Greetings, traveler.

Gather round, one and all: disembark your spacecraft, bring your weary steed to our stables, hang up your dirty cloak on a peg. Draw your chair close to the fire, and prepare yourselves for a tale.

Welcome to the first installment of “The Lord of the Reads:” a deep dive into the world of fantasy and sci-fi literature.

As a second-semester senior, I’ve seen most of what the public education system has to offer when it comes to assigned reading. Though I love English class, I’ve noticed a conspicuous absence of my favorite kinds of literature: the kinds of books with magical powers, space travel, and dragons. The books I’ve read for school have been incredibly valuable to my education, but I’ve noticed that fantasy and science fiction have been sorely neglected in the classroom, almost as if they don’t belong in an academic setting. I want to flip this narrative. Authors like J.R.R. Tolkien, Brandon Sanderson, or N.K. Jemison may be vastly different from Shakespeare or Austen, but that does not lessen their literary, cultural, and educational value. Their books have a place on our shelves right next to Macbeth or Jane Eyre.

In order to prove that fantasy and science fiction have real academic value, I have dedicated myself to the pursuit of writing about my favorite books for an entire semester. I plan on five total installments of this project, including analysis, reviews, and general fun. Each time, I will seek to answer the question: do these books deserve a place in the classroom?

We’re beginning with the father of modern fantasy himself, and the author of some of my favorite books. British author John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (or Jolkien Rolkien Rolkien Tolkien, as young fans like to call him) needs no introduction. His works such as “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” are staples upon bookshelves across the globe, and have been adapted into movies, video games, and an upcoming TV series from Amazon. I’ve been a fan since I first read “The Hobbit” as an 8-year-old. This article is part love letter to (and part criticism of) the books that have shaped not just a genre, but a generation.

Before we start, a quick disclaimer: I am not a Tolkien scholar, and my knowledge of his life and work is limited. Readers each have their own interpretations of the books, based on their own experiences. All of these opinions are my own, and may change over time. I am just a little fellow in a wide world, after all.

Why Middle-Earth?

At this point, everyone in Carlmont Journalism is all too aware of my love for Tolkien’s literature. My (professional) Twitter page is clogged with “Lord of the Rings” memes, and our adviser and I have derailed several meetings about publication schedules with in-depth conversations about hobbits and dragons. My reasons for loving these books would probably rival “The Silmarillion” in length and detail, but there are a few key reasons they are some of my favorites.

Each time I return to the books, there is something new and exciting to discover. There is always a new way to look at them that I hadn’t noticed before: the anti-industrialist story of forests rising up to swallow factories, or the ways in which Tolkien’s experience in World War I influenced his storytelling. I could probably revisit the books hundreds of times and not get bored.

Tolkien’s gorgeous (though often dense) prose demonstrates some of the most masterful use of language I’ve encountered. His writing is laced with both subtle humor and intense emotion, effortlessly shifting from joyful to witty to somber and back. His worldbuilding conjures up breathtaking views of crumbling ruins, sweeping plains, and perilous mountain ranges.

The superbly written characters are also a reason that I and thousands of other readers continue to return to Middle-Earth. One of the defining characteristics of Tolkien’s writing is the idea of “the little guy.” The true heroes of Middle-Earth are not warriors, kings, or wizards, but small, seemingly insignificant hobbits. Tolkien could have gone the obvious route and made his larger-than-life characters like Aragorn and Gandalf the main focus of his storytelling. Instead he chooses to focus on unlikely (and usually unwilling) heroes like Bilbo, Frodo, and Sam, making them the true heart of Middle-Earth. These characters and their unexpected courage are relatable enough that every reader can see themselves among a world of supernatural powers and ancient magic.

Though men far outnumber women in Tolkien’s tales, his female characters are some of his strongest. When I first read “The Lord of the Rings” in middle school, women like Eowyn, Galadriel, and Arwen stood out to me amidst a seemingly endless sea of male characters. While I personally wouldn’t characterize Tolkien as a feminist by any stretch of the word, he has created some of the most empowering and complex female characters that I’ve ever read.

