Constantina Bakolista left her job as an academic researcher at UC Berkeley earlier this fall to work with those in her lab to lobby against workplace power abuses in the University of California (UC) system. In the following winter, along with Bakolista and her colleagues, 48,000 teaching assistants and academic researchers went on a month-long strike across 10 UC campuses.

Unified under their demand for livable wages, their efforts reached new heights in early December, strategically coinciding with the universities’ finals weeks.

“These strikes were actually planned for some time and have been coordinated with all the different units in postdocs and academic researchers. We thought we would have more power if we would be striking all together,” Bakolista said.

The demand for higher pay, especially at universities such as UC Berkeley, and UCLA, where the cost of living is very high, was largely a response to the universities’ housing crises. The growing number of students on campus has heightened these crises.

While the number of admitted students has been on the rise in recent years, the number of professors at each university has remained constant. Instead, what increases is the number of administrators, including teaching assistants (TAs) and scientific researchers, resulting in what Bakolista refers to as a “bloated administrative body.”

“People severely underestimate how much work the TAs do. All the professors do is show up two or three times a week to lecture for a few hours. Everything else in the class is handled by the TAs,” said Arin Gadre, a sophomore at UC Santa Cruz.

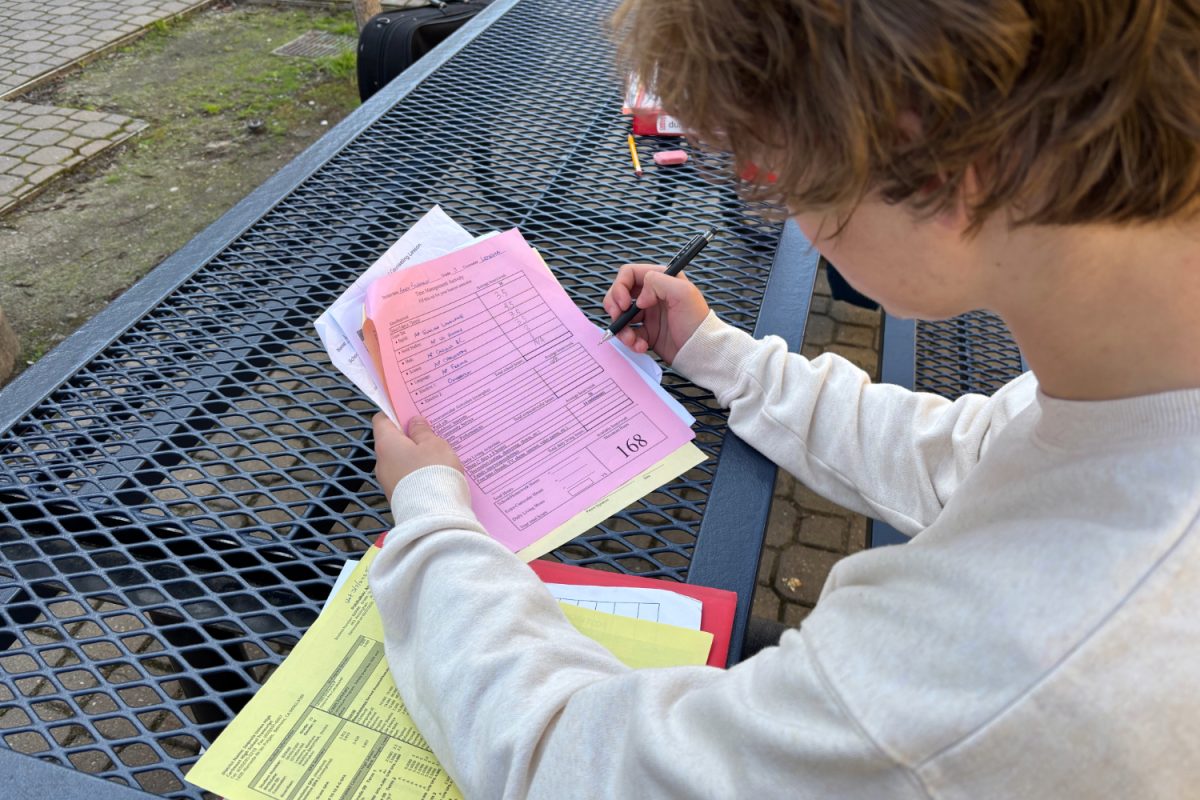

The UC schools expect their TAs to grade assignments, teach discussion classes, give out quizzes and tests, teach lab sections, and handle other student concerns.

The striker’s vitalness to the function of the universities was felt by students during their finals weeks when the TAs intended disruptions impacted the way each campus handled their finals.

“A good number of professors chose to hold finals online. One of the biggest impacts of the strike was on the discussion sections, where the TAs often review lecture material, give out quizzes and practice material, and most discussion sections were canceled after the strike started,” Gadre said.

Along with the strike’s influence on finals, TAs and academic researchers caused further interruptions by stopping gas and UPS deliveries at the picket line. Additionally, bus systems such as the Santa Cruz Metro Bus System refused to enter the campus in support of the strikes, impacting student transportation.

“The stikes definitely delayed grades and even canceled some final projects or essays since the people who were supposed to be grading them weren’t there. If they weren’t canceled, other teachers just gave everyone a 100% on their finals or made them optional,” said Lucia Acosta, a freshman at UC Santa Barbara.

Due to such grading setbacks, UC Berkeley tried to sidestep the need for graduate student instructors.

“The professors were being asked to do all the grading, which is the labor of the students on strike, and told them they would be paid extra. When there is an issue like this, the universities are not supposed to rely on their academics but are expected to go through the unions,” Bakolista said.

The UC’s Librarians and non-Senate Faculty, in a cease and desist letter to the university, accused UC Berkeley of taking up struck labor, an illegal labor practice, for their attempt to bypass the TAs.

“The UCs have been formally saying on their websites that they’ve been bargaining in a fair manner with the students and unions, but this is just one example in which that was not happening,” Bakolista said.

At the heart of the issue, the strikers had been negotiating for assistance with the rent burden which would be compensated by a higher salary. With the UC system being the largest landowner in California, owning over 756,000 acres of land, many postgraduate students are arguing for their rents to be reduced.

“Many of these TAs have to commute almost two hours a day to get to campus or even hold multiple jobs to overcome debt,” Bakolista said. “The universities should put more money in paying the people who actually do the teaching and the grading, and it does have the funds to do that.”

In mid-December, as the negotiators of the universities and unions failed to meet on common ground, a third-party mediator, Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, had to step in. By reviewing the universities ‘ various data reports, Steinberg determined whether the UCs had the funds to meet the striker’s demands.

As of Dec 16, the strikers have been given a tentative deal that promises to significantly increase the pay of about 36,000 unionized teaching assistants and researchers. Under the agreement, those with an annual salary that started at $23,000 would see their salary grow more than 55% in the following two years.

“While this is an improvement on the schools’ previous offer, which was made pre-mediation, it still falls short of graduate student demands,” Bakolista said.

Graduate students and TAs continue to debate the offer, for which its final voting will take place on Dec 23.

“There is significant momentum behind a no to the deal. Even so, I hope these results show young people the inherent power that comes with organizing,” Bakolista said. “There’s been a recent resurgence of unions that confirms that there are effective ways to bring about better living conditions and a more equitable society.”