As her fingers run through the racks of rejected shirts and long sleeves, she wonders if what she is doing is right. It’s hard to ignore the accusations that she’s benefitting herself by stealing from the poor.

However, these accusations shouldn’t carry much weight.

A common misconception about thrifting is that when people in the middle-class shop at thrift stores, the prices increase and items are no longer affordable, which can be harmful to those who thrift out of necessity.

In reality, people are doing more good than harm by shopping sustainably.

Although a valid issue, gentrification is not as problematic in thrifting as it is said to be.

“I think if you’re shopping at a local business, that’s helping out,” Maria Valle-Remond, a frequent thrifter and advocate for sustainable shopping, said. “But if you go out of your way to a low-income neighborhood and shop there, constantly, that’s slowly gentrifying the place.”

Though some argue the rise of thrifting is detrimental to people struggling economically, there are a host of benefits it creates.

For one, it creates a more welcoming environment for people who are thrifting out of necessity. Valle-Remond noted as a kid, thrifting’s image was embarrassing and caused her to stop. In recent years, the perception of thrifting shifted positively, and she fell back in love.

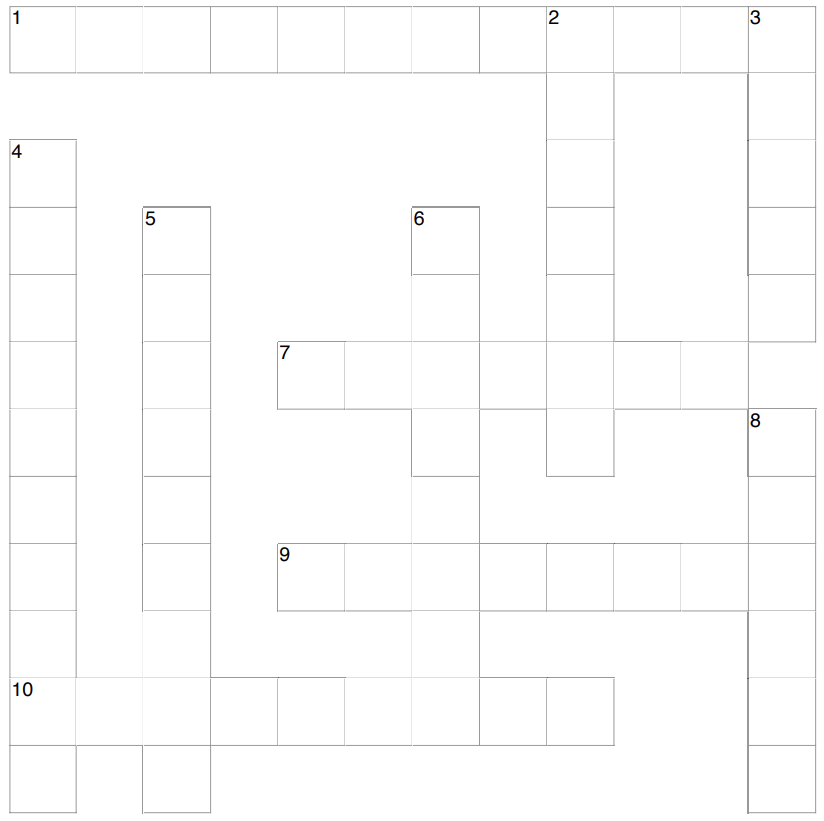

thrift tips by Marrisa Chow

The normalization prevents a more significant number of children from feeling ashamed over their shopping locations. These changes also encourage parents to support thrift shops, a more sustainable option due to children’s rapid growth. Additionally, it gives more people cause to donate their clothes rather than throw them away.

But while the normalization of thrifting is good, thrifting becomes more controversial when people buy and resell items.

As the secondhand shopping movement rises, so do secondhand digital retailers. Apps like Depop have amassed 21 million users on its global marketplace. But many people seem to have a bone to pick with Depop sellers, specifically those who hunt down bargain deals and relist marked-up prices to gain profit.

“I feel like it is kind of irresponsible to go to thrift stores just to sell. You should at least wear it,” Valle-Remond said. “I know people who go out with bags of clothes, just to sell them to make an individual profit, and that doesn’t seem like the best to me.”

Critics accuse Depop sellers of greed and dishonorable intentions. They claim that this buy-then-resell business model seems to be one of the drivers in gentrification and depletes the clothing supply.

