Some come for a better education, some because of their parents, while others come seeking financial security.

The California Department of Education recorded that there were over 2 million students recognized as English learners (EL) enrolled in California schools in 2018. Out of those, 802,293 were high school students, 373 learning at Carlmont.

Hanqi Wang is one of them. Wang plays the piano and dreams of pursuing a degree in natural sciences. He is a sophomore and came to the U.S. from Saint Petersburg, Russia, for a better education.

Wang said, “My mother thinks education here is better than in Russia, and she wanted to give me the best learning opportunities out there, and that’s why I’m here.”

However, the journey came at a cost, as Wang’s English speaking skills have yet to improve and, as of now, he is struggling to communicate with native English speakers.

“I studied English in Russia, but that is not enough to understand everything,” Wang said. “The language barrier is still an obstacle because I often don’t understand what people say and just smile.”

Another international student at Carlmont is Kseniia Naumova, a freshman, long-time dancer, and a cheerleader. Like Wang, she came from Saint Petersburg; however, her reason for immigrating was her mother’s occupation.

Naumova has had to undergo many challenges when it comes to school. Besides the language barrier, adjusting to American schools has been harder than she thought.

“When I first came here [America], it was really hard to speak and understand people,” Naumova said.

Despite the challenge, Naumova has overcome the language barrier and adjusted to the school environment nicely.

“I didn’t know English, but then it got easier after six months,” Naumova said.

Meanwhile, students like Camila Fonseca, a sophomore, come to the U.S. because their families seek financial security, as Brazil is currently facing a financial crisis.

Eitan Urkowitz at the Peterson Institute for International Economics wrote, “Brazil is engulfed in another political scandal that has sparked investor panic and has thrown markets into disarray.”

The director for Latin American Studies at the same institute, Monica Debolle, elaborated on the point in the same publication saying that the “scandal is … a continuation of the corruption scandal that has been plaguing Brazil for nearly three years now. But this time, it’s even bigger than we thought.”

The real-time data of Brazil’s CME delayed price shows a dramatic decline starting Jan 22, 2018.

When Fonseca lived there, her family had a lot of stress over paying bills and taxes.

“My dad and my mom decided to come here because of work. Working in the U.S. is better than it is in Brazil. They thought life here would be better for us, me, and my brother,” Fonseca said.

Since transferring to Carlmont, she has enjoyed the opportunities that American education offers.

“I like it more here because I get to learn more and also study English,” Fonseca said. “[Studying at Carlmont] is so different for me because I don’t speak English. But I think it’s okay because I try my best every day.”

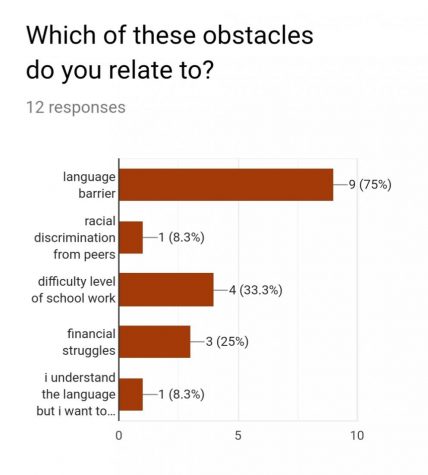

The most common obstacle for immigrant students is language. A survey conducted shows the challenges Carlmont ELA students consider to be the most apparent in their lives. The bar graph based on the data collected shows that 75% of them consider the language barrier the most challenging obstacle.

A short survey of EL students conducted at Carlmont.

Melody Liu, a senior at Carlmont, shared her experience with adjusting to life in America during her middle school years.

“I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t know how to speak English. Everything was hard, and I was so isolated. When I first started school, every day I needed to translate word from word … and it took me a long time to do middle school level work,” Liu said.

Luckily, there is an English Language Acquisition (ELA) program that helps students like Wang, Naumova, Fonseca, and Liu not only to obtain an adequate level of English but also to understand and fit into American schools.

The English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC) is a test that students take when they first transfer to a new school from a different country. It determines who needs to be a part of the program and for how long.

“The state of California has a language exam for all the students whose first language is something other than English. When they enter a school, they take that exam,” said Jenny Lord, one of the ELA teachers at Carlmont. “For some students, it places them for ELA level of support, and some students can be newly arrived, but they’ll be out in their grade-level English class.”

Lord is a Bilingual Research Teacher (BRT) who has been working at Carlmont for 10 years; nine of those years have been dedicated to helping international students feel welcomed and understood. Likewise, she speaks three languages — Portuguese, Spanish, and English — so she can better connect to her students and their parents.

“Being a resource teacher for me is connecting students with services like how to navigate Carlmont … it’s just being that first person for the student that they interact with, that helps them connect,” Lord said.

Most of the international students have to take the ELA class in the first few years of their arrival; however, there are exceptions.

Students like Sarga Nair, a junior at Carlmont, who come from countries with English as their second national language, usually have a good enough understanding of English to take the mainstream classes. Nonetheless, that does not mean that they know and understand as much English as the local students do.

Nair, in particular, came to the U.S. from India.

“The only difficulty I had was English, I suppose, because in sixth grade we did Greek and Latin root words, and I wasn’t aware of such things when I was in India because there we were learning other things like grammar and that kind of stuff,” Nair said.

On top of overcoming the language barrier, some students have to deal with racial discrimination and misconceptions.

“I think there’s just this lingering fact … this perception that you are less civilized which is the kind of image that the old America used to give. That’s not how it is anymore, but with the racist encounters that I’ve had, there have been times where I didn’t understand why people are treating me a certain way,” Nair said. “I want people to know that not all Indians are the same. We’re all very different — different colors, different skin textures, different languages, different cultures — but we’re still us.”

Nair isn’t the only student who feels this way.

Liu said, “I always hear people say that Asians should be good at math … and whenever I’m in a row to check [my work], they ask me why I’m there, and I don’t understand why they think it’s necessary to ask such questions.”

Even though racial discrimination is not the biggest problem that international students face, it is still important.

“There are so many similarities over all the years of [international] students of just wanting to be successful, wanting to have friends, wanting to have fun and to learn,” Lord said. “Students are students.”