When smoke rolls across the sky and fires consume another forest, Californians accept it as inevitable.

However, the truth is that with each fire, firefighters must contain them. Some of these heroes come from unlikely places. They are prisoners.

Some brave inmates defend California by taking on the most essential and fearless duties. They become firefighters.

1600 prisoners are working in fire camps as of May 2021. About 900 of these are fire line qualified. They are all pivotal players in the fight against fire.

“Inmate firefighters have played an important role in fighting wildland fires for many years and are hands down some of the hardest working individuals on the fire line,” said Jim Loscutova, the Fire Chief at Pleasant Valley State Prison.

An inmate’s day begins at fire camps as they embark on another project. Fire agencies receive custody of them, and they assist in a job. Not all tasks are related to fire, but inmates are always helping the community.

The work an inmate performs is essential but difficult. Working against a fire requires certain equipment and techniques that inmates practice while helping the community. It requires a lot of physical labor and can be strenuous.

“The physical labor that I did in fire camp, I have never worked so hard in my life,” said Michelle Garcia, the program director for Anti Recidivism Coalition and former inmate firefighter.

As these inmates assist in various assignments, they are always on call to help put out fires. Many times the hand crew’s primary duty is to start cutting line. Cutting line is a fire fighting tactic that involves clearing brush and vegetation to create a line without fuel. This process stops a fire from spreading further.

Bulldozers or other equipment also cut line to create a break in the forest. However, bulldozers can’t go everywhere. There are many different resources used to fight fires that all work in tandem. Ground crews are just one piece of the puzzle, but they are crucial in the firefighting process.

“The engine companies start laying hoses on the ground, the hand crews and the bulldozers start cutting lines, and the air tankers and the helicopters drop water and retardant,” said Justin Schmollinger, deputy chief with CalFire. “It’s a coordinated event with all of our resources fighting the fire.”

Sometimes ground crews must hunker down and fight the same fire for multiple days. In that case, they work on and off shifts, constantly fighting a fire until it is put out.

Inmates must put a lot of dedication and hard work into fighting fires, but everything they give comes back. When on projects, inmates get extra money hourly, plus an additional dollar when on fire duty.

However, pay is hardly a factor. While working in fire camps, inmates have the opportunity to reduce their sentence under Proposition 57. In general, every day of work earns two days off an inmate’s sentence.

There is also a sense of freedom when in a fire camp. It feels less like a jail. Inmates can work outside and give back to their community. They get downtime, and in general, the rules are less strict.

In comparison, prison life can be strenuous. The atmosphere of jail puts a lot of pressure on its inhabitants. Fire camps can act as a safe haven for inmates.

“It’s a softer way to do your prison sentence. Although it’s harder labor, the demands of prison lead to a hard life,” Garcia said. “[In jail] you’re locked up, you have nothing, but in fire camp, the privileges are just a little bit better.”

Another upside is the skills inmates learn. These experiences can help inmates return to the community. Convicts in fire camps have held jobs as firefighters and completed a lot of manual labor. The work ethic learned at fire camps can also help inmates get jobs in the fire service.

Another upside is the skills inmates learn. These experiences can help inmates return to the community. Convicts in fire camps have held jobs as firefighters and completed a lot of manual labor. The work ethic learned at fire camps can also help inmates get jobs in the fire service.

“We do hire a lot of these individuals as well once they parole,” Schmollinger said. “I can’t tell you how many people we’ve hired to CalFire that have been promoted up the ranks, all the way to Chief Officer.”

Becoming an incarcerated firefighter can help inmates rebuild even if they don’t choose careers in a fire. It sets up a foundation for the healing process people must go through as they leave jail.

After coming home, many will find it hard to rebuild their lives. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, as many 83% of inmates will return to jail at some point. In addition, being incarcerated leaves a stain on a person’s record and can prevent them from finding jobs. In addition, many inmates have not received proper training or schooling to succeed in a career they would enjoy.

After a long disconnect and biases in the employment process, it is difficult for former inmates to rebuild their lives. Many find themselves falling down a hole, unable to reintegrate.

“I really struggled when I first came home, to the point that I didn’t necessarily want to kill myself, but I didn’t know how to live life,” Garcia said. “I didn’t want to be the old person, but I didn’t really know who the new person was.”

However, it is possible to reintegrate. Doing meaningful work can help former convicts forgive themselves. It shows that they were able to do something positive while being incarcerated.

Becoming a firefighter at a fire camp is one of these examples of meaningful work. It can help plant the seeds to the journey of recovery after coming back home. Fire camp gives prisoners a purpose while in jail.

“Who doesn’t think of firefighters as heroes?” Garcia said. “You actually have the same work ethic as them, and now you are working just like a hero, and you start to forgive yourself. There is some healing that takes place.”