Take Eowyn, daughter of kings, shieldmaiden of Rohan. Her story is one of the best pieces of character development that I’ve ever read. Over the course of “The Lord of the Rings,” she transforms from a young woman trapped by society into a war hero and finally into an older, wiser healer. She proves that she can stand up to the forces of evil with a sword in her hand, but also rejects the brutality and grief of war, saying, “I will be a shieldmaiden no longer, nor vie with the great Riders, nor take joy only in the songs of slaying. I will be a healer, and love all things that grow.”

Eowyn is not the only heroic woman in Tolkien. There is also Luthien, who single-handedly brought the Dark Lord Morgoth to his knees and stole a Silmaril from his crown. Galadriel, one of the most powerful elves in Middle-Earth, helped to drive Sauron from his fortress of Dol Guldur and was eventually responsible for its destruction. Haleth, a character in Tolkien’s legendarium, was described as “a woman of great heart and strength” who rose to become her people’s greatest leader.

The women of Tolkien, though they are few and far between, are not tokens for men to fight for or plot devices to move the action along. They are each deeply developed, powerful characters in their own right, and one of the best parts of the books.

It’s easy to praise Tolkien’s genius, but it’s also critical to recognize and understand the less rosy aspects of his life and work.

Racism and Antisemitism in Middle-Earth

It is impossible to read Tolkien’s work without recognizing some serious flaws, including the racial bias and antisemitism present in his storytelling. His cast of characters are overwhelmingly white, a pattern that is continued in Peter Jackson’s film adaptations. The only explicitly non-white characters are the Haradrim, a race of men who were compared to trolls. Tolkien’s depictions of orcs are also problematic: in one of his letters, he describes them as “squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.”

In addition to his disturbing characterization of the Haradrim and the orcs, Tolkien’s inspiration for the dwarves is based on problematic stereotypes. The author remarked in an interview that “the dwarves, of course, are quite obviously, couldn’t you say that in many ways they remind you of the Jews? Their words are Semitic obviously, constructed to be Semitic.” Dwarves in Tolkien lore are often portrayed as greedy or overly concerned with gold, which is a connection to centuries-old stereotypes of Jewish people and money. They are also depicted as having prominent noses and long beards, which is another antisemitic trope.

Tolkien’s deliberate use of racist and antisemitic stereotypes in his tales have implications beyond just Middle-Earth: as one of the earliest authors of modern fantasy, his work (and his biases) have inevitably influenced the entire genre.

Scholars have written extensively on the subject of race and antisemitism in Tolkien’s literature, and each one comes to different conclusions on the topic. Was Tolkien simply “a product of his time”? Do his ideals of unity, friendship, and peace outweigh his troubling biases? Is his creation fundamentally racist? Almost 70 years after the publication of “The Lord of the Rings,” these questions still trouble scholars and fans. I don’t have an easy answer to any of them, but I do know that they can’t be ignored. In order to truly understand Tolkien’s work, we have to come to terms with the ugly side of it as well as the wonderful. If we try to justify this ugliness or sweep it under the rug, we allow it to continue permeating the genre it helped to shape.

Wrapping up: Do these books deserve a place in the classroom?

The truth is that Tolkien’s work already has a place in the world of academia. From feminist and queer theory to postcolonial criticism and critical race theory, there are any number of academic lenses that have been applied to Middle-Earth. Tolkien’s mastery of prose, storytelling, and worldbuilding is something both college professors and 17-year-old AP Lit students can learn from and admire. Scholars have been writing, studying, and often arguing about everything “Tolkien” for decades now.

“The Lord of the Rings” is not an easy read by any means. I’ve reread the trilogy multiple times, and I still have no idea what’s going on sometimes. I’ve seen his writing described as “beowulfian,” and that’s not inaccurate. Tolkien’s work is so dense, in fact, that entire college courses are dedicated to studying it. To top it all off, “The Lord of the Rings” even has its own Sparknotes page.

It’s already been settled that these books are a cornerstone of English literature. The real question here is whether Tolkien, who wrote his books almost 90 years ago, is still relevant to today’s readers. I may be biased, but I believe this question deserves an emphatic “yes.”

