The modern world revolves around technology, but not everyone has the same access to it.

This digital divide grew more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as students require direct access to Wi-Fi to learn. In response to the need, the San Mateo County (SMC) expanded their public Wi-Fi to increase digital equity in underserved regions through their Digital Inclusion Initiative.

“We’ve realized, two or three years ago, that we could help cities and school districts to bridge the digital divide,” David Canepa said. “Through Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding, we’re able to get millions of dollars to help people through connectivity, whether it’s by setting up hot spots or providing technology and Wi-Fi equipment. We firmly believe that the new pencil and pens are now internet connectivity, and we are making sure that we get it to the right people.”

Canepa is the president of the SMC Board of Supervisors and represents District Five, which includes Brisbane, Broadmoor, Colma, Daly City, and parts of San Bruno and South San Francisco. However, the Board has come to realize that not all regions in the county are equal.

“We [SMC] are one of the wealthiest counties in the United States. That being said, some areas aren’t like Belmont or San Carlos. My district is pretty much ground zero, as well as East Palo Alto,” Canepa said. “I think we’ve done a good job to identify those communities first, prioritize those communities, and then try to deal with everything else secondary.”

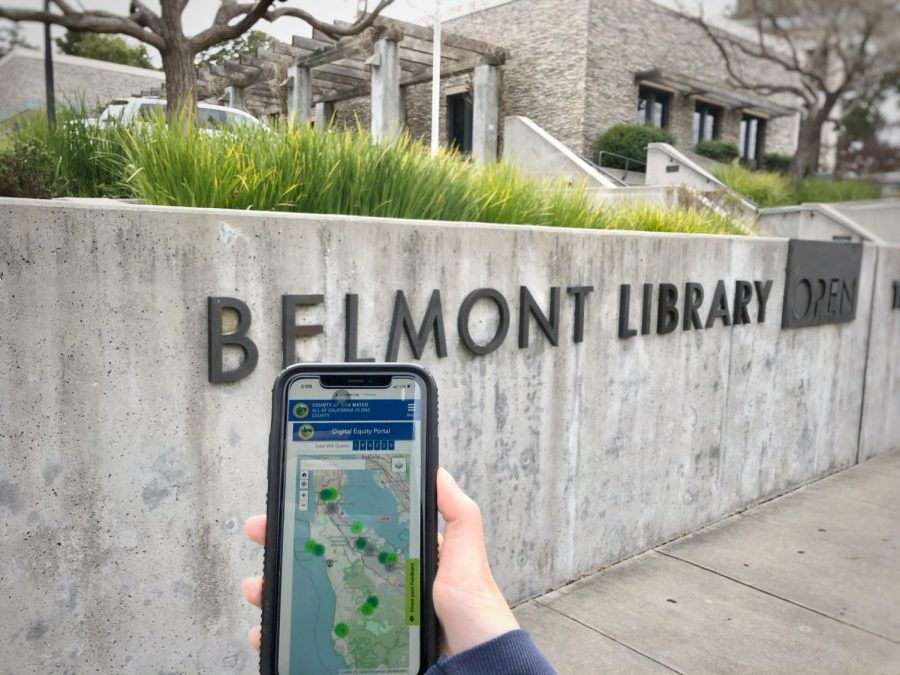

The county has added 230 more public Wi-Fi access points to address community needs and extended the public Wi-Fi networks to work at 12 of the peninsula library systems in the past six months.

SMC’s public Wi-Fi projects were funded with money from the CARES Act, a $2 trillion federal grant to support groups impacted by the pandemic, including individuals, businesses, and local governments.

Because the county budgets their money ahead of time — based on their fiscal year that starts in July and ends in June the following calendar year — they had already allocated most of their funds to different projects. As the overseer of the county’s technology department, Chief Information Officer Jon Walton is in charge of collecting money to provide Wi-Fi and technology for staff and citizens.

“We’d already started spending all of our money on things that we typically spend it on, like healthcare, roads, and public safety,” Walton said. “When the pandemic hit, we didn’t have a lot of extra money to solve the problem for internet access and public Wi-Fi, so the CARES money gave us those extra funds we needed to do this project. If we hadn’t had the CARES money, we probably wouldn’t be able to do nearly as much as we did.”

SMC has spent $6.3 million of the federal money helping people in underserved communities gain access to Wi-Fi. Other funds from the grant provided for food, housing, and purchasing hotels for homeless people.

One of the newest innovations the county has launched to expand public Wi-Fi is the Digital Equity Portal, an interactive map that displays all their Wi-Fi sites. Inspired by Google Maps, SMC created the portal to help those who need to find internet access.