However valid this concern may seem in theory, it’s not well-founded in actuality. Thrift stores continue to receive donations regularly despite second-hand sellers buying items. ThredUp, an online thrift and consignment store, has seen a 50% increase in donations just over the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many sellers have noticed that thrift stores always seem to be full of clothes, and the items they buy and resell don’t make much of an impact on their supply.

“The Goodwill in my very small town gets thousands of items on a daily basis,” Luna, a Depop seller who goes by luvbxnny and asked for her last name to remain anonymous, said. “People are always getting rid of things, so I don’t see an issue in anyone shopping at a thrift store.”

Other stores have experienced surges in donations as well. There seems no shortage of clothes finding their way into thrift stores. Moreover, thrift shop inventory consists of donations, meaning it costs them nothing to supply products. Thrifting minimizes waste rather than diminishing the supply.

The same can’t be said for much of the current fashion system and production. Many businesses in the industry use manufacturing methods that are extremely harmful to the environment and produce cheap, short-lasting clothes that are often thrown out.

“The current fashion system uses high volumes of non-renewable resources, including petroleum, extracted to produce clothes that are often used only for a short period of time, after which the materials are largely lost to landfill or incineration,” Chetna Prajapati, a lecturer in textiles within the creative arts at Loughborough University, said. “This system puts pressure on valuable resources such as water, pollutes the environment, and degrades ecosystems in addition to creating societal impacts on a global scale.”

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, in 2018, over 11 million tons of clothing and footwear were sent to landfills. 84% of unwanted clothes in the U.S. were incinerated or sent to landfills, and of the clothes in thrift stores, a 2018 Savers report concluded only 7% of the 3001 people surveyed purchase used clothing.

Thrifting combats this by preventing resources invested in making clothes from being used in vain. This is hugely beneficial as it lowers the massive amounts of clothes sent to landfills, which debilitate the environment. Thrifting is a sustainable alternative to minimize personal contribution to clothing waste and non-ethical fashion sources.

In recent years, a positive light has shed on thrifting, but the rise in popularity has been a cause of concern for many. They argue that prices are rising due to the increased influx of people thrift stores witness.

But even if the demand has increased, thrift shop supply is virtually inexhaustible and free. This undermines the theory of supply-and-demand and, by extension, any evidence for the argument of raised prices.

Waste is extremely prevalent in the clothing industry, especially in fast fashion. Many well-loved brands use cheap production, getting labor from workforces with meager pay and little to no benefits. Manufacturers specifically seek out labor from places where employees will have fewer rights and will be less likely to strike or call for better treatment.

Holding a high-level management position in fast fashion stores like Rue21 or Cotton On allowed Luna to see what really went on behind closed doors.

“I was able to see the raw data at Cotton On, and I knew how much my company paid for everything,” Luna said. “Most things only cost $1 or less, and they marked it up to insane prices. Meanwhile, I’m only making $12 an hour to run the store 100% by myself with no staff to help me.”

It reaffirmed her belief that thrift stores are a better alternative to supporting fast fashion and unethical corporations.

“At least when buying from thrift stores, you are supporting the people working there and their families, and depending on the thrift store you go to, the proceeds are going to a charitable place,” Luna said.

Thrifting, in any form, is unmeasurably better than supporting big corporations and fast fashion. It’s also a more sustainable, accessible option for people who are unable to afford slow fashion. By providing business to thrift stores, customers are also more often supporting ethical or even family businesses in some cases. Stores like Goodwill and Salvation Army give portions of profits to charities or are non-profit.

Giving back to the community and donating profits is a significant way that thrift shops help low-income people, as thrift stores aren’t always an option for lower-income people. Goodwill prices are often out of range for them, and they instead rely on free clothing drives, hand-me-downs, and donations.

“For the most part, I would classify this as a classist myth rather than a reality,” Leah Wise, a blogger and former thrift shop manager, said. “By that, I mean that middle and upper-class people have created this dichotomy as an exercise of their own guilt rather than based on any knowledge of the industry.”

Thrifting is a good option for everybody, regardless of income or societal standards. Arguments against thrifting are founded without much justification; it’s a much more complex issue in reality.

“The secondhand economy’s woes are often symptomatic of much larger issues, and I think it’s worthwhile to trace these issues back to their roots,” Wise said.