In fact, the tales of Middle-Earth have become even more relevant to my life lately with their stories of strength, courage, and hope in the face of overwhelming adversity. I know it’s a cheap move to bring up quarantine in a seemingly unrelated article, but the past year or so has been rough: I and many of my friends have experienced most of our senior year from behind our laptop screens, unable to interact with each other the way we used to. College application season has come and gone with its annual stress and burnout, and we are facing our last semester of high school with slim-to-none chances of a prom, graduation, or any real semblance of normalcy. Add to that fears of COVID-19 and a rocky political transition, and things can seem pretty bleak.

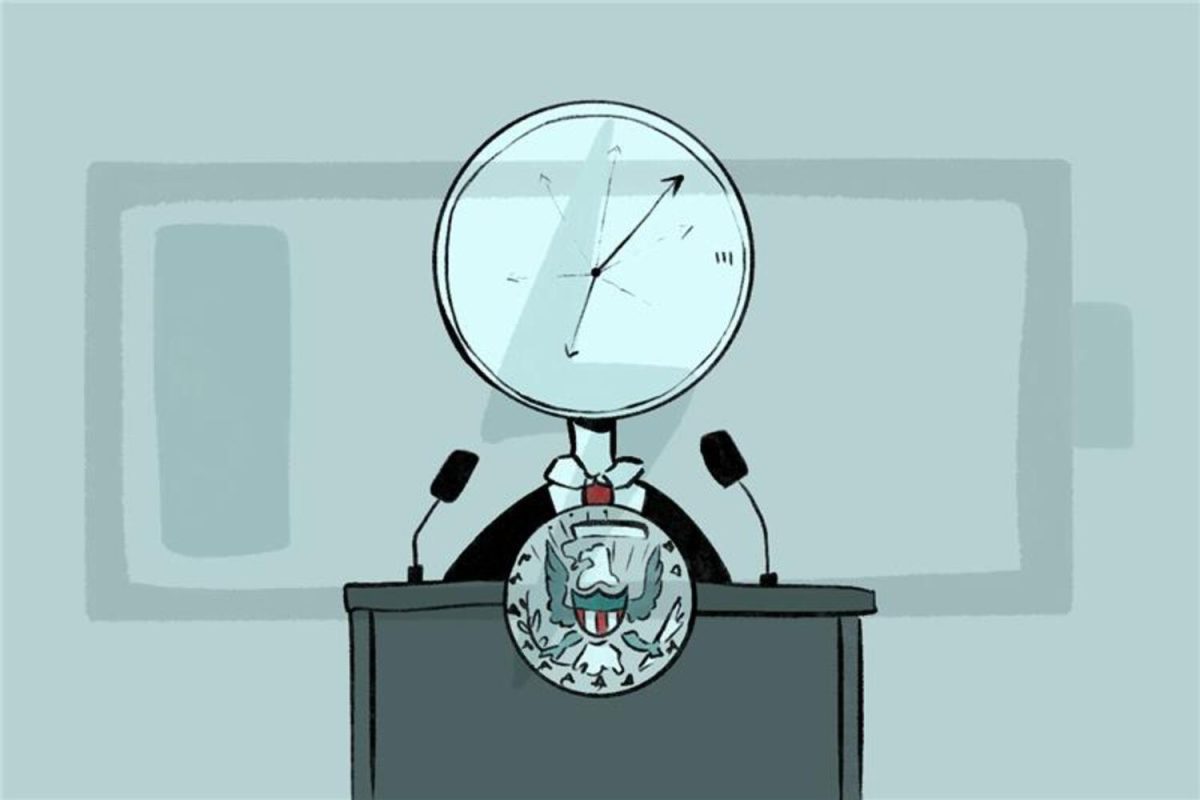

Often, I find myself wishing that none of this had ever happened. Of course, that’s when Gandalf’s words pop up in my head: “So do all who live to see such times, but that is not for them to decide. All we have to do is decide what to do with the time that is given us.”

4368,187337″ align=”center” background=”on” border=”none” shadow=”on”]