“People can go to this portal and be able to search for a public Wi-Fi access point that is near to them, and then get directions on how to get there. The portal also tells people what the status of the network is, and there’s a link where you can request assistance as well,” Walton said. “It lets us see where people are going and where they’re using Wi-Fi, which helps us figure out where we might want to add more sites in the future.”

The enhanced map also shows just how large the county is.

“The county is really big, almost 600 square miles, and a Wi-Fi hot spot actually doesn’t cover that big of an area, maybe only a 500 feet radius circle. If you think about how big the county is, there’s never going to be enough devices to blanket the entire county with free public Wi-Fi,” Walton said.

To fight geographical disadvantages, SMC developed the Park and Connect program. Access points were placed in parking lots so that families and students can drive there and work in their cars.

“In areas of the county where there weren’t buildings we could put Wi-Fi access points on or there weren’t streetlights, we found places that had a nice big parking lot that’s well lit and central to everyone to access, and we placed really good Wi-Fi that covers that entire parking lot,” Walton said. “It’s probably not perfect; I wish people didn’t have to drive to where the access points were and that they could just work in their homes, but we just didn’t have enough time and money to make that happen.”

To ensure that they did not waste their funds, the county thoroughly analyzed each area’s needs.

“In order to pick out where we wanted to do the Park and Connect program, we did a lot of analysis of the census by looking at areas where kids got free school lunches to make sure we were placing all the Wi-Fi in the right places,” District Two Supervisor Carole Groom said.

Through the county’s survey, libraries appeared to be popular locations to access public Wi-Fi and information.

“The pandemic has really just shown how important library services are, and it has highlighted the importance of digital equity and equitable access to information,” said Danae Ramirez, the San Mateo County Libraries (SMCL) Deputy Director. “Libraries have always been supporters and encouragers of information and provided lots of mechanisms for our patrons to get information. During the pandemic, we really scaled up, and we were able to expand our services and provide significant access to people that otherwise would not have been able to connect.”

SMCL placed wireless access points at all 13 of their library locations, allowing people to work right outside of their buildings. People are also able to check out computers and hot spots. With the county’s help, the SMCL increased their hot spot availability from 750 hot spots to over 1,500 and purchased 250 Chromebooks for the community to use.

“Libraries have evolved over the years; they are much more digital now than they ever were,” Groom said. “In our libraries in San Mateo County, you can check out a laptop and a hot spot. For seniors who can’t really get out of the house very much, they can check out books on their computer, and then we deliver them to their curb.”

Students have experienced the many benefits of having access to technology and Wi-Fi in libraries, even before the pandemic.

“When I didn’t have my driver’s license yet, and I didn’t want to take the bus home, I would do homework at the library and wait to get picked up,” said Samantha Turtle, a senior and user of the library’s free hot spot service. “The library is usually near schools, so it’s easy to access for kids.”

The implementation and convenience of Wi-Fi at libraries are due to the rise in technology use in schools.

“Everything is getting digitized. Wi-Fi lets you stay connected to the internet, and you need to be connected to the internet if that’s where all your assignments are,” Turtle said. “I can’t remember turning in actual assignments other than projects.”

Turning in assignments online is not the only part of education technology has changed. In fact, learning itself is being digitized.

“Connectivity and communication are the two things that are the most important now. There’s so much to learn on the internet, especially if you have the Wi-Fi capabilities to get deep into something,” Groom said. “A lot of people now read solely on their computers, too. One thing I’ve really worked hard here while on the City Council is getting families to the libraries and reading together.”

Now that students have to learn in online classrooms, the need to support students who might fall behind due to a lack of internet access becomes even more critical, motivating libraries to work with SMC to provide access to technology and information.

“The county is working on many fronts to close the digital divide. Libraries partnered with the county early on and participated in meetings and discussions about the need in the community for internet access,” Ramirez said. “We looked for opportunities where we could help to fill gaps, and because we already offered Wi-Fi hot spots to the community, it was a natural partnership.”

To prevent the digital divide from widening during the pandemic, SMC partnered with the community, developing projects to help everyone gain access to the internet, especially those living in lower-income neighborhoods.

“We’re trying to flatten and eliminate the digital divide,” Canepa said. The only way we’re going to be able to do that is to make sure that whether you live in Atherton or Belmont, those same opportunities are given to kids who live in East Palo Alto or Daly City. That’s equity.”

The digital divide only adds to other inequities in the world. This problem, however, has only risen in recent years, and it comes from the expectation of having Wi-Fi.

“In the last five to 10 years, everything’s gone online,” Walton said. “The demand for the internet has shifted where people no longer see the internet as ‘Oh, that would be nice if I could access that.’ Instead, it’s ‘Oh, I don’t have access to the internet, and I can’t attend class,’ and that’s a real problem.”