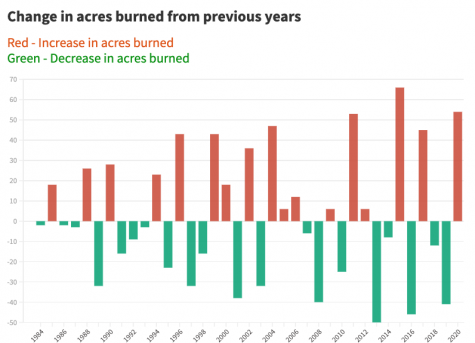

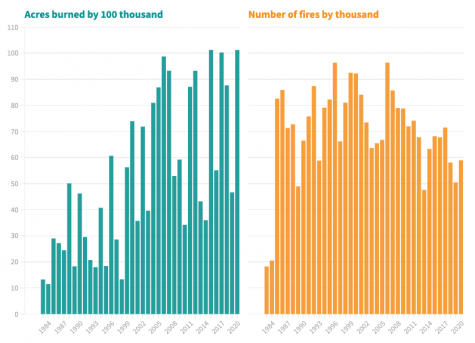

Inmates can gain a lot by becoming firefighters, but they have their work cut out for them. Fires have grown increasingly dangerous, heightening the need for firefighters. In 2020, fires destroyed over 10 million acres across the United States.

“Global climate change is a thing and something that we’re definitely experiencing on the fireline,” said Zachary Ellinger, the wildfire mitigation and education specialist for the Bureau of Land Management. “We’re seeing fires get bigger, faster, and generally harder to control.”

For California, 2020 was a record-setting year. 4.2 million acres burned the biggest fire season in years. The August complex fire was the largest fire of 2020. It consumed over 1 million acres, by far the biggest in California history.

The 2021 fire season has been damaging as well. The most extensive fire of this year is the Dixie Fire, which is over five times as large as Singapore. In addition, the Caldor fire has grown into a dangerous blaze and caused Carlmont to cancel sports practices earlier this year due to the smoke.

“What we’re experiencing on the West Coast right now is a resetting fire regime; nothing ever gets to be bigger than grass or brush,” Ellinger said. “That’s kind of a pessimistic view; I’m hoping that we don’t get to that point where there are no more trees, but if we don’t change our ways, pretty soon, that may be the outcome.”

A significant cause for concern is that future years have the potential to be even worse. However, there are many ways to stop fires. Most of the effort must come from people being willing to step up and keep California safe. In addition, fire agencies are implementing new strategies to keep fires at bay.

“We’re having to proactively combat that problem by doing things like cutting trees down and doing prescribed fire,” Ellinger said.

As fires have been escalating, inmate firefighters have also been in low supply. This is somewhat based on an early release policy to combat COVID-19. As jails were filling up, prisons tried to cut down capacity to maintain social distancing and prevent spreading sickness. To do so, they released many “lower-level” prisoners early.

Many inmate firefighters are lower-level inmates, so they were the first to be released. In general, COVID-19 hindered the amount of readily available inmate fire crews.

“It’s hard because we don’t have enough crews to put out the fires,” Schmollinger said. “I should have 2,584 inmate firefighters, but I currently have 894.”

Although the fire season has been getting worse, it can be tough for formerly incarcerated people to join the fight against fire. Many fire agencies say they will hire previous inmates but do not hire people without EMTs. Until recently, former convicts could not get an EMT license. This dilemma is why many firefighters choose to work for CalFire as they do not require an EMT license.

CA’s inmate firefighter program is decades-old and has long needed reform.

Inmates who have stood on the frontlines, battling historic fires should not be denied the right to later become a professional firefighter.

Today, I signed #AB2147 that will fix that. pic.twitter.com/15GJ7Gijt7

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) September 11, 2020

However, last year AB2147 was signed. This bill would allow those who worked in fire camps to expunge their record. One of the effects of this bill is that former inmates can now get EMT licensing.

“For many years, inmate firefighters have been able to apply with CalFire and US Forestry with a felony on their record, but could not apply with any county or city municipality,” Loscutova said, “This bill opens many doors for careers in the fire service.”

This bill does not apply to all inmate firefighters. It allows former inmates to remove only the crime that brought them to jail when they went to fire camp. Previous jail sentences do not get erased.

In addition, AB2147 only covers those in fire camps. Firehouses do not qualify under AB2147. They are fire stations within a jail that focus mainly on prison issues instead of wildfires.

“I feel that people in the firehouse almost deserve that [to qualify for AB2147] more,” Garcia said. “They have literally cleaned up the blood from fights and dead bodies, broken or missing limbs. It’s graphic and horrendous what they do, and they don’t qualify [for AB2147]. It just really baffles my mind.”

A lot of hard work that plays into putting out fires is often overlooked. Countless hours go into protecting the lives of Californians.

Incarcerated people are rarely considered heroes. Nevertheless, all Californians owe our gratitude to inmates.

“In this work, humanization is important,” Garcia said. “Once they [general population] see the real-life stories, it becomes easier to accept change.”