its geographic location is the reason for much of its history because a part of it is administered by India and another part by Pakistan.

Pakistan is a Muslim-majority country, whereas Kashmir had a Hindu-majority when it was first created. As the years have passed, the population of Muslims in Kashmir has increased greatly, but Kashmir remains home to Hindus as well.

Some Pakistanis and Kashmiri Muslims have believed that Kashmir should be annexed to Pakistan due to its now Muslim majority. However, Kashmiri Hindus have disagreed, believing that they are not bound to Pakistan and should be able to practice their own religion.

Because of this, though the situation is much better today, Kashmir has faced a lot of unrest throughout its existence. There have always been conflicts between the different religious groups, but the most deadly wave of these conflicts occurred from 1989 to 1990, the same years “The Kashmir Files” is set in.

“[What happened in Kashmir] is not a problem for Kashmiri Pandits only,” Ravi Tikkoo, a Kashmiri Hindu who had to leave Kashmir between 1989 and 1990 and seek refuge in another part of India, said. “It was a unique kind of intolerance [and] systematic ethnic cleansing. [Things like what happened in Kashmir] keep on cropping up in different parts of our world, so everyone needs to know and understand such patterns of ethnic or religious cleansing by any particular community.”

In July of 1988, revolts in Kashmir, against the Indian government, sparked an uprising amongst Kashmiri terrorists following commands from terrorists in Pakistan. Misusing Islam to justify their actions, over the course of the following few months, they killed between 30 to 80 Kashmiri Pandits and kidnapped and tortured Kashmiri women. (The exact number of deaths remains disputed today because a lot of information was concealed during the time of the killings; some news sources say that over 300 Kashmiri Hindus were killed.)

Their ultimate goal was to usurp Kashmir for Pakistan, and Kashmiri Hindus were given the option to either “convert, leave, or die.” Some sources claim that around 10,000 Kashmiri Hindus converted to Islam during this time.

The terrorists also killed those who supported the Indian government or did not support the terrorists’ actions but killed Kashmiri Pandits solely because of their religion. The Indian government’s lack of action during this time also played a large role in aiding the terrorists.

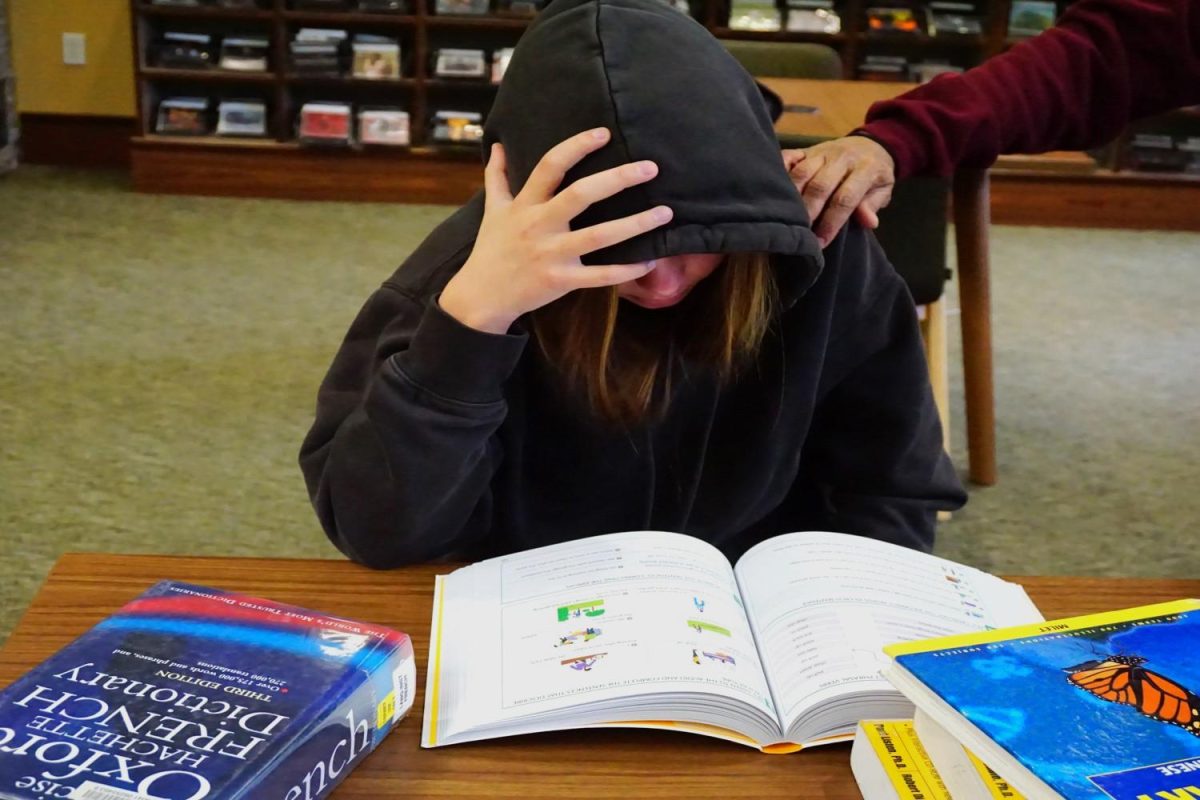

“I was 16 years old when [I had to leave Kashmir],” said Jyoti Ganjoo, a Kashmiri Hindu who had to leave Kashmir between 1989 and 1990. “The night that I had to leave my birthplace along with my parents is a night that changed my persona overnight. [What happened in Kashmir] took my youth years away […] Overnight, the shift for me was from thinking of glam, fun, fashion, beauty, and dresses, to survival, safety, and security.”

Ganjoo says she was at the top of her grade in her high school in Kashmir and had achieved a state rank in academia. She had always aspired to be a cardiologist. However, when she and her family had to leave Kashmir, she had to leave that piece of her behind as well. When they settled in Delhi, her accomplishments in Kashmir lost their meaning. She was no longer at the top of her grade, which meant she could no longer study cardiology. She now works as an engineer.

“Kashmiris who have been subjected to [what happened in Kashmir] have lost a phase of their lives, which is irreparable,” Ganjoo said. “When my friends say they are going to their hometown during vacation, the thought that I don’t have a hometown left to go to, pinches. So, in hindsight, it also means that [Kashmiris] have been wandering since then, with no place to call our own.”

Despite its prevalence in the modern-day, especially in South Asia, Kashmir is a subject that most people do not know about. Many believe this is because Western media tends to not cover many conflicts outside of the West, such as conflicts in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and more. Spreading information and telling the story of a place that does not normally get any coverage, is the purpose behind the creation of “The Kashmir Files”: to educate those around the world about the importance and history of Kashmir.

“Stories [like that of Kashmir] are important,” said Isabelle Cloy, an American citizen studying to become a journalist. “These are humanitarian stories just like other stories that CNN and ABC and [other news organizations] cover, but these stories are excluded and it sucks.”

![Kashmiris (primarily Hindus) protest the Indian government for not taking appropriate action regarding the conflicts in Kashmir. "Personally, [what happened in Kashmir] was one of the worst tragedies of my life," Ravi Tikkoo, a Kashmiri Hindu who had to leave Kashmir between 1989 and 1990 and seek refuge in another part of India, said. "[My family] had to leave everything behind, without thinking, just to save our life."](https://scotscoop.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/crowd-gfceef49a8_1920-900x600.jpg)